Paul VI established the “World Day of Peace”, and celebrated its first edition on January 1, 1968, amid the Vietnamese conflict. It worked, you might say: on the 30 h , the Vietnamese unleashed the Tet Offensive prompting Johnson to suspend the bombing and announce two months later that he would not run for reelection. On May 13, peace negotiations began in Paris, as did the withdrawal of U.S. contingents. 55 years later, Francis dedicates today’s day to “Artificial Intelligence and Peace,” almost as if the content of the term “peace” had changed.

AI, like any technological device, is today an eminent fruit of human creativity. Technology makes us human in the sense that it comes from our genius and restores us to our freedom and thus, dignity. The pope, always very concrete, invites us to reflect on AI because it too can be used for or against humans. This ambivalence, which challenges freedom and conscience, also inevitably touches the question of peace, because everything is connected as reiterated in Laudato si’. In this time of an exploding World War III in pieces, the pope calls for seizing the opportunities of AI and avoiding its risks.

If peace is to be understood in such a broad sense, how does the church then manage to match the vastness of the challenges? At Yalta, Stalin ironized about the pope’s divisions – they say. Outside that crudeness of political assessment, the disproportion between the Holy See’s universal mission and available means remains. Might this not lead to the view that Vatican diplomacy is unrealistic?

The Holy See has no interests of its own to defend and therefore is credible as an agent of mediation and intermediation. Its work, at once diplomatic and prophetic, can help create a “middle ground” where conditions can be set for encounter and not for confrontation. I use the language and metaphors created by Tolkien, the author quoted by the Pope on Christmas night: in The Lord of the Rings, Captain Aragorn and little Frodo undertake to bring peace to a world at. war. The former does so diplomatically and with the usual tools: the sword, alliances. The second aims at true “disarmament,” destroying the ring of power. The two paths walk together. but without the meek folly of the second, the first would have no hope of success. Plainly speaking: the Pope is not a political leader, but a universal pastor of the Church and calls for spiritual conversion, of hearts, through forgiveness and mercy. Without it, one can at best achieve a transition from one armistice to another armistice, not peace.

Which explains why Francis and the church are so strongly opposed to all war, to the point of being perceived as “equidistant,” in an apparent contradiction to the principle of “just” war. Very bitter to note this, but throughout human history, so many oppressions and injustices have been removed only through violence and war!

Certainly, there have been wars that have produced moments of peace, but always partially. The pope, returning from Malta in 2022, explained that man tends to use patterns of war instead of patterns of peace. One such scheme is based on defeating the enemy, but it is deceptive, not decisive. Victory against Nazi-fascism did not lead to peace but to the transition from a “hot” war to a cold war, with attached continuing crises (including nuclear). Victories do not eradicate the root of conflict; on the contrary, they are often prodromes for reorganization leading to the next conflict. Instead, there are other examples to follow: Mandela and Tutu worked on peacemaking already during apartheid and imprisonment. In those very years, they sowed the deep roots of forgiveness and mercy. Dostoevsky, beloved by the Pope, reminds us that the struggle between good and evil has the human heart as its battlefield. That is the field on which to act.

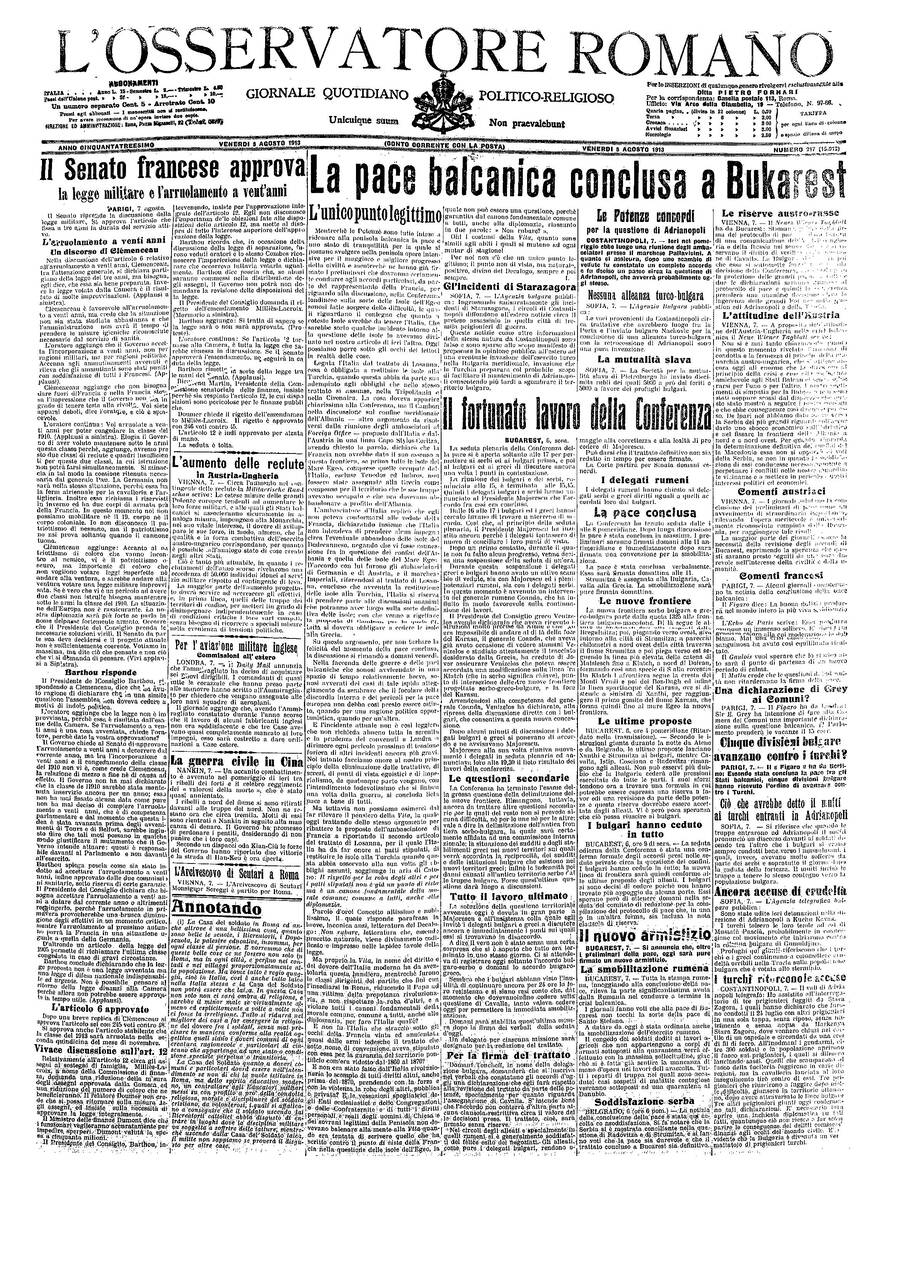

What contribution can newspapers, such as L’Osservatore Romano and La Voce, make towards peace? The sowers of hatred, nationalism, supremacism, find in social media endless space from which to fire on the ambulance of good information, more thoughtful and meditated. What should be done to bring people back to read newspapers and better reflect, for example, on peace and war?

We need to reflect on the content and language of communication appropriate to the time of obsolescence of newspapers. As for content, the words of the Pope at his Christmas homily – “… to say ‘no’ to war one must say ‘no’ to weapons…. People … ignore how much public money goes to armaments. … Let it be talked about, let it be written about, so that the interests and gains that pull the strings of wars are known” – are addressed to us communicators: wars are rooted in interests and ideologies far removed from the needs of peoples. The Pope calls on information workers not to serve those interests, but rather to unveil them, to talk about them. As for style, I can say that L’Osservatore Romano has been trying for years to talk less and listen more, giving voice to those who do not have it: the poor (in the monthly “L’Osservatore di strada”), and the young (in the column “Cantiere giovani”), in stories that come from war-torn territories (with interviews and correspondence). It can be said, without irony, that we try to avoid the risk of “pontificating” by listening. This is the first step for peace. After all, the Church is from the outset a widespread and capillary network, and this allows for a narrative that, in theory, no other newspaper can afford.