From the highest terrace of the Statue of Liberty pedestal I look out at the sea in front of New York. I think of the ships full of immigrants that passed by a century ago, a few hundred meters from where I stand now. Visualizing them is easy. I have seen them in a thousand vintage images.

Men, women and children lean out on the balustrades of the boat on which they have just crossed the ocean to look at New York and greet the Mighty Woman. I feel the anxiety they must have harbored in their hearts, but I also feel the joy and anticipation of what their American future would have in store for them.

I am an immigrant too, there’s no point denying it. A “luxury emigrant”, possibly, as an Italian acquaintance once labeled me on Facebook a couple of years back. I came to the US by choice more than necessity. And I certainly cannot say that I settled for a humble job. Yet I share a lot with those immigrants from 100 years ago. Leaving one’s country to move into a new one indefinitely is an important step, laden with defining moments that represent milestones in a person’s life.

I remember when the plane carrying me and my family took off from Fiumicino on a day in October 2011. We were tired. We had risen very early. The first light of dawn allowed me to see the airport as it drifted away from the window. I wouldn’t speak of sadness, but I was aware that an ancient bond was being severed at that precise moment.

I remember what had happened a month earlier. The defining moment when I learned that I would move to America with the family. For an instant, emotions had overwhelmed me. Emotions that surely must have resembled those of the expatriates who sailed by, be they Italian or not.

Cary, my American visa attorney, had assisted me in that operation. As the inventor of a fairly well-known software component, I was eligible to apply for a work visa reserved for experts in their respective fields . In the summer of 2011, my company applied for a visa at USCIS, the US Department of Citizenship and Immigration Services .

Cary had given me a link to the USCIS website and explained to me that I could check if my application had been accepted there. Checking the site directly was faster than any other official notification we might receive.

I took the habit of checking that page at least once a day, maybe twice. At some point, I became casual about it. Checking without really thinking. I think that, for some weird subconscious reason, I expected the page to say ‘ in progress‘ forever.

On a warm Roman day in September, the page appeared different. Greener. I paused for a few seconds. My application had been accepted. I remained calm, yet something had touched me inside. I shouted to my wife to come over. Tatiana did not immediately understand why my eyes were teary. I broke the news to her.

All of a sudden what had just happened was very clear. I had told America: “I am cool. I will start a successful company in the US. Let me come there.” And America had replied: “OK, Luca, I believe you. Come here. Show me what you can do”. It was enough to make a grown man cry.

The day before

What a pain in the neck when they move meetings on you on short notice. I had arrived in New York the day before to be on time for a meeting in the morning, but I would not swing into action until 4 pm.

The previous evening

“I don’t think so, sir” – the reception clerk tells me – “Without a reservation everything will probably be fully booked. Try going early in the morning. Take subway line 4 or 5 from here to Bowling Green. Maybe you can buy a ticket there. Be advised that it’s going to rain tomorrow.”

The morning

I take a picture of the ticket with ‘her’ far in the background. The boat is half empty. Despite the bad weather, tourists go up to the boat’s outdoor level and take pictures of the Statue of Liberty as she slowly approaches.

There is euphoria in the air. The icon of New York, or I should say, the icon of America, has an ancient and undeniable appeal on everyone. One cannot watch a lifetime of American movies and not fall prey to excitement as she closes in from the sea in all her majesty.

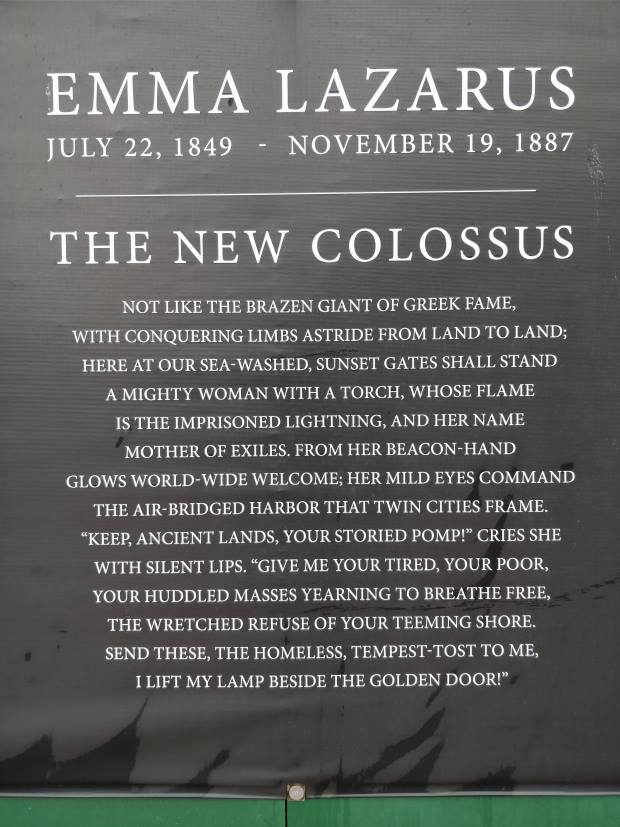

The boat moors at a marina behind the statue. Almost everyone disembarks and heads towards the entrance to the pedestal. I linger behind at the construction area of the future Statue of Liberty museum. The enclosures to the working area offer me the verses of the famous sonnet that Emma Lazarus wrote in 1883, specifically to raise money for the project.

The New Colossus of Rhodes

It has nothing to do with the imperious giant of the port of Rhodes.

Coming from the sea, crossing the gates of the sunset, a woman will rise majestically. Her flame is the subjugated lightning. Her name is Mother of the Exiles.

The light in her hand radiates welcome to the world and her gentle eyes dominate the sea between Manhattan and Brooklyn.“Keep for yourselves, ancient lands, your renowned grandeur,” she cries without moving her lips.

“Give to me the tired and poor crowds who long to breathe free.

Those I want, the losers who are on your shores, the homeless tossed about by the storms.

For them I raise my torch and light up the golden door. “

(rendering in English of the Italian translation by Luca Passani)

Wow!

What a difference between that booming America and the America of today, headed by a president who does not want immigrants from “shithole countries”.

I enter the pedestal, where the museum of the Statue of Liberty is still housed, but my mind is stuck on the same thought. Why do people emigrate? What has changed between then and today? Can we make a parallel between the situation in Italy today and the American one 100 years ago? Rejecting and sending illegal immigrants back is the right of every country. How can we handle the phenomenon of illegal immigration ethically?

Those are tough questions, each of which leads to even tougher questions on the purpose of states and their governments, on human condition, on the differences between the immigrants of those times and the ones of today, on how the concept of work will change in the years to come as artificial intelligence and robots beat humans even at intellectual work.

A museum employee ‘slides’ in front of me. Her job is to clean the brass bar that keeps visitors away from exhibition items.

I wonder what the lady thinks of her job. Were she Italian, she would almost certainly be complaining that her job sucks every single day. After six years in the US, I would not be surprised if the lady considered her job in the Statue Museum prestigious and felt totally satisfied with her role (possibly with a little help from the health insurance provided to all federal employees).

After all this is the beauty of America: they teach everyone to go look for their own happiness from childhood, and not to harbor resentment when you suspect that others may be happier than you.

Is this the secret ingredient that makes the US such a strong nation?

I start climbing the 190 steps that take me to the terrace at the base of the pedestal. I go out to meet the open and windy air. I also yearn to breathe free after that climb.

From the terrace I see Ellis Island and, behind it, Wall Street. I find myself alone with the realization of being an immigrant myself in America. I think back to the day I moved to the US with my family and the period that preceded that moment.

I descend and exit the building. It starts to rain again. I run towards the arbor that shelters tourists waiting to board the boat for Ellis Island from the bad weather. Two American girls mock the typical New York accent with which one of the employees shouts “New York” .

By now, time is running out. I have to go back to the hotel and get ready for my afternoon meeting. I just don’t have time to see the museum. Screw it. Next boat is in 20 minutes. I decide to go in anyway.

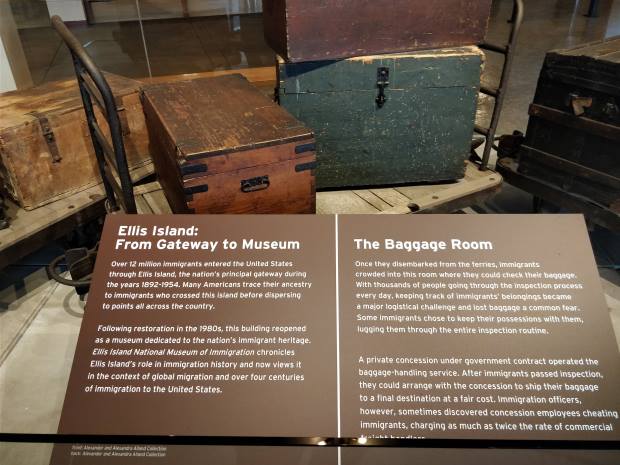

School children and other visitors huddle at the entrance to the Ellis Island museum.

The museum is huge and fascinating.

I step inside a few random rooms. The baggage area. Daguerreotypes of immigrants in different moments. A statue illustrating a medical examination. Computers on which everyone can find the names of their more or less distant relatives who entered the country.

I am in the rooms that illustrate the process of naturalization. I watch the video of new naturalized citizens taking the oath and I seriously run the risk of being overcome with emotions again.

That’s enough. Catching glimpses of some random images makes no sense. And also too many emotions in one morning for me.

I want to come back here and visit this museum properly. And above all, I want to come back with my family. If we will be Americans one day, it will be because we have come here to ask ourselves questions and look for the answers.

PS: For an exceptional rendition in Italian of the sonnet by Emma Lazarus I invite everyone to read the translated sonnet by Joseph Tusiani .

PPS: I would like to thank Joe Ganci and Jessica Pineda for reviewing this article and providing feedback and corrections. Thank you, guys.