The piazza has been and will always be the nucleus of urban life. In Italy, Luigi Piccinato, one of the forefathers of city planning, teaches that the piazza is "an aesthetic and perspectival episode, a kind of reception room for the city". The italian piazzas of the renaissance have a strong geometric quality, as though the forms were overlayed onto the existing urban fabric to carve specific areas into urban living rooms for daily encounters. Such concepts were never formally translated on the other side of the Atlantic. In fact, the piazza is a concept that is far from American. However, closer observation of Manhattan's map brings us to an exception: the Lincoln Center.

Delimited by West 62nd Street, West 66th, Columbus, and Amsterdam avenues, the plaza of the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts was realized between 1962 and 1968 and owes its name to the small area between Broadway and Columbus Avenue defined by New Yorkers as a "piazza" and entitled Lincoln Square. From Columbus Avenue, we can see the square from its most suggestive angle: elevated from street level, it appears as an island of monumental buildings, rigorously clad in travertine. Access to the square is from a beautiful stair that seems to inspire a time separation: these few steps act as a “time passage” for the visitor who, from the chaos of the city, emerges in a kind of isolated citadel with Renaissance characteristics. A space significantly different that could be considered abnormal for this city.

Piazza del Campidoglio, Rome

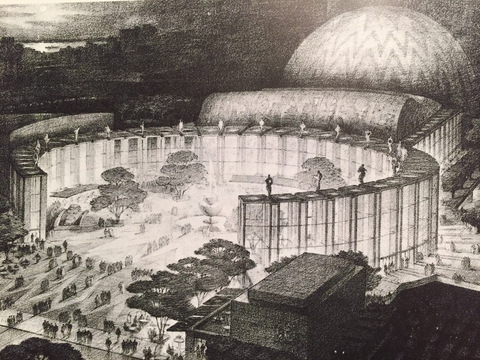

Lincoln Center is a sort of sanctuary of the arts, a testament to the capacity of mankind to imagine and represent an ideal world of beauty and harmony. The creation of this place, with its graciously proportioned outdoor atrium, impacted the nature of the whole neighborhood which underwent significant changes and was consequently revitalized. Its construction underwent various phases. Inspired by Bernini's San Pietro, one of the first proposals envisioned a building rising around a circular piazza, but several modifications brought the design to its definitive plan as seen today. This is clearly inspired by another masterpiece: the Piazza del Campidoglio in Rome by Michelangelo. The motivation behind this reference can be found in the story of Wallace K. Harrison, creator of the Masterplan and one of the three buildings: the Metropolitan Opera House.

At this point, Harrison, young architect and private consultant to the Rockefeller family, had already worked on notable buildings in the city. At a very young age, he took part in the creation of the Rockefeller center, built the terminal of La Guardia airport, worked on the rethinking of Battery Park and was also chosen to lead the team of international architects who would design the new seat of the United Nations, the "glass palace", for which he selected the schemes of Le Corbusier and Niemeyer amongst various proposals. Wallace Harrison was trained at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts of Paris and received the Rotch Traveling Scholarship in 1922, a remarkable opportunity to go on a Grand Tour across Europe, allowing him to fulfill his strong desire to spend a period of his life living in Rome, where he studied ruins from Michelangelo's amazing masterpieces. It was this sojourn that left in Harrison and indelible impression that would inspire him in later years.

One of the first drafts for the Lincoln Center

Some of the prominent figures involved in the construction of the Lincoln Center. L-R: Edward Mathews (SOM), Philip Johnson, Joseph Mielziner, Wallace Harrison, John D. Rockfeller III, Eero Saarinen, Gordon Bunshaft, Max Abramovitz, Pietro Belluschi

Upon his return to America, he embarked upon a brilliant career while harvesting, for many years, the dream of being the first to design a modern theatre for the opera of New York. Finally in 1955 Robert Moses hired him for the creation of the Metropolitan Opera House; the architect accepted with enthusiasm. Influenced by his roman experiences, Harrison proposed a masterplan for the Lincoln Center that, like the Campidoglio in Rome, acts like a large urban stage. After years of development, the result was an extraordinary architectural event for the city, a sort of merging between the spirit of the Campidoglio and that of Eur; and all this a few blocks from Central Park.

Other reknowned architects contributed to the success of the project, each of whom designed a building. Max Abramovitz designed Avert Fisher Hall, Piero Belluschi the Julliard School, recently expanded with by Diller + Scofidio and FxFowle, Eero Saarinen the Vivian Beaumont Theatre, and lastly, one of the pioneers of post-modern architecture Philip Johnson, the New York State Theatre- a central building to the whole masterplan which was also rooted in Roman inspirations. Johnson loved the buildings of the E42 and clearly monumentalized the construction detail wrapping it in travertine such that, so typical to Johnson, the Campidoglio confronts the Eur on the streets of the Upper West Side.

Despite the strong and undeniable roman influences, the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts is one of the greatest symbols of American architecture of the 60s, designed by the founding fathers of the modern movement. It's interesting to rediscover that, once again, modern gestures are linked to history and that only through the reinterpretation of the past we continue to develop winning solutions for the contemporary city.

Traduzione dall'italiano di Christine Djerrahian.