A few days ago, on April 18, Columbia University President Minouche Shafik called on and authorized the NYPD to “begin clearing the encampment from the South Lawn of Morningside campus” that was set up to protest the war in Gaza and call for the university’s divestment from companies profiting off of “Israeli apartheid, genocide and occupation in Palestine”, an academic boycott of Israeli institutions via the cancelation of the Tel Aviv global center and dual degree program.

In response, the NYPD employed its Strategic Response Group to arrest over 100 protestors, the most since the 1968 Columbia University protests, as well as several legal observers that were there to document the police’s actions. In his comments about the removal of protesters, NYPD Police Chief of Patrol John Chell punctiliously clarified that it was Shafik, and not the NYPD, who had identified the demonstration as a “clear and present danger” and therefore initiated police intervention on the campus. He further commented in what reads as an implicit rebuke to the President, “To put this in perspective, the students that were arrested were peaceful, offered no resistance whatsoever, and were saying what they wanted to say in a peaceful manner”.

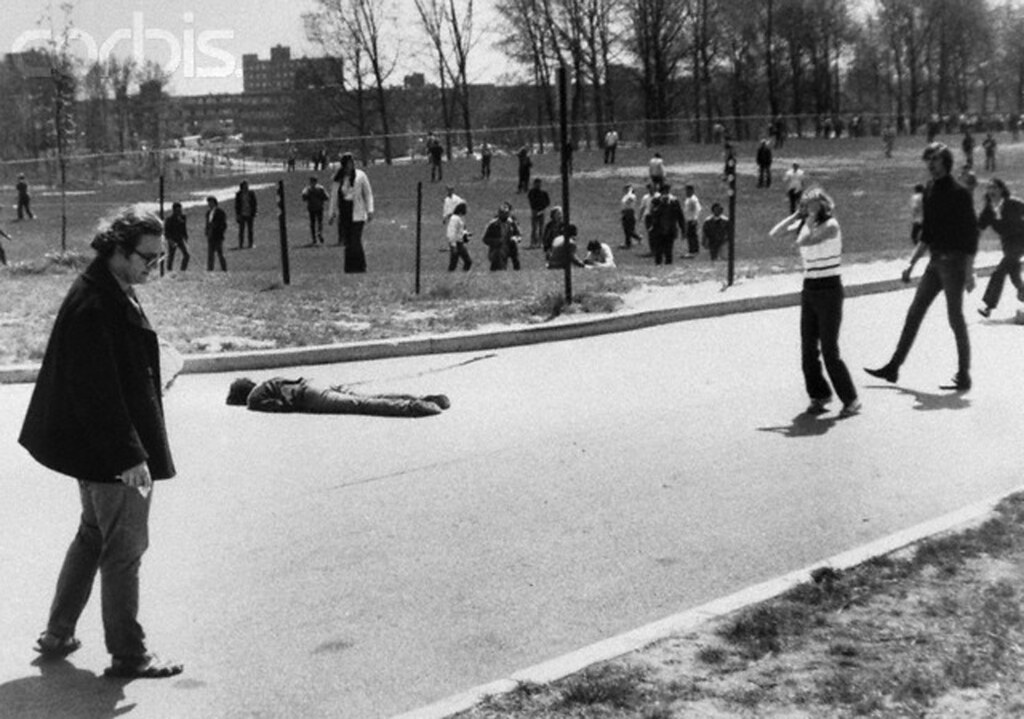

For history buffs or those old enough to have lived through them, today’s protests bear an undeniable similarity to the anti-Vietnam war student movement of the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. Shafik’s request for police intervention on campus is disturbingly reminiscent of the more violent clashes that occurred in the 1960’s and raises the specter of the Kent State tragedy, when a similar intervention led to the tragic wounding of seven and the killing of four students.

Student protests have been a powerful force for political change throughout history, often reflecting broader societal tensions and serving as a catalyst for public discourse. At times, they have led to policies that changed history. The student protests against the Vietnam War in the 1960s were a manifestation of deeper and more bitter divisions in our society, correlations of the civil rights and women’s liberation movements. Today the anti-Israel protests whose steady expansion threatens to turn into a movement, are an expression of the widening gap between liberal and conservative forces in American society. Between the liberal embrace of diversity and call for justice for the world’s minorities, and the conservative fear of losing power and privilege.

Despite superficial differences of geographical locations and the key players involved, the underlying values remain the same: students demand an end to war, a call for peace, and justice for the underdog.

In the 1960s, students were galvanized by the impact of the deadly but “undeclared” war and the compulsory draft that threatened their futures and their lives, and a growing skepticism of government authority– especially in light of revelations about the misleading information provided by the Johnson and Nixon administrations. The small antiwar movement grew into an unstoppable force, pressuring American leaders to reconsider its commitment. Peace movement leaders opposed the war on moral and economic grounds. The North Vietnamese, they argued, were fighting a patriotic war to rid themselves of foreign aggressors.

Similarly, the anti-Israel protests in 2024 have been driven by concerns over the conflict in Gaza and the role of Western governments in supporting Israel, whose policies have been castigated by the global community, including the International Court of Justice and the United Nations. In January 2024 the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ordered Israel to take action to prevent acts of genocide as it wages war against Hamas militants in the Gaza Strip, when the death toll of Palestinians was already nearing the 30,000 mark, hospitals were being bombed on the pretext that they were harboring Hamas terrorists, refugees had been squeezed into a tiny sliver of land that cannot support them, and humanitarian aid was being prevented from reaching the sick and dying.

Save the Children offers this terrifying image: “Those who have survived the bombardment so far face the imminent risk of starvation and disease. Our teams are telling us of maggots being picked from wounds, and children undergoing amputations without anesthetic. Children are enduring and witnessing horrors, while the world looks on. The level of human suffering is intolerable.”

Students at Columbia University have called for divestment from companies profiting from the war and occupation in Palestine, echoing the anti-apartheid divestment campaigns of the past. Both movements, one against the war in Vietnam and the other against Hamas in Gaza, have utilized campus spaces as platforms for expression, with protests, sit-ins, and educational events designed to raise awareness and pressure institutions to change their policies. These protests have led to a Congressional hearing that resulted in the resignation of numerous presidents from Ivy League institutions.

The use of media has also been a common thread, with the Vietnam War being one of the first televised conflicts, bringing the horrors of war into living rooms across America. This exposure played a significant role in turning public opinion against the war. In 2024, social media and live broadcasts have similarly amplified student voices and the realities of the conflict, creating a global audience and a network of solidarity.

The daily images emerging from Gaza that show the total destruction wreaked by relentless IDF strikes; the images of dead innocent civilians, most of them women and children; the reckless actions of Benjamin Netanyahu who persists in defying any urging by President Biden for him to curb the violent and never-ending reprisals for Hamas’ October 7 murder of 1,200 Israelis and the capture of 200 hostages, have opened the world’s eyes to an intransigence that hints at bigger underlying agendas such as that of intentionally wiping out the population, or that of attaining regional domination in the Middle East through the steady expansion of the war.

Student protests have always been part of the generational divide, although today there is ample evidence that contrary to the past when young people were more predictably liberal, there is a strong contingent that adheres to the far right, especially among white supremacists.

Despite the challenges they bring, student protests have historically led to meaningful discussions and, in some cases, policy changes. They reflect the passion and commitment of young people to shaping a more just and equitable world. The similarities between the student protests of the 1960s and those of 2024 demonstrate the enduring nature of student activism and its potential to influence the course of history.

Eventually, the protests that started with students in the mid-1960’s spread to government officials, labor unions, church groups and middle-class families, as it climaxed in 1968. It was thanks to these anti-war activities, particularly large-scale resistance to military conscription, that the war came to an end with the withdrawal of U.S. forces and the suspension of the draft by January 1973.

The anti-Israel movement today is at a tipping point, and it may very well gather momentum, as the anti-Vietnam war movement did, and turn into a force to curb Netanyahu’s irrational expansion of the violence in Gaza. Student protest movements are the engine that change society, and the current one is building steam.