During the Christmas holidays, for research and teaching reasons, I watched again a number of Italian films from the 1910s, in particular, those films that are grouped under the genre of diva-film. This is a heterogeneous genre, but one thing these films have in common is the strong presence of the female lead. Or the diva, to be precise, legendary names such as Lyda Borelli (1887-1959), Pina Menechelli (1890-1981), Francesca Bertini (1892-1985) and others. The films are for the most part melodramas and, in some cases, the woman is a femme fatale who is often punished at the end; in other cases, the films draw to a happy ending story like Sangue Bleu (1914) directed by Nino Oxilia (1889-1917), starring Francesca Bertini.

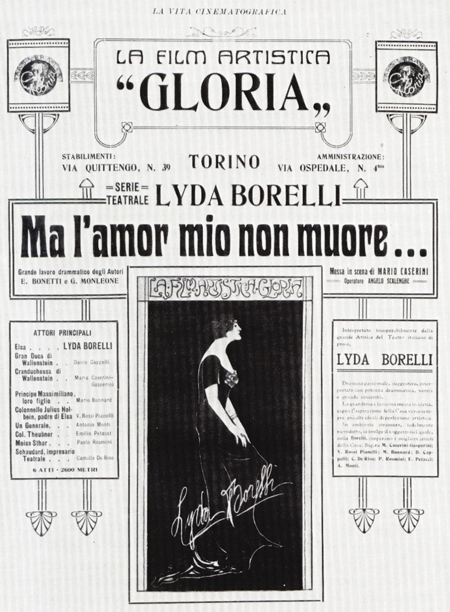

The film Ma l’ amore mio non muore! (1913) directed by Mario Caserini (1874-1920) for the Turin production house Gloria gave Lyda Borelli, who plays Elsa the protagonist of the film, a profile as a film actor. Before this film, she was already very famous to the wide public thanks to her stage career, above all in the role of Salomè. In fact, in L’amore mio non muore, a love and espionage story, Elsa is exiled to Switzerland, where she becomes a stage actor who reaches great fame and popularity. As Borelli did in real life, we see Elsa dressed as Salomè on and off stage, with her very long blond hair, a dreaming gaze like that of the beauties depicted by pre-Raphaelite painters and a body whose gestures speak a language that is at the same time unique and universal. The great Italian diva, with L’amore mio non muore, marks the beginning of a new film genre―the melodrama–that will have an enormous national and international success. The film also marks the beginning of the film career of Lyda Borelli. Not being able to use words as she did on stage, she , holds and fills the frame with her body, her sinuous movements, the great expressivity of her eyes and her elegant, sophisticated and memorable costumes. Antonio Gramsci described Borelli as “the artist par excellence of film in whom language is the human body in its ever self-renewing plasticity.”. But it is the nuances, the ethereal and sensual beauty of the actress that act as the most important medium of a film that continuously changes.

The film Ma l’ amore mio non muore! (1913) directed by Mario Caserini (1874-1920) for the Turin production house Gloria gave Lyda Borelli, who plays Elsa the protagonist of the film, a profile as a film actor. Before this film, she was already very famous to the wide public thanks to her stage career, above all in the role of Salomè. In fact, in L’amore mio non muore, a love and espionage story, Elsa is exiled to Switzerland, where she becomes a stage actor who reaches great fame and popularity. As Borelli did in real life, we see Elsa dressed as Salomè on and off stage, with her very long blond hair, a dreaming gaze like that of the beauties depicted by pre-Raphaelite painters and a body whose gestures speak a language that is at the same time unique and universal. The great Italian diva, with L’amore mio non muore, marks the beginning of a new film genre―the melodrama–that will have an enormous national and international success. The film also marks the beginning of the film career of Lyda Borelli. Not being able to use words as she did on stage, she , holds and fills the frame with her body, her sinuous movements, the great expressivity of her eyes and her elegant, sophisticated and memorable costumes. Antonio Gramsci described Borelli as “the artist par excellence of film in whom language is the human body in its ever self-renewing plasticity.”. But it is the nuances, the ethereal and sensual beauty of the actress that act as the most important medium of a film that continuously changes.

Cinema then was a new art form and technology that had revolutionized the vision and perception of the world and reality. The shift from the stage to the cinematic marks a passage to a new state where the diva condensates and carries the cinematic form and its emotions. The game of transparencies and veils that move and shift in the wind create a specifically cinematic effect as Borelli comes forward in a scene or as does the mirror that is prominent in a scene in Elsa/Lyda’s dressing room. Here we see a three paneled mirror that frames her figure and multiplies her persona as she mirrors herself and plays a game with the camera; we see how she is framed from the back, then the front, giving a montage effect.

Lyda Borelli in a picture by Mario Nunes Vais

A diva such as Borelli legitimizes not only the work of the artist and the actor, but also legitimizes cinema as art. In a historical period in which the avant-garde movements in painting and literature started to question the role of the artist, cinema and the diva film in particular, seem instead to take a different path through the dominating presence of the female actor. The diva film, then, legitimizes the female actor as the artist. Cinema makes a pact with the devil. And we see plenty of little devils, ghosts and magic in the cinematic experiments of the opening years of the 20th century in short films; lasting 8 or 10 minutes that the film historian and critic Tom Gunning has called “cinema of attraction.”

The diva film seems to continue this kind of spectacle and transforms modernity itself into a spectacle thanks to the presence of actors like Lyda Borelli. She was so fashionable at that time that young women imitated her as they imitated movie stars as their idols. Young women modeled their looks, gestures, clothing and hair on Borelli to the point that a neologism was coined to synthetize their behavior: borellismo. The postcards, of which hundreds were produced, the periodicals, the publicity of production houses and films then were like the Twitter and Instagram of today. The divas and the diva film materialized the desires and projections of their fans and bolstered popular culture.

Rapsodia Satanica

But the film that was the great masterpiece, and which again featured Lyda Borelli as a protagonist, made by the Turin born Nino Oxilia, was Rapsodia Satanica (1915). In this film, an elderly noblewoman makes a pact with the devil to regain her youth provided that she does not fall in love. Predictably, her dream of eternal youth does not come true and the protagonist succumbs to the inexorable passing of time. Nino Oxilia (1889-1917) was a poet, journalist and dramatist who directed many successful films, including the already mentioned Sangue Bleu. In these films, painting and photography seem to interact with the work of the camera in a process that has been defined as intermediality. There are certain scenes in Rapsodia Satanica that resemble paintings by Klimt. In fact, some of the photograms were tinted with a stencil technique, a first for film at that time. With their beauty, these films express a great fragility that lives side by side with a period of great social, political and scientific transformations, and war. It was also a period that saw for the first time Europe devastated by a world war that will upset all sense of order and certainty. Oxilia, in fact, who was a master at expressing and representing the fleetingness of time and youth, fought in that war, but would not come back from the front. In 1917, he was tragically killed by an Austrian hand-grenade. A hundred years on from these films and the outbreak of WWI, revisiting them could make us aware of new ways and frameworks within which to interpret Italian and European history at the beginning of the 20th century.