The practice of forcibly sterilizing Indigenous women in Canada is still going on.

So says a Senate report last year that concluded, “this horrific practice is not confined to the past, but clearly is continuing today.” In May, a doctor was penalized for forcibly sterilizing an Indigenous woman in 2019.

Compulsory sterilization in Canada has a documented history in the provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia. In 2017, sixty indigenous women in Saskatchewan sued the provincial government, claiming they had been forced to accept sterilization before seeing their newborn babies.

Thousands of Indigenous Canadian women over the past seven decades were forcibly sterilized, in line with eugenics legislation that deemed them inferior. The Canadian sterilization laws of 1928 created a Eugenics Board that could impose sterilizations on people without their consent. Similar laws were being enacted in other countries, the US included. The law was meant “to protect the gene pool.” This developed into a familiar practice, especially in relation to indigenous men, women and children. Numerous activists, doctors, politicians and at least five class-action lawsuits say the practice has not ended in Canada.

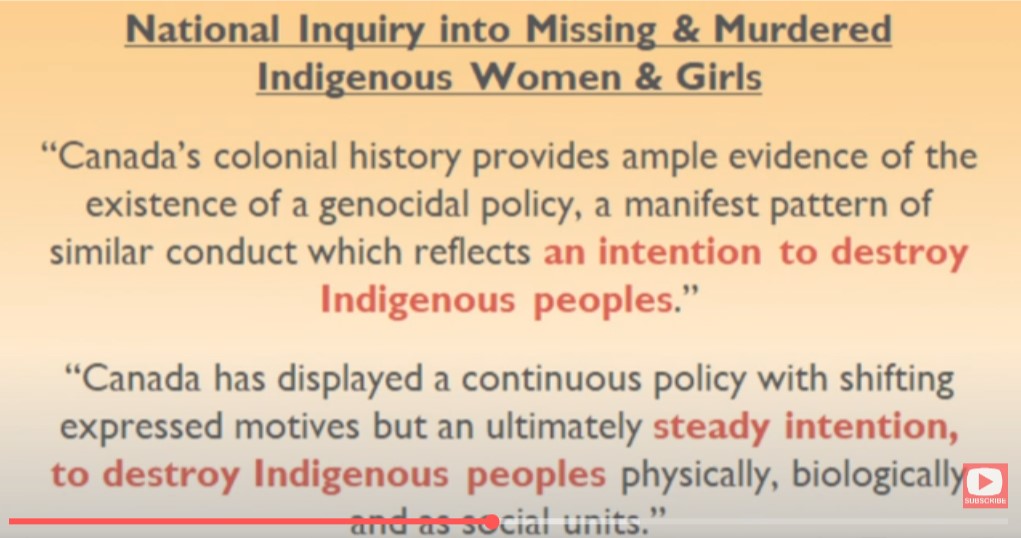

Indigenous leaders like Pam Palmater say the country has yet to fully acknowledge its troubled colonial past and its injustices— or put a stop to a decades-long practice that is considered a type of genocide.

There are no solid estimates on how many women are still being sterilized against their will or without their knowledge, but Indigenous experts say they regularly hear complaints about it.

Sen. Yvonne Boyer, whose office is collecting the limited data available, says at least 12,000 women have been affected since the 1970s. Some women were not even aware they were sterilized.

“Whenever I speak to an Indigenous community, I am swamped with women telling me that forced sterilization happened to them,” Boyer, who has Indigenous Metis heritage, told The Associated Press.

Medical authorities in Canada’s Northwest Territories issued a series of punishments in May in what is likely the first time a doctor has been sanctioned for forcibly sterilizing an Indigenous woman, according to documents obtained by the AP.

Dr. Andrew Kotaska, who performed an operation to relieve an Indigenous woman’s abdominal pain in November 2019, had her written consent to remove her right fallopian tube, but the patient, an Inuit woman, had not agreed to the removal of her left tube; losing both would leave her sterile.

Despite objections from other medical staff during the surgery, Kotaska took out both fallopian tubes, in effect depriving the patient of the right to motherhood.

The investigation concluded there was no medical justification for the sterilization, and Kotaska was found to have engaged in unprofessional conduct. Kotaska’s “severe error in surgical judgment” was deemed to be unethical investigators said.

But advocates found the outcome to be insufficient and have been fighting for the end of the practice. Pamela Palmater is a Mi’kmaq lawyer, professor, activist and politician from New Brunswick, Canada. She is an associate professor and the academic director of the Centre for Indigenous Governance at Toronto Metropolitan University. A frequent media political commentator, she appears for Aboriginal Peoples Television Network’s InFocus, CTV, and CBC to lead the protest.

There have been many previous attempts to curb the Canadian policy. In 2018, the U.N. Committee Against Torture expressed concern to Canada about persistent reports of forced sterilization, saying all allegations should be investigated and those found responsible held accountable.

In 2019, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau acknowledged that the murders and disappearances of Indigenous women across Canada amounted to “genocide,” but activists say little has been done to address ingrained prejudices against the Indigenous, allowing forced sterilizations to continue.

In a statement, the Canadian government told the AP it was aware of allegations that Indigenous women were forcibly sterilized and the matter is before the courts.

“Sterilization of women without their informed consent constitutes an assault and is a criminal offense,” the government said.

“We recognize the pressing need to end this practice across Canada,” it said, adding that it is working with provincial and territorial authorities, health agencies and Indigenous groups to eliminate systemic racism in the country’s health systems.

The Senate report on forced sterilization made 13 recommendations, including compensating victims, measures to address systemic racism in health care and a formal apology.

In response to questions from the AP, the Canadian government said it has taken steps to try to stop forced sterilization, including investing more than 87 million Canadian dollars ($65 million) to improve access to “culturally safe” health services, one-third of which supports Indigenous midwifery initiatives.

The rhetoric surrounding the issue is all above criticism and the Canadian government has repeatedly expressed sympathy for the victims and the determination to end it, but still, the practice continues.