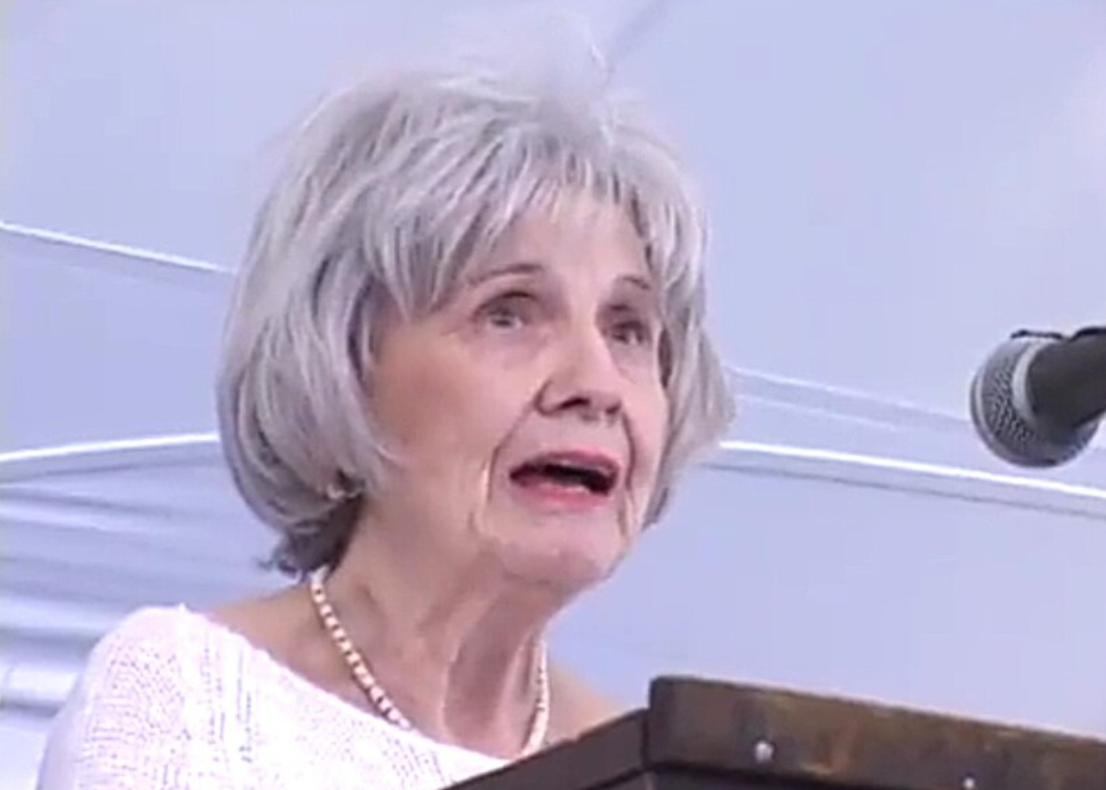

Recent reports have surfaced involving the late Canadian Nobel laureate Alice Munro, where her daughter, Andrea Robin Skinner, has made allegations of sexual abuse against her stepfather, Gerald Fremlin, who was Munro’s second husband.

Skinner, her two older sisters, and her stepbrother have been living with dark secrets for more than fifty years. Fremlin sexually assaulted Skinner in 1976, and Skinner told her mother in 1992, after which Munro remained married to Fremlin until his death in 2013.

Skinner claims that the abuse began when she was nine years old and continued for several years. In a poignant essay, Skinner details her experiences and expresses the profound hurt and betrayal she felt, particularly in response to her mother’s reaction upon learning of the abuse.

Munro, who passed away in May at the age of 92, is said to have remained with Fremlin despite being informed of the allegations.

This has sparked a complex conversation within the literary community and among Munro’s readership about her legacy, and exposed the abyss that often exists between publicly expounded beliefs and private actions that contradict them. In one of her most notable works, “Lives of Girls and Women,” Munro delves into the coming-of-age of a young girl and the challenges she faces.

The more brutal questions that surface are: was Munro a hypocrite? Were her feminist ideas merely literary posture?

Munro’s fiction often revolves around the cause of female rights and independence. Focusing on the lives of common people, her novels and short stories are women-centric, detailing their life conditions under unfair social conventions, and especially on familial dynamics.

The revelations have prompted a re-examination of Munro’s life and work, underscoring the often painful and complicated realities that can exist behind public personas.

In 2005, Skinner could no longer ignore the trauma and went public, reporting the past abuse to police, using Fremlin’s own letters threatening to commit suicide as evidence. As a result, Fremlin pleaded guilty on arraignment without trial to “indecently assaulting” Skinner. Fremlin, then 80, was sentenced to two years of probation, Skinner wrote.

In the past, Skinner had told her stepbrother Andrew about the assault soon after it happened, after having visited her mother and her new husband in Clinton, Ontario, during summer vacation. She told him that Fremlin had climbed into her bed and touched her and himself while she pretended to sleep. At other times, he had made inappropriate comments to her, talked to her about his and her mother’s sexual activities, and asked her about her own.

Unsure of what to make of it, and perhaps seeking reassurance, Andrea tried “to make a joke of it.”

“He didn’t laugh,” she wrote. “He said I should tell his mother right away. I did, and she told my father [with whom she was living], who decided to say nothing to my mother.” A conspiracy of silence continued after the revelations, but her older sister Sheila Munro was sent along with Skinner to make sure she wasn’t left alone with Fremlin.

“I don’t remember the exact conversation, but my father told me that Andrea had been molested, or something to that effect,” Sheila said. “There wasn’t a lot of detail about what happened to her.”

The abuse continued on subsequent visits, but Skinner thought she was handling it well. As it turned out, the lifelong consequences of migraine headaches and other physical symptoms persisted through the years.

“When I tried to tell her how her husband’s abuse had hurt me, she was incredulous,” Skinner wrote of her mother. “‘But you were such a happy child,’ she said.”

Munro was devastated, but according to Skinner, more focused on her own pain than her daughter’s. “She reacted exactly as I had feared she would, as if she had learned of an infidelity,” Skinner wrote.

In a stunning incongruity with the beliefs that Munro expresses in her fiction, “She said that she had been ‘told too late,’” adding that, “She loved [Fremlin] too much, and that our misogynistic culture was to blame if I expected her to deny her own needs, sacrifice for her children, and make up for the failings of men. She was adamant that whatever had happened was between me and my stepfather. It had nothing to do with her.”