In the midst of the Civil War, on May 14, 1864, in the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, George Richardson posted a two-hundred-dollar reward in the Daily Dispatch for the return of his runaway slave, Henry.

On the same day, Italian padrone, Pasquale Falvella posted a reward in the New York Herald for the return of Antonio Pricolo, an eleven-year-old Italian harpist who was missing. But the boy wasn’t lost; he and six other Italian youths had escaped from Falvella, who was a brutal taskmaster. Remarkably, Antonio managed to evade his captor for over a year. Determined to find the boy, Falvella published additional rewards for his capture, raising the bounty each time. Whether he remained free or was eventually recaptured, Antonio’s fate is unknown. However, his story is not unique.

In the decade following the end of the Civil War, padrones took thousands of children from their homes in Italy and brought them to the United States. Padrones were not always abusive and certainly not all kidnappers, but the system was highly flawed and frequently brutalized helpless victims. When the war ended, Black slaves in the South obtained the freedom guaranteed by President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. But in the northern states of the Union, the exploitation of Italian child musicians endured for decades.

Most of these youngsters came to New York City, settling in lower Manhattan just north of the Five Points neighborhood. They were sent into the streets to perform for money. Every evening, the little entertainers went back to their lodgings and gave the day’s income to their masters. Those who presented inadequate earnings were severely punished.

In 1874, Congress outlawed the trafficking of child musicians. Yet, the first padrone was not convicted until 1880. Small wonder that many abused children decided to run away from their captors. Many of the refugees perished, but the most adaptable persevered. Among the survivors was Levi Malona, whose story is emblematic of many others and resonates as strongly today as it did so long ago.

On April 16, 1886, a young man entered the Castle Garden emigrant depot and, addressing assistant superintendent Otto Heintzman, said: “I want to know if you can help me to find out who I am.” Heintzman was incredulous, but as his visitor appeared sober, he asked his name.

“I am called Levi Malona,” he replied. “I know that I was born in Italy and was stolen from there when a child, and I know that the name by which I am called is not my real name. I want to find where I was taken from, and if any of my family are still alive in Italy or in this country.” The young man then told the officer his story.

About eighteen years earlier, Levi and his younger brother had been kidnapped from their home in Italy. They were transported to the United States and sold to a padrone in Lower Manhattan. Amid many whippings, the boys were taught to sing, beg, and play violin. When they didn’t bring home enough money to please the padrone, they were beaten and sent to bed without supper. After two years of this torture, Levi escaped from his master, leaving his brother behind. Fleeing the city, Levi tramped through the countryside, finally arriving at a small community in the rolling hills of western New York, where he found work as a farm hand.

The years passed, and Levi grew to manhood. Yet, he never forgot his brother. So, he returned to Manhattan, hoping to find him. Levi’s search was fruitless, but his investigation revealed that his captor had been Raffaelo di Grazia, known on both sides of the Atlantic as the infamous “King of the Padrones.”

Although Levi failed to find his brother, he was determined to secure his future. So, he filed a certificate of naturalization. In 1890, he married Antonette Rogers, and soon the couple had a son. Once a frightened runaway, the young man was now a husband, a father, and a proud citizen of the United States.

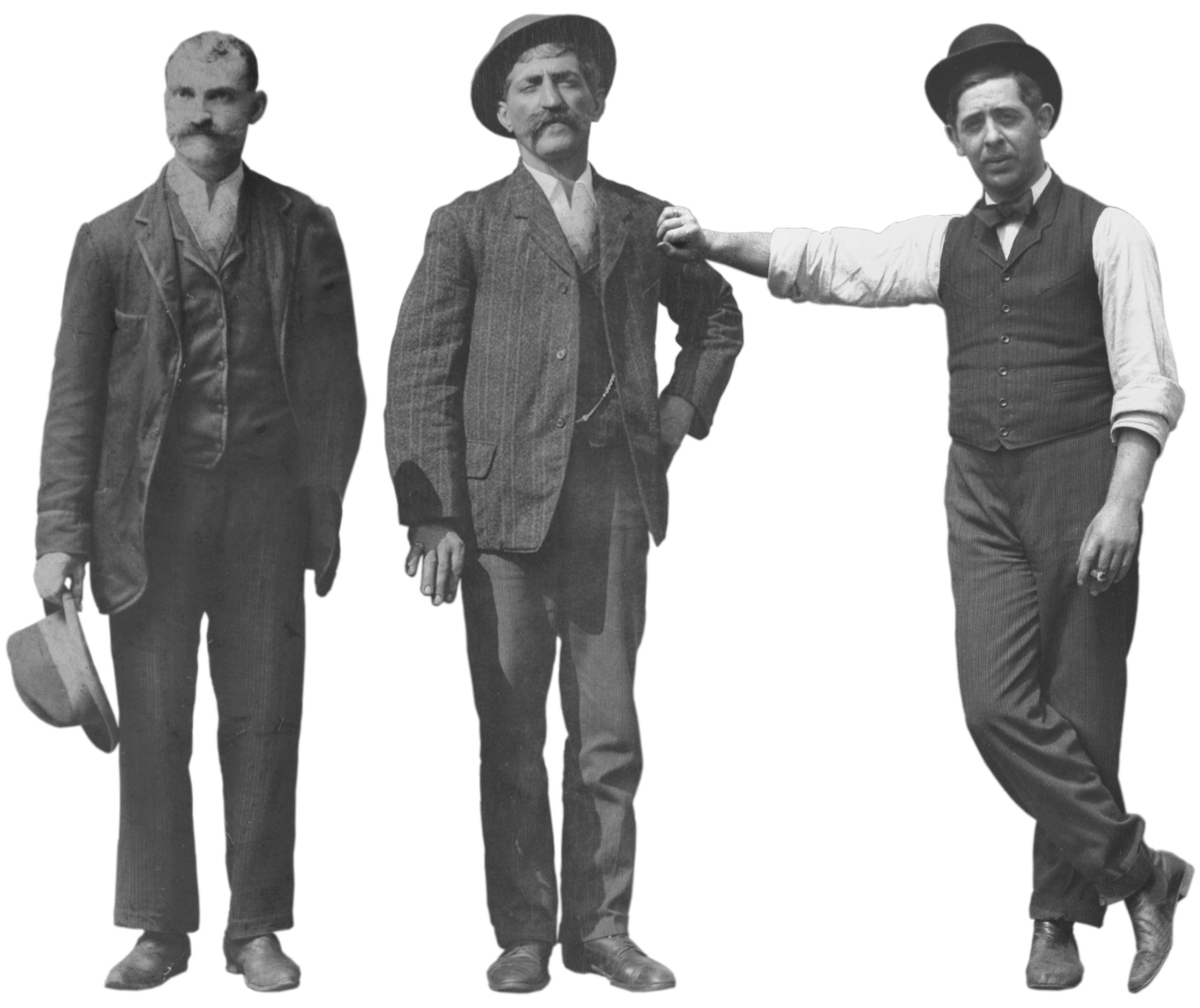

The boldest and most desperate of the Italian child musicians made daring escapes from their oppressors. Although some were caught, their fates are mostly unknown. But against all odds, a few gained their precarious freedom and eventually started new lives in America. Street smarts, tenacity, and luck enabled these youngsters to overcome the tremendous obstacles that threatened their liberty. The hard lessons of urban life had taught the little Italian musicians not only to survive but to prosper in America, their adopted homeland.