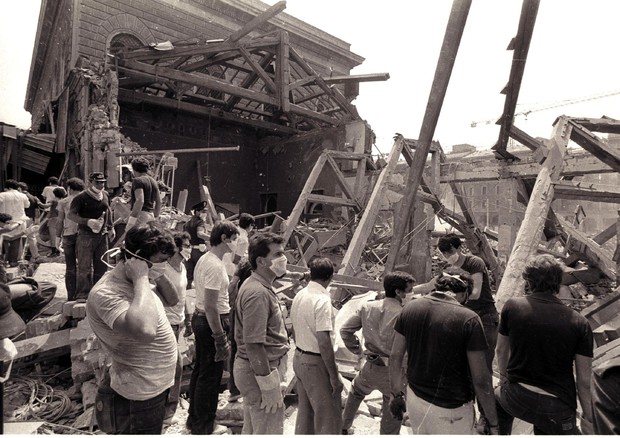

On Saturday August 2, 1980, a bomb exploded in the Bologna train station killing 85 people. After many years, four activists from Neofascist organizations were condemned as perpetrators. In 2020, another investigation concluded that the attack had been instigated by right-wing businessmen and politicians and by the Italian spymaster Federico Umberto D’Amato – all deceased. But why?

The United States knew its share of domestic terror attacks, like the bomb planted in Oklahoma City by Timothy McVeigh. But in Italy, the Bologna massacre was the tailspin of the so called “Lead Years”: in the 1970s terrorists from the right ripped public places with bombs; those from the left targeted politicians, journalists and judges. Many mysteries are still unsolved. This is a homage to the victims.

On Saturday, August 2, maybe Eckhart and Kai were sorry to leave. Two weeks in the warm sea; and the marvellous food and the ice creams. Kai was 8, Eckhardt was 14. Maybe their brother Hoger, who was 16, had been looking at girls in bikinis. Their father Horst Mader was a railway worker and had waited seventeen years for his first holiday with his wife, Margret.

On the morning of August 2nd, maybe Kai cried a little leaving their B&B on the Adriatic coast. We can only speculate on all these things.

On August 2, 1980, in Rome, I was getting ready to leave too.

A month away in a rented house meant moving home: clothes, house linen, kitchen stuff, seaside apparel. I was fifteen; my period had started that morning, and cramps were biting deep into my belly. My mother was banging things around and inviting me to “stop dawdling and help her”.

Here are the things we know for sure. On August 2nd, the Mader family was waiting for a train home.

When the bomb exploded, Horst was outside the waiting room. He turned to run back inside, but the room had collapsed on itself. His ears were ringing; the world was reduced to a fog of booming faraway sounds and swirling thick dust. He stumbled out looking for the other side of the building, near the spot where he had left Margret and his boys. He started digging with his bare hands.

He found Holger – maybe his arm first, or a foot with a shoe he could recognize. The boy had multiple fractures, but he was alive. Horst unearthed him.

Then he started digging again and he found Kai. The little boy was dead. Then he found Margret, who was dead too. He fainted when he found his second-born.

At ten twenty-five when the bomb went off, I was dragging myself downstairs to buy Ibuprofen from the corner pharmacy. I also forced myself to eat a piece of bread. Finally, I took a pill. In about half an hour, the pain started to fade.

There were many tourists at the station on that August day.

Catherine was 23 and travelling with her boyfriend John. They were English, recent graduates from university. Catherine had a blue rucksack; John’s was orange.

Iwao Sekiguchi was 20, a student from Tokyo on a grant. “I have decided to go to Venice. I will take the 11:11 train” he wrote in his diary. He bought some food for 5,000 lira. And he sat waiting for his train: “While I eat, I write.”

Every year, my father spent hours loading the old Fiat. He tried, then unloaded everything and tried again. I assisted him, longing for a future when I might toss a single bag in the boot of my car.

Mother would complain: “He spends the whole morning just arranging the luggage. I hate travelling in the heat.” Air-conditioning in Italian cars was still far away.

Lina, 53, was a housewife. Newspaper reports later said she loved to read, but she and her husband didn’t have much money. Her mother-in-law had won a small sum at the lottery and paid their holiday. They were supposed to leave on August 3rd. The hotel manager had called to say a room would be free a day earlier. Lina was identified by her brother-in-law.

That morning Father also picked up his mother, who was going to spend the month with us. Faith was the rock of Grandma Maria’s existence. When her son had come back from the war in 1945, he had openly declared his atheism and broke her heart. Grandma Maria went to church every day. She brought me to Mass on several Sunday mornings, until Father discouraged her.

When Father came back with Grandma, he looked grim. “Turn on the TV”, he said. “There was another bomb.”

“Where?”

“At the Bologna train station.”

Bologna, right in the middle of Italy. Coming from the South – Naples, Rome – you must pass through Bologna for Milan. And from Rome or Milan you must change in Bologna for the east coast – Ravenna, Pesaro, Ancona.

It was stifling in the car when we left. “At least when the Brigate Rosse attack, you know they know who they are after” Mother said. “But who wants to kill civilians at random?”

I didn’t know much about the Red Brigades, apart from them being communist terrorists. At school I’d heard the fascists were planting random bombs. Obscure magmatic forces moving in the belly of Italy.

Luca was at the railway station with his parents because, on Friday August 1st, they had been in a car accident on their way to the seaside. They were told on Saturday morning that the car would need extensive repairs. Luca’s parents decided to go on by train. They had to run to buy tickets in the crowded station. But they made it. Just in time to be there when the bomb went off. Luca was 6, Carlo was 32, Anna 28.

At the seaside house, Grandma Maria sat on a vinyl couch, pasty-faced. “I do not understand!” she burst out. Her mousy hair, up in its usual bun, straggled around her face. “If God is up there, how can he accept this?” She wrung her hands – the first crack I had ever seen in her. “But then, he must be there. He must! Because otherwise – everything is pointless – pointless.”