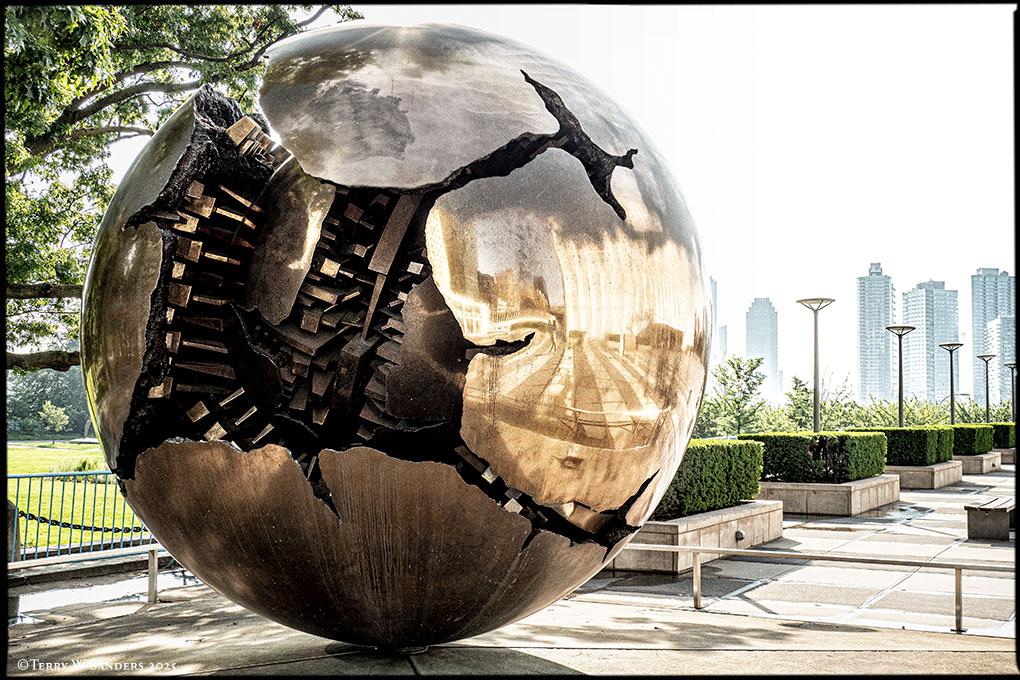

Between the East River and the fluttering banners that line the entrance of the United Nations headquarters, in the open expanse of the plaza that leads to the iconic building, stands a bronze sculpture whose fractured symmetry and enigmatic design have, for nearly three decades, captured the curiosity of passersby—from heads of state and diplomats to staffers and tourists alike. The piece, a massive sphere sliced by deliberate, jagged incisions that open onto an intricate interior of interlocking forms, appears at once like a mechanical core laid bare and a natural shell split open, suggesting not harmony or resolution, but the fragile and unstable conditions under which peace might—perhaps—exist. Installed in 1996 as a gift from the Italian government, the sculpture is the work of Arnaldo Pomodoro, a towering figure in postwar Italian art, who passed away in Milan on June 22, just one day before what would have been his ninety-ninth birthday.

Born in 1926 in the Romagna region and raised in the Adriatic town of Pesaro, Pomodoro did not initially pursue the path of the artist; trained as a surveyor and a technical draftsman, he arrived in Milan in the 1950s with a background in design and construction rather than fine arts. Yet the city’s vibrant artistic ferment, catalyzed by figures like Lucio Fontana and a constellation of avant-garde collectives, quickly absorbed him, and although he engaged deeply with experimental circles, Pomodoro always resisted the gravitational pull of formal movements, maintaining a fiercely individualistic approach to his work.

His relationship with the United States began in 1959, when he was invited to participate in New York from Italy, an exhibition mounted by the John Bolles Gallery in San Francisco, a seemingly modest opportunity that nonetheless inaugurated a decades-long transatlantic dialogue. Over the years, Pomodoro returned repeatedly to American institutions—teaching at the University of California, Berkeley, and at the California College of Arts in Oakland—while also exhibiting in major galleries and forging lasting connections with museums and curators. A turning point came in 1963, when one of his spheres was acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, signaling not only international recognition but also anchoring his presence within the evolving narrative of postwar art in the United States.

Photo © Terry W. Sanders

In 1995, Pomodoro founded the Arnaldo Pomodoro Foundation in Milan, an institution that today preserves more than two hundred of his works and stands as a monument to his long and restless exploration of sculptural form. Among the many public installations he created are the Grande Disco in Milan’s Piazza Meda, the Column that rises on the campus of Bocconi University, Novecento at the EUR Sports Palace in Rome, and the Sfera di San Leo in Milan’s Santa Giulia neighborhood—works that, in their monumental scale and meticulous construction, continue to engage in an ongoing dialogue with the architectural and historical contexts that surround them.

To encounter one of Pomodoro’s spheres today is to confront a shape that has, over time, become familiar—even iconic—yet whose internal tensions and structural fractures remain unsettling, unresolved. The seductive sheen of polished bronze, the immaculate curves and smooth planes, far from offering comfort, expose the fault lines that run through even the most seemingly ordered systems, reminding the viewer that all structures, whether mechanical, political, or metaphysical, are ultimately susceptible to rupture. “Public art is an act of responsibility,” Pomodoro once said. “Each sculpture is an open question we leave to the city, to the landscape, to history.”

Photo © Terry W. Sanders

Throughout his long career, accolades arrived steadily: the Henry Moore Grand Prize, Japan’s Praemium Imperiale, the Knight’s Cross of the Italian Republic, the Morandi Prize. But Pomodoro’s creative energies extended well beyond sculpture. He was also a scenographer, a designer, a curator, and a visual poet, leaving his mark on some of Europe’s most prestigious opera houses—including the Zurich Opera, Venice’s La Fenice, and Florence’s Maggio Musicale. In the 1980s, he designed sets and costumes for Rossini’s Semiramide and Gluck’s Alceste, and in 2004, he created the set design and monumental sculptural structures for a widely acclaimed production of Madama Butterfly at the Puccini Festival in Torre del Lago.

Yet no matter how far his artistic inquiries extended—into theater, architecture, or installation—it was always to sculpture, and in particular to sculpture situated in the open air, exposed to the light, weather, and rhythm of urban life, that he returned. For Pomodoro, art was not an object to be admired at a distance but a persistent, material question posed to time itself.