Born in 1964, Tony Gentile began this profession in Palermo, in 1989, the city in which he was born.

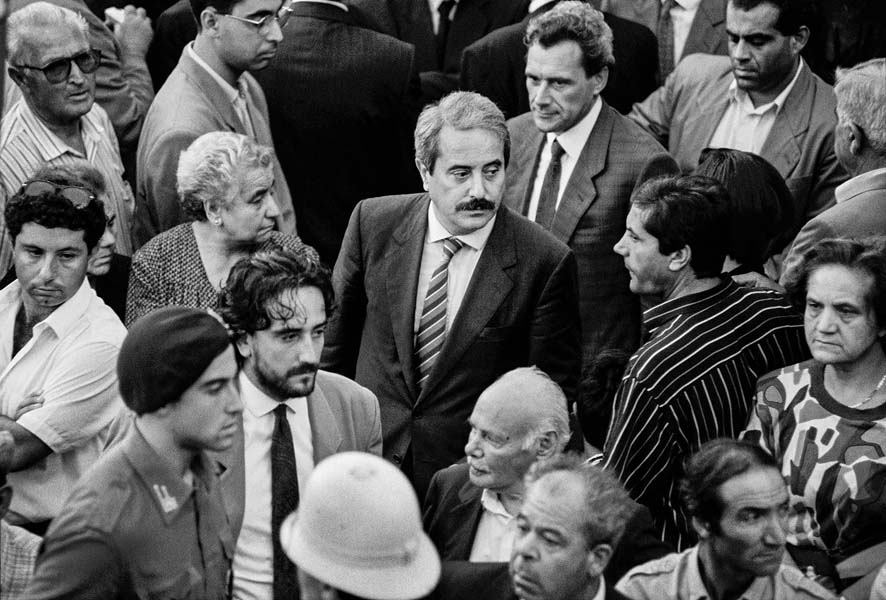

His name is known the world over amongst photographers, but for those of you who do not recognize it, there is no doubt that you’ve seen one of his pictures, some of which have, in fact, marked historical moments. Through his photographs, Tony has had the possibility to make an important journalistic imprint – in some cases, fundamental – to many world news stories. I interviewed him by telephone on the occasion of a court sentencing in Germany that in a way refers back to his most famous photograph: the one in black and white that immortalizes Falcone and Borsellino during a conference just before both were barbarously murdered. Falcone’s sister’s appeal against a pizzeria in Frankfurt, Germany, that had chosen the name of “Falcone e Borsellino” has just been dismissed. On the walls of the pizzeria, they hung Gentile’s famous photo of the two magistrates next to a picture of don Vito Corleone from the famous movie, “The Godfather”. A violation of the memory of the two Anti-Mafia magistrates that was denounced by judge Giovanni Falcone’s sister, Professor Maria Falcone. But let’s take one step at a time.

I’ve known Tony Gentile for some years. We met for the first time in Sicily, on the occasion of his exhibit. Over time, we continued our friendship always with mutual esteem, more or less at a distance and mostly by phone, even though we lived near each other. Our bond was the love that we share for the world of images. We know each other, along with our respective families. A life, that of Tony’s, spent in Photography and for Photography.

Tony, in the beginning you were collaborating in Sicily with a local daily newspaper, and at the same time with the photojournalism agency, Sintesi, in Rome. Thanks to Sintesi, you went on to publish your pictures in the most important Italian and foreign newspapers. Then came the turning point: in 1992, you became the correspondent from Sicily for the international press agency, Reuters, for which from 2003 to 2019 you worked as staff photographer based in Rome. What kind of observations did such an experience with international travel lead you to make regarding your work as a photographer?

“It’s not easy to talk about one’s actual work. I’ve had some luck in life, one of which is the opportunity to practice a profession which coincided perfectly with my great passion – photography. I then had the opportunity to work in an incredible city like Palermo, in which during the ‘90s, when I first started out, a terrible war was being fought between the Mafia and the government with bombings and high-profile arrests; a piece of our country’s history that unfolded right in front of those of us living in Palermo. I told that story as a very young photo reporter. Afterwards, I was given the opportunity to work for a really great international press agency, Reuters, thanks to which I reported on current events, customs, and sports that at times became part of our collective history. A lot of sacrifice, sweat and fatigue, that however bore good fruit, and always within the perspective of photojournalism that is meant to serve the reader more than the photographer. A photograph that is useful to others, to the people that observe and discover a fact, a story through the eyes of a journalist who was actually present and was an eyewitness; a photograph that has its foundation within the construction of memory.”

Your name has just returned in the news due to one of the many events that – at various times over the years – had to do with a particular photograph of yours, probably the most famous: the one that immortalizes the two magistrates Falcone and Borsellino together. An appeal by Judge Falcone’s sister has been resoundingly dismissed in Germany. What are your thoughts on the matter? You are also involved in this lawsuit with them, if I’m not mistaken. I believe that over the years there have been many lawsuits in which you’ve tried to defend your copyright on that photograph. It’s a picture that throughout the world is considered, both by photography and intellectual communities, as a symbol of the fight against the Mafia — but it was not considered as such by a German court.

“I would make a distinction between the two issues – the one concerning the use of my photograph, and the other concerning the feelings of family members. The second of these I personally consider to be of an unprecedented gravity. I believe that it is mortifying for the family members of Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino to imagine that their last name was used as the name of a pizza listed on a restaurant menu, and even more so, when the brand name is represented by an image that depicts gunshot holes. And to render things even more grievous, inside the pizzeria, the pictures of these two great martyrs are displayed alongside an image of an anti-hero, an imaginary one at that, which is the “godfather” played by Marlon Brando. Disgusting, to say the least. Regarding the improper and abusive use of my picture, I have never put up with it, and this has always caused me a lot of problems, but in this case my issue takes second place. The thing that outrages me the most is to think that a magistrate can speak of a colleague such as Falcone (he knows very well what happened to him) in such a manner – and here I quote ANSA (the leading wire service agency in Italy) directly: ‘the judge worked primarily in Italy, and in Germany is known only by a restricted circle of insiders, and not to the common people that go the pizzeria’. I feel shame for him.”

What is the most resounding action that you have pursued to protect your rights as a photographer on the copyrights of one of your pictures?

“I’ve had so many controversies — not all of them have gone to court – but this last one is the one that outrages me the most. And the politicians that use this photograph purely for propaganda purposes outrage me as well, and for this reason a few months ago I warned them against using the photo in question, but we all know that it’s a battle between David and Goliath, and David does not always win.”

What would you suggest to a young person who is interested in a career like yours? Is it worth it to practice such an abused profession?

“Instinctively, and knowing the facts as I do now, I would say ‘No’. But then I think back to the end of the ‘80s–more than 30 years ago– when I asked the same question of another photographer who was already practicing the profession that I aspired to, and he answered ‘No.’ I still decided to pursue it, and I dedicated a lot to this profession and in the end, I was successful. Everything that life has given me I was able to achieve through this work and thanks to photography. So if that young person is determined and is talented, he should give it a try, and so my answer is absolutely ‘Yes’. Because in the end it is a really beautiful profession, despite everything and everybody.”

Photography for you is…

“It would occur to me to answer that photography for me….has been. Today, I no longer do the work that I’ve done for 30 years and I don’t regret this. The world of photojournalism has changed a lot and perhaps is no longer for me. Photography, however, will never die, and especially it will never die inside of us. You can do it at any age, without time limits. As a great Maestro used to say, ‘photography is done with the eye, the brain and the heart, and these three elements never retire.’”

Two questions that I’ve been meaning to ask you for many years, yet I never have: the first one is, who do you consider to be your mentor?

“There is no one teacher that I could identify; there are so many photographers that, voluntarily or involuntarily, I took inspiration from. Amongst these, however, there are two that I can’t not mention: Letizia Battaglia and Franco Zecchin. I grew a lot from the human point of view, and then also from a photographic one, thanks to their photographs. They’re a couple of photographers that are different from each other, but that to my eyes as a high school student passionate about photography, appeared to be one single thing. They represented for me a continuous and strong source of stimulation towards the civic rise against the Mafia, and towards a profession that also carried within itself a sense of commitment to raising consciousness.”

The second question: which would be the one photograph of yours that – should you burn them all – would be the one you’d save?

“I’m firmly convinced that one of the fundamental values of photography is memory, and despite the fact that I have a very conflictual relationship with my photograph of Falcone and Borsellino, I feel that I would definitely save this one. It’s no longer a picture, but an icon, and this icon is a symbol of redemption for so many people, for the generations that lived those terrible moments, for those who were born afterwards, and I believe also for many of those that are still to be born. For this reason, I consider this photograph to be sacred, untouchable. The war against mob culture hasn’t been won yet, and until the end, I believe that this image represents a banner of hope, a small hope for change, and for this reason it should be protected, because it’s more useful to others than to me.”

What do you hope that people will remember about the professional Tony and the private Tony?

“I have no idea; I’ve never posed the question, and I hope not to for some time still.”

Your future projects?

“Lately, I’ve been dedicating myself to a photography that is slower and more reflexive with respect to the rapid one that I practiced for my work up until not too long ago. I hope to be able to produce an editorial project in 2021. Besides this, since I’ve always been passionate about moving images, I’m working on documentaries based on a few stories that are very close to my heart and that I hope one day will be able to be viewed by others.”

My best wishes go to Tony and to his future photographs; knowing him, I have no doubt that he will continue to touch both our imagination and feelings, just as he did with that symbolic photograph of Falcone and Borsellino that the entire world will continue to look at. An image born from the instinct and talent of a young provincial photo reporter who has come a long way, and whom we thank for always giving so much from the heart.

Here, the video about the book by Tony Gentile La Guerra (The War).

Tony Gentile – la guerra from Tony Gentile on Vimeo.

Translation by Emmelina De Feo