“Human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear” is stated on the first page of the Preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was released on December 10th, 1948. Article 19 states that “everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.” Yet, today, on the 26th annual World Press Freedom Day, the collective message among panelists and UN officials alike is one of utmost concern for the preservation of these principles across the world.

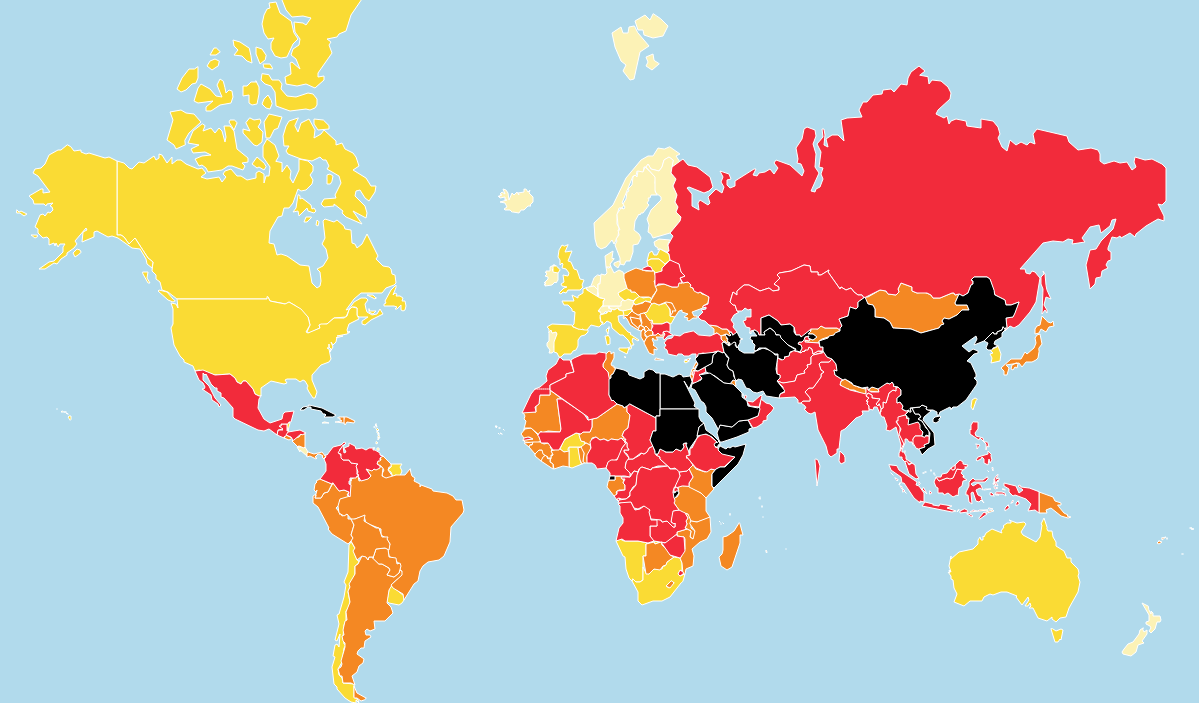

The event, Media for Democracy: Journalism and Elections in Times of Disinformation, began with a welcome message and introduction by H.E. Ms. María Fernanda Espinosa Garcés, President of the UN General Assembly, who stated “with a heavy heart” that “last year, the UNESCO Conservatory reported the murder of 99 journalists. Hundreds of media workers have been intimidated or imprisoned. Reporters Without Borders (RSF) chose to give its 2019 World Press Freedom Index the title ‘[A] Cycle of Fear’—that doesn’t give us great hope.” This opening sentiment covers the array of stages involving the deterioration of freedoms of the press internationally. It’s better in some, like in the Scandinavian countries (which routinely rank in the top places of press freedom), and worse in others, like Middle Eastern countries (which routinely rank among those at the bottom of this list).

Ms. Alison Smale, UN Under-Secretary-General for Global Communications, echoed Espinosa Garcés’ disheartened attitude towards the current situation; the press is being undermined throughout the world because of the dissemination of misinformation, sometimes referred to as “fake news.” However, Smale stressed that, “the moniker ‘fake news’ has become a catchphrase to discredit journalists and the news stories they report on,” and that it “is a misnomer: if it’s fake, it cannot possibly be news.”

It is worth noting that the United States has fallen, in just two short years, from 43rd place to 48th place, from a yellow zone to an orange one on the RSF freedom color scale. It’s not difficult to see the connection between this and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Elections. J. Alex Tarquinio, President of the Society of Professional Journalists, admitted, “It strikes me as appropriate that we’re meeting today here in New York because the 2016 U.S. Presidential Campaign, which concluded with an all-New York finale, really was a wake-up call and it put the institutions that defend democracies around the world on high-alert.” Clearly, even the U.S., whose students pledge their allegiance on a daily basis to the country that stands for “liberty and justice for all,” has to be critiqued with respect to the way its officials treat journalists.

Mr. Antonio Guterres, Secretary-General of the UN, could not attend the event in person, however, he did impart a few words in a video presentation during the first panel, on the importance of the free press.

“No democracy is complete without access to transparent and reliable information,” he firmly stated, “It is the cornerstone for building fair and impartial institutions, holding leaders accountable, and speaking truth to power. And this is especially true during election seasons.” H.E. Fatima Kyari Mohammed, African Union Permanent Observer to the UN, underscored this idea when she asserted that, “…the institutions of a free and safe press are a substantive component of peaceful societies. It follows that a free and safe press must be able to access and disseminate information of public interest without attack.”

Perhaps the most impactful moment of the event was when Valeria Robecco, ANSA News Agency correspondent and President of the UN Correspondents Association (UNCA), read off the names of each journalist killed in 2018.

Abadullah Hananzai; Abdul Manan Arghand; Abdul Rahman Ismael Yassin; Abdullah al-Qadry; Abdullah Mire Hashi; Achyutananda Sahu; Ahmed Abu Hussein; Ahmed Azize; Aleksandr Rastorguyev; Ali Saleemi; Ángel Eduardo Gahona; Awil Dahir Salad; Bashar al-Attar; Carlos Domínguez Rodríguez; Chandan Tiwari; Gerald Fischman; Ghazi Rasooli; Hamoud al-Jnaid; Ibrahim al-Munjar; Jairo Sousa; Jamal Khashoggi; Ján Kuciak; Jefferson Pureza Lopes; John McNamara; Juan Javier Ortega Reyes; Kamel abu al-Walid; Kirill Radchenko; Leobardo Vázquez Atzin; Leslie Ann Pamela Montenegro del Real; Maharram Durrani; Mario Leonel Gómez Sánchez; Mohammad al-Qadasi; Mohammad Salim Angaar; Musa Abdul Kareem; Mustafa Salamah; Navin Nischal; Nowroz Ali Rajabi; Obeida abu Omar; Omar Ezzi Mohammad; Orkhan Dzhemal; Paúl Rivas Bravo; Raed Fares; Ramiz Ahmadi; Rob Hiaasen; Sabawoon Kakar; Saleem Talash; Samim Faramarz; Sandeep Sharma; Shah Marai; Shujaat Bukhari; Sohail Khan; Wendi Winters; Yar Mohammad Tokhi; Yaser Murtaja

At the end, she declared, “There is no more time for words, we need actions” because “journalism can be an extremely dangerous profession,” and hundreds of journalists worldwide were either missing, detained, or killed in 2018. Already in 2019, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, three journalists have been murdered and two have been killed in crossfire.

But, as Robecco later said, it’s not just physical danger that threatens journalists and democracies internationally. The U.S.’s current situation is a stark reminder of the way that technology has a certain level of power and capacity to distribute a volume of false information large enough to eclipse collective faith in the democracy of one’s own country. The threat artificial intelligence (AI) and social media pose to the bedrock of democracies across the world is very real and very dangerous. During the second segment of the event, Prof. Meredith Broussard, Associate Director of the Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute at NYU, elaborated further on the scope and intensity of involvement of AI in the political and social arena and what it means for electoral processes globally. Prof. Broussard introduced to the audience the idea of “techno-chauvinism,” which she defined as a bias that holds technological capacities as greater than human capacities. It is incredibly easy to allow technology to take over every aspect of our lives; social media provides connections to friends, family, job opportunities, and news (and I list this last item with several caveats and qualifications in mind).

There are definitely advantages to having what we have in terms of social media platforms—namely, that we can disseminate important information quickly. However, this implicit trust in the online media available to us is what leads to the increase in unwavering support of techno-chauvinist concepts. Prof. Broussard said, “The social media companies have given us this notion that, somehow, because they’re using algorithms to sort through content, it is…superior to human judgment, and that someday there’s going to be this grand world where the machines are going to autonomously determine what is good content and what is bad content and the social media platforms are going to work completely without human intervention.” This is not realistic. As Prof. Broussard explained, “we’ve tried this [attitude] and it hasn’t worked.” Misinformation circulated online caused the U.S. to drop five places in the World Press Freedom Index. We clearly needed human rather than Facebook intervention.

Stephen J. Adler, Editor-in-Chief for Reuters, introduced by Maher Nasser, Director of the Outreach Division for the Department of Global Communications, pointed out that this lack of human intervention has further disastrous impacts in other countries, as in the case of the genocide taking place in Myanmar against the Muslim Rohingya, where Facebook is utilized to spread hate speech and false information about the persecuted group. Myanmar’s own government is responsible for the diffusion of this hateful rhetoric. Journalists have been imprisoned for covering the atrocities committed against the Rohingya, much like in other countries where press freedom is severely limited. H.E. Amal Mudallali, Permanent Representative of Lebanon to the UN and Vice-Chair of the UN General Assembly Committee on Information, had said a bit earlier that at times “killing the messenger was the preferred way to get rid of the message,” and even if the degree to which this remains true might be up for debate, the fact that it still happens is certain (Saudi journalist Jamal Ahmad Khashoggi is one of several journalists intentionally murdered last year).

Additionally, regarding Myanmar’s current political situation, as is true for many other country-specific political landscapes across the globe, the fuel to the fire is whether or not people can access reliable information. Perceptions are formed and opinions are made with respect to political and social events based on what we believe to be true. This, of course is why protecting the rights and lives of journalists is so crucial. As Adler explained, “I think we in the media…help people get good information, so that they can make good decisions.” This, of course, was touched upon by Guterres, Espinosa Garcés, and other panelists earlier on in the event. H.E. Francois Delattre, Permanent Representative of France to the UN affirmed that “freedom of expression…is indispensable for good governance, democracy, free and fair electoral processes, and the accountability of governments.”

Yet, people are “only going to know if it’s good information or not if they have some media literacy skills,” so, beyond raising awareness through World Press Freedom Day, it is absolutely essential that the topic of misinformation and “fake news” is taught in classrooms to children of all ages. It’s what will make future generations active and accurately-informed citizens, empowering them to make the right political decisions for themselves. As Guterres said when he closed his video message, “Facts, not falsehoods, should guide people as they choose their representatives…When media workers are targeted, society as a whole pays [the] price.” Or, in other words stated by Warren Hoge, Senior Adviser for External Relations at the International Peace Institute and Former Editor and Foreign Correspondent of the New York Times: “post-truth is pre-fascism.”

To monitor the situation of the freedom of the press around the world, Reporters Without Borders and the Committee to Protect Journalists are two indispensable and reliable sources.