A historic election is about to change the face of Mexico’s judicial system, but not without raising serious concerns. On Sunday, for the first time in the country’s history, nearly 8,000 candidates will compete for the popular vote to replace all federal and state judges. This radical shift, driven by former president Andrés Manuel López Obrador, has sparked intense debate over the risk that such a reform could undermine the independence of the judiciary and open the door to interference from organized crime.

Throughout his presidency, López Obrador frequently criticized the judiciary, arguing that judges had excessive salaries and were influenced by external interests.

In February 2024, at the end of his term as president, he introduced a package of 18 constitutional amendments, including the proposal to elect judges by popular vote instead of appointment-based selection. The ruling MORENA party (Movimiento Regeneración Nacional), led by López Obrador and later, current president Claudia Sheinbaum, supported the reform, claiming it would eliminate corruption and make the judiciary more accountable to the people. However, critics argue that it threatens judicial independence and could politicize the courts.

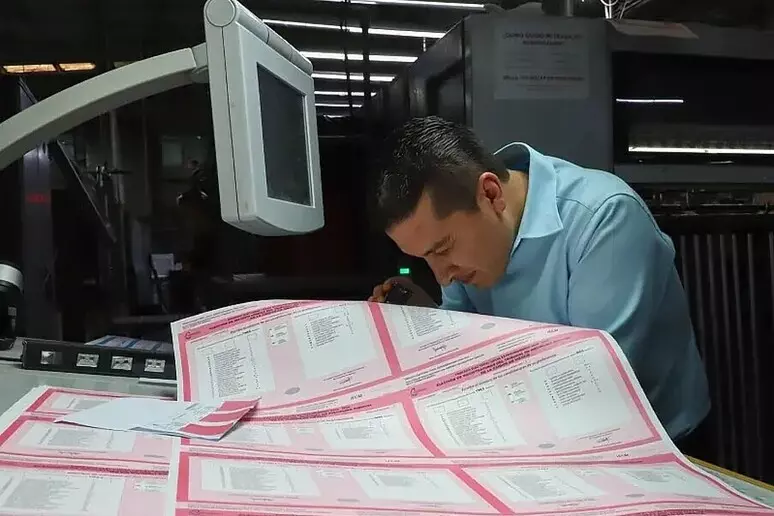

The electoral mechanism will resemble a regular public vote, but with some complications: for instance, 64 candidates are running for just 9 seats on the Supreme Court, and voters will have to make their choices with limited information, since the candidates are not featured on TV and rarely give interviews. The Electoral Commission has published their résumés online, leaving citizens to research on their own. This has raised doubts about voters’ ability to make an informed decision.

Even more alarming are reports that numerous candidates may have ties to the criminal underworld. Dozens of individuals are suspected of having connections to drug cartels; in some cases, judicial hopefuls are even former inmates with drug trafficking convictions. The vetting process has proven ineffective, marred by irregularities such as extremely short interviews or none at all.

Despite sharp criticism, some legal scholars defend the reform, emphasizing that judicial institutions must remain independent from politics to ensure fairness and justice. One Supreme Court judge, however, described the election as a “historic mistake” that will weaken the system and compromise its autonomy.

Monica Castillejos-Aragon, a former advisor to the Mexican Supreme Court and now a professor of comparative law at UC Berkeley in California, explained that the reform represents a return to the days of authoritarian regimes–though in more sophisticated forms. According to her, the ruling MORENA party is effectively executing a full-scale power grab, following models of authoritarianism seen in other countries, such as Hungary.

Since this is a constitutional change, it will be very difficult to reverse, and Mexico will have to deal with its consequences for many years to come.