In 1969, with the help of old money, my mother and father Piera and Gesualdo bought a house in Coney Island, two blocks from the boardwalk and the Atlantic Ocean. Like many houses in the run down neighborhoods of Brooklyn, it was very plain outside, with cheap tar shingles in the front and old aluminum siding sides, weathered the way things by the ocean are weathered, bleached and sanded by the wind. The tall three-story house was, as the real estate ads say, “semi-detached,” and a good thing, too. It pitched slightly to the right, like a clipper ship in a painting.

I remember the day we arrived, November 11, 1971. I pushed open the creaking door of our station wagon. It sounded like a vault opening in an old horror movie. It was New York City winter the way winters used to be. I felt wet snowflakes on my ears and eyelashes. My eyes stung as we trudged to the front door of the house. Back in Sicily, Gesualdo had once heard of Coney Island, probably seeing it in one of those retouched postcards, and so, after sojourns in the immigrant Italian enclaves of Camden and Brooklyn, he brought us to this tough and colorful neighborhood. The roomy, rickety house with the huge yard took on the feeling of a headquarters, a fort, a hideout, a court, a prison, the scene of many screaming matches, beatings, dreamy days with my books, lovely moments with my friend Tom Riley, crazed games in the street with the droves of kids, lots of good, rustic food, and a long line of shell-shocked relatives just arrived from the old country.

Our apartment was a row of five huge rooms. First was the gloomy, wood-paneled living room. The three windows facing the street were hung with my mom’s idea of beautiful curtains, heavy, ivory colored cloth with huge, lime green, embroidered flowers. These curtains succeeded in blocking out the blue-white glare of the Atlantic sunlight. Like kitchens of the old village folks I got to know in the “old country,” it was murky and dark, and much furniture was placed in this large space, two couches, a deep armchair, a large oak TV console, and in the corner behind a partition, a small bed tucked into the corner where I sometimes slept and talked to the secret pet turtle I kept under the bed in a bowl of skuzzy water. Next was the kitchen, with a table that could seat 12 and cupboards and shelves enough for a small restaurant. This is where my grandmother Leonilda Messore DiMambro would roll out a huge thin sheet of yellowish dough and cut long tagliatelle (literally, “cut things”) by hand. A door on the side went out to the yard. Another door led to three bedrooms you walked through until you reached the brightly lit back room with its own door to a large garden. My grandfather Domenico DiMambro worked that garden, and we had more tomatoes, zucchini, peppers and string beans than a little kid would ever want to eat. My brother and I used to dig in the dirt there and would come up with relics of Coney Island, old beer bottles from the 1930s, combs, rancid leather change purses that still clicked, and moldy bouquets of newspapers. To the side of the garden were three capacious “shindies,” as my father called them, probably having heard someone say “shanties.” These were made of cinder blocks. The first two were already there when we moved in and full of cans of paint, plaster, and tools. The last one my father built himself out of beautiful, porous white blocks. He was a housepainter and a handyman of sorts. He never painted that last shindy. Such were the habitats available to laboring families if you were willing to live in a slum one hour away from “the city” by subway.

The air of Coney Island is thin and clean, and sound carries far. At noon there was the air raid siren, so loud you couldn’t think. At night, you could hear the subway trains as they rounded the curves on their way to the last stop, Stillwell Avenue, making long, steely wails and shrieks. In the late summer you could hear bongo drums from the beach and wafts of screams from Steeplechase and Astroland, the amusement parks by the boardwalk. My clever little brother memorized the cackle of a robot gypsy mannequin in a glass box outside an arcade three blocks away. She was clothed in a tight green vest and faded linen, a replica of an idea of a Gypsy (There were groups of actual gypsies living in some of the large houses on Mermaid Avenue.) When someone put a nickel in the machine she would swivel on her bearings, lurch down, pick up a tiny card with her plaster hands, and drop it in the chute. Then the maniacal cackle would start up again, a stanza of laughter of about six lines, the last one sounding like a squeaky shopping cart coming to a stop. If I’m not careful, this laugh will stick in my head even now and it will take a few days to fade. In the winter, when the crowds were gone and the air was crisp, there was the sound of the wind through the roller coasters and the already ancient Wonder Wheel, and a long, low, mournful flute-like sound that we couldn’t figure out at first. Of course my clever brother did figure it out. He had noticed that the Astro Tower, a very high steel pillar with a rotating observation deck, had a large oval opening near the top. We used to go by there on winter nights, when no one was on the boardwalk and the Atlantic Ocean was a dark, cold, dark, creamy mass. The wind blew in from over the water and we stood there and listened. Long live my clever brother.

We were on West 15th Street, between Neptune and Mermaid Avenues. The whimsical place names in Coney Island did not match the spirit of my neighborhood. Brooklyn was the land of street games and street crafts, but also street law, whose deep rules we learned only as kids can learn. We well understood the dire penalties of ignorance, and of not finding a group or subgroup to belong to, so that you could be shielded by the random violence everywhere. Children of all ages joined gangs, and Coney Island had a gang for everyone, the 16th-Street Boys (Italian-Americans), the Danbees (from my block, Italian, black, and Irish), Homicide Inc. (Puerto Ricans), Black Pearls (African-Americans), the Homicide Juniors, and the Girl Homicides. Very few of the gang members were truly “homicidal,” but you still had to be cautious walking out beyond your own block. Once, I was surrounded by some Homicide Juniors, about 15 kids from 6 to 10 years old who tore at my clothes and backpack until I was picked clean. I was at Playland, a huge arcade, on a crowded Saturday afternoon, and not a single adult raised a finger to help – New York City in the 70s.

The biggest kid on the block was Rick. He sought out the younger, gentler kids, like skinny Irish Paul, whom he sent to the hospital for a month with a deep gash to the side of the head. Rick had been jealous of Paul’s shoeshine box. Paul would go to the boardwalk and make money. Ah, that was the dream, to work, to make money. But Paul made the mistake of telling us how much money he made. This brought on some feelings. One day, Rick tore the box out of his hands, pushed him hard to floor, and while Paul was sitting on the street crying, Rick smashed the metal shoe pedestal onto Paul’s skull. The ambulance came and took him away and we didn’t see him for weeks. While Paul was in the hospital, Rick shattered and burned that shoeshine box in one of the empty lots on our block.

Because I was one of the immigrant kids and much younger than Rick, he often turned his sadistic attention to me. My accent was disappearing, but anything that made you different evoked teasing and bullying, and possibly a full-scale street beating. I was especially vulnerable when I was coming home from school. There was something about the way I carried my books that enraged him. Rick was one of those Italian-American guys with greased hair who would stash his notebook down the back side of his jeans on those rare occasions he went to school. We all watched John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever and Grease, and before that in the TV show Welcome Back Kotter, but for me there was nothing cool about that kind of cool. I never wore a tight white T-shirt with a pack of cigarettes jammed under the sleeve, like so many of the Irish and Italian kids did, even as young as eight, playing a role already laid out for them by American culture. For me, despite all the pressures and attacks, from the street or from the family, I was secure in what made me feel strong. I felt like a king when I read books, one after the other, and it was those books that eventually led me off the block. I held them together with a thick, ribbed rubber band and tucked them into the crook of my elbow as I walked, like girls did on TV. I knew it made me a target. I wasn’t so lost in The Hobbit or Dune or the nerdy revenge narratives of Spiderman that I couldn’t understand this. There were things worth fighting for, though. In my heart, I knew I had to eventually face all bullies, and if possible, defeat them. And this included people in my family.

When Rick was bored, he reverted to one of his favorite rituals of cruelty, whacking me on the shins with a stick as I tried to make down the block to my house.

“Dance!”

The only defensive strategy I knew, which I’d learned from facing down my father’s sudden rages, was to try to show no reaction to the stinging pain. Just as my father would calm down faster if I didn’t flinch under the burning whack of his belt strokes, so I hoped that Rick wouldn’t get any additional pleasure from his dance game. I’m not sure if this ever really worked, because Rick would pursue me down the block, and as long as he could get either some laughs or horrified stares from other kids, he would keep at it. He fed off their hunger for violence, their morbid desire to see what a victim could do, if anything. Sometimes, at night, I would survey my body and see bruises on my shins from Rick, or from Michael of the 16th-Street Boys, and matching bruises on my thighs, hips, and forearms from my father. Whether I was in the street or at home I could never let down my guard.

Fighting back against Rick, Michael, or against my father was unimaginable. Rick was a stocky, muscular teenager and my dad worked at manual trades, so their strength was immense. I was 11, scrawny, bookish, with a mop of curly black hair and ill-fitting pants always a size too big. Eventually, I managed to hold my own, but I didn’t realize my strength and resilience at first.

One day, I was on my way home and Rick was sitting on the low step in front of his front door. Today I had made it all the way down the block with no confrontation – a rare feat. All I had to do now was get past Rick and I’d be home. His place was the last one before my yard – just a few more steps! He had a stick in his hand, as usual, and there was a puddle of dirty water near his feet. Rick was lazily swirling that water with the stick, when he saw me coming by. He decided he would splash some on my pants. Classic Rick. My instinct was to run. My instinct was almost always to run. This time, though, I decided I was tired of the badgering, and wanted to do something definite, something to squash the fear, the anticipation I always felt around my tormentors. I thought of the dramatic possibilities now, all of which were terrifying. Rick was sitting on a low step, so his face was about even with my chest. I couldn’t believe what my mind was telling me to do. I walked towards him, reared back my arm and punched him in the face as hard as I could. This was an exhilarating moment and I thought it would be like on TV or in comic books, a game-ender. This was the iconic punch-in-the-face, the way all altercations were supposed to conclude.

Instead of being surprised, Rick eyed me calmly. He snickered. He actually loved this moment because now he had complete license to beat me bloody. Before he arose, though, I hastily reached back and punched him again. Maybe that would do it. Again, nothing. Again, he just smiled. I have to say, despite what happened next, there was something delicious in the percussion of my knuckles on his fleshy face. I had so rarely in my street life had the chance to truly punch a person right in the face. Rick’s smile was creepy, and his glistening green eyes maniacal. He got up slowly, and as I backed away he took two long, loping steps and stood in front of me. My back was to a car, and my front door a few feet away, past our garage gate, but I didn’t run. I didn’t want to run. I was shocked and mesmerized by the power of this moment, and was still defiant in the face of pure fear. The air was thin and still, the air of the Island. The ground we stood on, our arena, was hard concrete, cracked in places, with embedded pebbles and bits of glinting granite. This was our stage, our Coney Island, where I’d witnessed kids (and adults) fight their way to sometimes horrible conclusions.

Rick began methodically, and I remember this in slow motion under that white coastal sun, little stars floating off to the edge of my vision like shimmering flies. First he punched me hard in the stomach with a left uppercut. When I instinctively doubled over, he pulled my head down with his right hand and led my face into his knee. I felt a hotness between my eyes and got dizzy, the roofs of the houses across the street dipped like ships in a storm. I fell back and to the side. He began a series of slow, powerful blows, first to the back of my head, and then between my eyes, and on and on. Whenever I got too low to the ground, he’d kick me up and punch me some more. His technique was utterly logical, and devastating. As a chess player I understood this, and was horrified – just knowing how strategic he was was almost more painful than the blows themselves. It offended my intellectual vanity, because dumb Rick was smarter than me at something. How utterly humiliating – but for the first time I began to see that he was actually very skilled at something.

At one point, I found our two cheeks right next to each other, his smooth and hot, almost lovely, mine streaked with snot and blood. I was breathing hard, saliva dripping in long lines, tears popping out of my eyes, but I still found enough focus, and ferocity, to turn on his soft face. I took a bite. With desperate, mindless strength, my teeth sunk deeper and deeper, gripping and slightly tearing, and as I fell downward, I pulled his skull down with me, and felt it thunk on the ground. In a dark flash he was gone, running into his house, bleeding from his cheek, yelling, “Ma! Ma!” There was blood trailing over the sidewalk, on his front step, and spattered on the bottom of the white wooden door. I viewed the carnage. I didn’t feel triumphant. I felt a profound sorrow. I ran home.

Soon our two tribes came streaming out onto the sidewalk, mostly women. At this time of the day, the men were either sitting in their shaded gardens, already drunk, at work, or simply gone. At different points in my life, my dad was all of the above. The two brigades faced each other. On their side, second- and third-generation Italian-Americans, flowery house dresses, hair rollers, furry white slippers, and face cream, and on ours, old country apparel, modest dark-colored skirts over the knee, white aprons, headscarves, and dusty black shoes. Even the body types were different. They were taller, fleshier, lighter skinned – from watching too much TV my mother used to say. Our team was shorter, stockier, darker, and more sinewy. There were about 15 women on each side. There were older sisters, grandmothers, moms and aunts, some breathless kids, and in my case, a couple of kinky-haired cousins from Sicily.

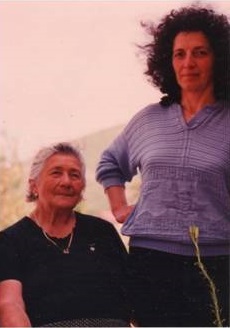

My grandmother stood in front. She was wearing the dark blue canvas skirt of the Vallemaio women. Her shins were tan, full, shiny. She was about as tall as I was, something around 5 feet high, with fleshy shoulders and small powerful hands. She had freckles and her salt and pepper hair was arranged under the small, triangular florid headscarf. I couldn’t see her eyes, but I knew how arresting they were, jade green with little brown flecks.

Such was Leonilda, in her fifties, having lived a whole life in a small mountain village, having followed her husband unwillingly to this strange place, l’ameriga, standing in my defense. I was inspired and awed. I knew she hated Coney Island, brucolino, and America, with its inexplicable rudeness delivered in an indecipherable language, its oversalted, sugary food, with its gangs and creeps all over the streets, and that infernally dirty and dangerous subway. I knew she managed here by staying out of the way, by cooking, by baking, by going to the beach with her short, squat, loud friends, and by praying endlessly to the gaudily retouched saints on her little cards with the gold tassels. In the context of Coney Island street life, she was a kind and retiring woman. But there she was, as ghetto as the best of them, squaring off, arms crossed on her chest. My heart beat with pride, and with worry for her safety.

The shouting began. On our side, dialect Italian, what the hell is this? – ma che gaspita? what kind of animals allow a little boy to be beaten so severely? – bestie! where is your honor? vigliacchi (cowards) go inside and fix your hair, lazy amerigani on welfare! On their side, “go back to your country!” “guineas!” “learn English!” “stupid immigrants!” I was surprised by this. There we were, all Italians, no? So this is what it was to be American, this elusive sought after identity? to be able to look down on people from your own country? I looked at Rick’s tribe and wondered, “will that be us soon?” I actually really liked some of them, who, on other days would teach me games, crafts, cooking, English. But now we were down to it, a huge street drama, and I knew what side I was on.

Amidst all the yelling, one voice that no one in the neighborhood heard very much gradually became audible, that of my grandmother. There was a small interval of silence. She stepped into the space between the afternoon armies, slammed a foot on the ground and yelled, hoarsely, “Facka You!” I thought, proudly, ah hah, so she did speak English after all! This was one of the most glorious moments of my childhood. It was too funny, too extreme, and coming from the short, vigorous, lovable woman with her headscarf, what could you say after that? After a moment, everyone started talking again, but simmering down. We filtered back into our homes, muttering, as we often did, about this curious illogical place, l’ameriga, but for once, English was neat, eloquent, and highly comprehensible. As for me, I saw that the balance of power was now restored. Soon the adults would start speaking to each other again, because in those days, neighborhood life was mostly outdoors, and we needed each other in so many ways. More than ever, I looked forward to my visitations with the kind old spirits of Coney Island, the widows and carnies I’ll tell you about, and to the street games with my friends up the block.