When I was a graduate student at Columbia University, dad bought you a ground floor apartment in the tenement walk-up on East 61 Street, where first you lived with Nonna for over thirty-five years and then on your own for another thirteen. Your emphysema no longer allowed you to walk up four flights of stairs, but before you could even move in, your condition worsened and you had to go into the Mary Manning Walsh nursing home on East 72nd Street. In the end, I moved into the apartment with my girlfriend, just down the street from your sister and brother and other members of the two-square-block diaspora of Northern Italians, where language and culture continued to resist the corrosive effects of a bustling metropolis.

***

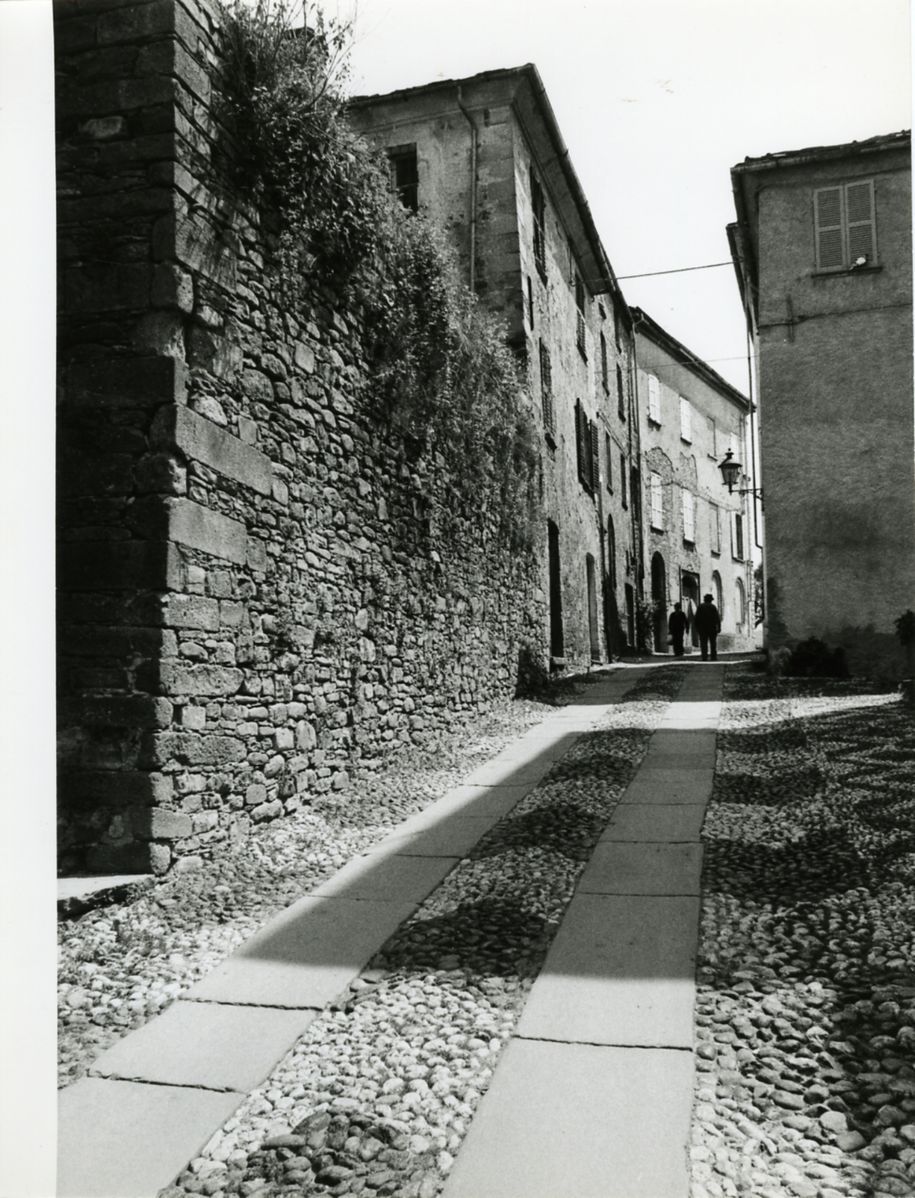

Four years later, I retraced your steps back to the Old World, going to live in the medieval hilltop town of Compiano in the Province of Parma, overlooking Isola di Compiano and Piano delle Moglie, the frazioni (hamlets) where you and Nonna were born. There were several similarities in our situations. Like you, I didn’t know the language (though, unlike you, I wanted and had to learn it if I was to survive). I also had a support group in my new country: the many relatives from both your and Nonna’s side in the two hamlets. And I, too, had no economic incentive for going to a new land. My dad would always tell us there was no reason for you to emigrate to America. In fact, your partner developed the itinerant haberdashery business into a stable enterprise that allowed him to build an elegant home in Bedonia and buy his son a Ferrari.

The Italian backdrop became fertile terrain for the images of you that would sprout forth, different scenes at different times spontaneously fading in and out in apparent discontinuity. A simple chair and table – a spartan set – with a taciturn figure slightly hunched forward, hands clasped together cradling a glass of table wine, the gallon jug of Gallo wine in the background, never too far out of reach. Every time you visited us during my high school days you would bring a full jug, which would inevitably be empty by the time you left several days later.

The image fades to darkness. Soon, however, the stage lights of my memory are lit, revealing another scene: a short, square-shaped old man walking along the sidewalk of a rustic New England town, a plastic sack in each hand. The suffused softness of the light indicates it is dawn, as does the fact that there is no one else on the street. There is a noticeable limp to your gait, and you continually pause after several steps, a respiratory ailment sapping all your wind. You could have asked for a ride, but you never wanted to disturb anyone, preferring to walk the mile-and-a-half to the train station weighted down and struggling to breathe.

How much we were alike, Nonno. I too have awoken at daybreak, enjoying the tranquillity as darkness fought its losing battle with light. I heard the door slowly open and your footsteps as you entered the room to leave me a five-dollar bill. I pretended to be asleep, waiting to hear the front door close before I went into the kitchen, knowing I would find the grapefruit you had placed in a bowl on the table for me, each wedge carefully cut round so that it could be easily removed. I never told you I loved you, Nonno, nor you me. But there was no need to. The hundreds of grapefruits you prepared for me expressed that feeling better than words could.

Fast-forward one hour. As I drive into town, I spy you on the sidewalk, having covered only three-fourths of the distance to the station. Part of me is angry at your stubborn pride, but another part is moved by the poignancy of the moment. I understand you, Nonno, and that’s why I don’t stop to pick you up. I know you would want it that way.

***

Like many second-generation Americans, I had an ambivalent relationship with my ethnicity, especially after my family moved to Waspish New Canaan, Connecticut, in my first year in Junior High School. I didn’t go out of my way to advertise the fact that my grandparents and father had emigrated from the Old Country. At that time, polenta had not yet become trendy, not to speak of Tiramisù. I tended to keep under wraps any of the trappings of my Italian heritage, fighting against all its manifestations: accordion lessons starting at age six, when my father brought back from Italy a Stradella accordion that was almost as big as I was, or the discomfort at being fed cotechino, polenta and pasta e fasul (though I didn’t mind the times I was given a glass of 7-Up with a bit of red wine mixed in).

There were moments, however, when ethnic pride would break out despite myself, as happened to the immigrant in the 1974 movie, Pane e Cioccolata (played by Nino Manfredi) who burst into euphoria when the Italian National Team scored against Germany in the World Cup, giving l’ombrello gesture (the crooked arm, f_ _ k off gesture, the so-called Italian Salute) to the patrons in the Swiss pub he was watching the game in. I would usually invoke Italian sports stars, that none of my friends had ever heard of, of course: the great alpine skier Gustavo Thoeni, the Olympic bobsled champion Eugenio Monti, or the 1970 Italian national soccer team, World Cup runners-up to Brazil.

But more often than not I would feel embarrassment, for example, when my friends came around and I would shuttle them past you expeditiously, keeping the interaction time brief to avoid you having to utter anything in your primitive English, or the time a neighbor complained because she had seen you peeing against the tall oak tree on the front lawn in broad daylight. Though I had already started to grow out of this cultural denial phase before I moved to Italy, I didn’t get a true perspective and appreciation of my family roots until I came here to live in my late twenties.

The interesting thing about perspective is that we usually have to step back in space or time to have it. The feelings that accompany my recollections of you now are different than those I felt in my early youth, and it could be no other way. I am able now to understand the nuances of our relationship and go beneath the surface, to understand that embarrassment or frustration wasn’t really that at all, merely the outward sign of more complex emotions.

***

After all these years, I wonder what it would have been like to speak to you in Italian. I didn’t know the language growing up, though somehow we managed to communicate. I would speak to you in English and you to me in Italian, most of which I managed to decipher. But I don’t remember feeling any awkwardness because of the difficulty in verbal communication.

Years after you had died, I came across an old, curled black-and-white photo of you and me sitting under the off-ramp of the Queensboro Bridge, on 61st Street, between First and Second Avenues. We were sitting on a low cement wall in front of a large chain-link cage that served as a recycling center. You had placed a section of newspaper under me to make it more comfortable and were sitting in your typically rigid, upright pose, without a hint of a smile. Though it was the middle of summer, you had your white short-sleeve shirt buttoned all the way to the top. I was slightly hunched over, hands on knees, my contentment with being there evident even through the slightly bored expression on my face, the default look of pre-adolescence.

As I continue to examine the photo, I smile to myself. There is a gap between us on the wall, symbolic of a cultural and generational divide that existed at that time. The physical distance was bridged that day by your hand reaching across to firmly grip my knee, your way of showing stoic affection. The cultural gap would be bridged years later when I became immersed in your world, its language and culture, which you had brought with you to America and passed on to me, but that I could only willingly accept by discovering it first-hand on my own terms.