Clark Olofsson, who has died at 78 after a long illness, was never simply a bank robber, a repeat escapee, or just another name in the criminal archives of 1970s Scandinavia. He was, unwittingly, the face of a psychological paradox that would fascinate psychiatrists, criminologists, journalists, and novelists for decades. With him—and with a tense standoff in a Stockholm bank vault—an expression entered the global lexicon: Stockholm Syndrome.

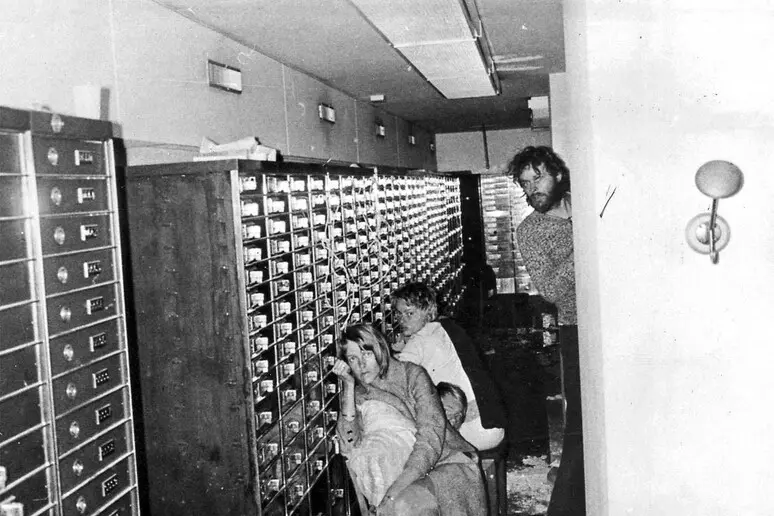

It all began on what seemed like an ordinary summer morning: August 23, 1973. Jan-Erik Olsson, armed with a submachine gun, stormed into a bank in downtown Stockholm and took four hostages—three women and one man. In a move that confounded logic, he demanded that Swedish authorities bring in a fellow inmate he had once shared a cell with: Clark Olofsson, who was then serving time for robbery.

In an attempt to prevent bloodshed, the authorities agreed. Olofsson entered the bank not as a negotiator or mediator, but as an accomplice. And yet, over the course of the six-day standoff, the expected dynamic of victims and aggressors began to dissolve into something more complex.

Kristin Enmark, 23, one of the hostages, spoke repeatedly on the phone with Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme. Calm and composed, she never pleaded for rescue. Instead, she asked to leave the bank alongside her captors. “I completely trust Clark and the other man,” she said. “They haven’t harmed us. On the contrary, they’ve been very kind. We tell stories. We play checkers. It’s absurd, but we feel safer here than outside.”

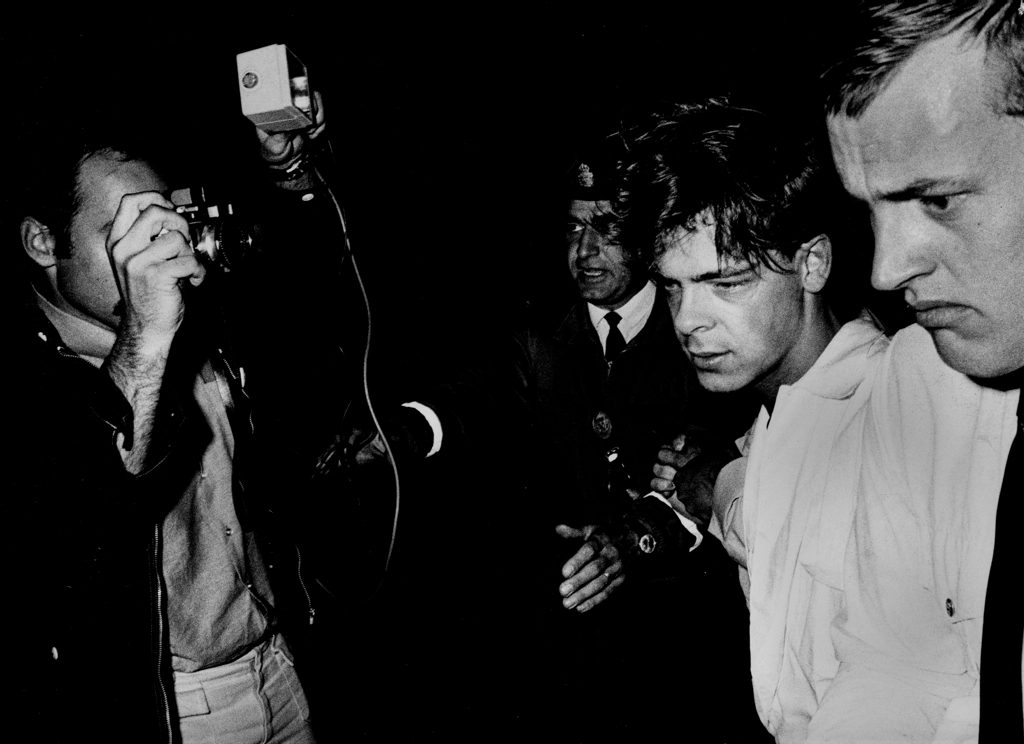

Her words stunned the country—and the world. The siege ended with a burst of tear gas dropped from the roof. The assailants were arrested. The hostages were unharmed. But what lingered was something harder to explain: how could a young woman—free to speak, intelligent, uncoerced—defend the men who had deprived her of her freedom?

Out of that dissonance, a psychological theory was born. Psychiatrist and criminologist Nils Bejerot coined the term “Stockholm Syndrome” to describe the emotional bonds that hostages can develop toward their captors under extreme stress—a subconscious survival strategy that sometimes leads them to identify with or even defend their aggressors.

With his long hair, beard, and piercing gaze, Olofsson became the ideal symbol of that ambiguity. He wasn’t a sadist. He could speak, persuade, charm. “I promised Kristin nothing would happen to her,” he later said. “And I kept that promise.”

Olofsson’s life after the bank siege followed a predictable script: more crimes, more arrests, more escapes. Between Sweden, Belgium and Germany, he spent more time in prison than out. His final release came in 2018, after serving time for drug trafficking. Yet the myth of Clark remained. In 2022, Netflix dramatized his life in the series Clark, starring Bill Skarsgård—a darkly comic tribute to a man who never apologized, but never stopped fascinating.

Still, the story that made him infamous remains wrapped in uncertainty. What exactly is Stockholm Syndrome? A medical condition? A survival reflex? Or just a label used when reality refuses to follow a script?

In 2021, Kristin Enmark rejected the concept entirely during a BBC podcast. “It’s just a way of blaming the victim,” she said. “I did what I had to do to survive.”