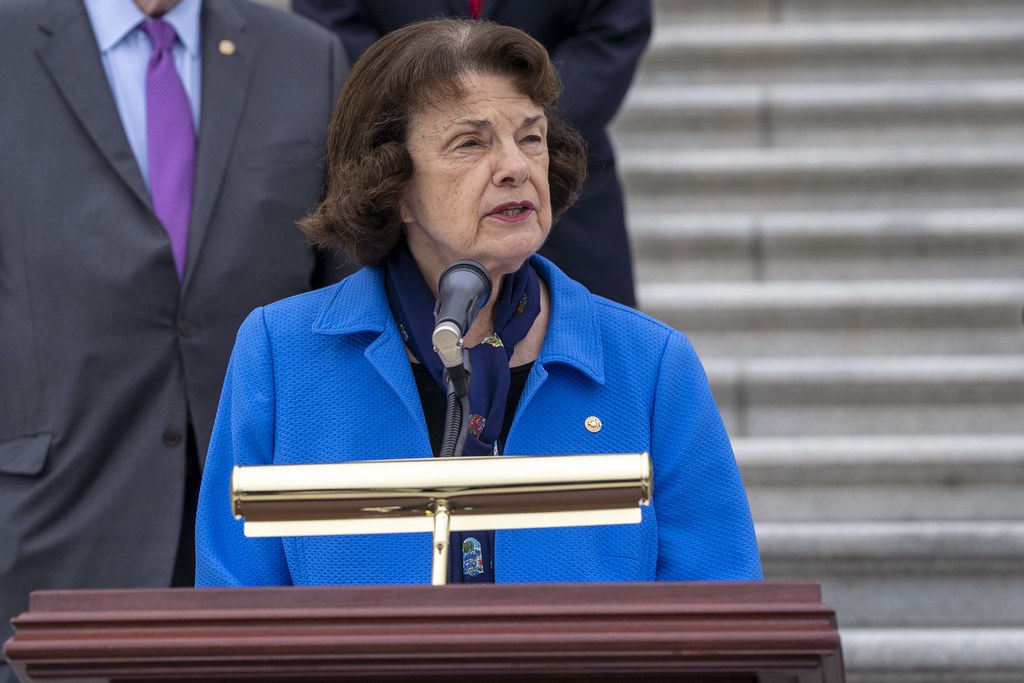

Democrats currently face a mounting crisis concerning the mental fitness of their oldest member in the Senate, Dianne Feinstein. The first public sign of her senility was on November 17th 2020 in a Senate hearing about social media, where she asked a question to then-CEO of Twitter Jack Dorsey, only to read out the same question verbatim again after receiving his answer. According to an exposé in the New Yorker from December of that year, Democratic Senate leader Chuck Schumer asked Feinstein to step down as ranking member of the Judiciary committee based on these concerns. Feinstein apparently forgot their conversation from one day to the next, forcing Schumer to go through it all over again before it sank in. “It was like Groundhog Day, but with the pain fresh each time,” according to a source.

This brings us to today, where Feinstein has been absent from the Senate for weeks and is requesting a temporary replacement on the Judiciary committee. Since this came to light three years ago, term limits have been posited as a potential remedy for this situation. On a surface level, the idea is appealing in this case because it presumably removes the possibility of someone getting too old for holding public office, but this misunderstands the problem.

We’ve already had no-show Senators, like Karl Mundt of North Dakota, who was absent for a full three years in his final term after a stroke in 1969, or Carter Glass of Virginia, who refused to resign under circumstances similar to Feinstein’s in the 1940s. Beyond these cases, it is far from inconceivable that a Senator even decades Feinstein’s junior might go through the same mental decline (or some other incapacitation) within a defined term limit, or even their first term. What is needed to put an end to cases like Feinstein, Mundt, and Glass is a statute that addresses the possibility of a congressperson’s incapacity directly. The 25th Amendment of the constitution offers a course of action in case the president in incapacitated (an office that already has defined term limits), but when it comes to members of Congress the American people have no recourse. In Carter Glass’ case, frustrated Virginia citizens eventually petitioned the courts to deal with the effectively vacant seat, but to no avail.

Another common argument in favor of congressional term limits is that long careers in Congress afford opportunities for corruption. The problem with this idea is that the length of a legislator’s time in office cuts both ways. A long career in Congress does indeed allow for corrupt politicians to damage the institution through grift and further a culture against the public interest. Senator Joe Manchin is a prime example of a politician with this kind of career, having used his positions first at the state level in West Virginia and then in Congress to further his financial interests in the coal industry, and little else. He is currently busy stymying White House proposals to reduce the usage of fossil fuels.

That said, a long career in Congress also allows those committed to doing work in the public’s interest to hone their skills in those pursuits. Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, who has been a creature of Congress since the 90s and a Senator since 2007, is using his new position as head of the powerful Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee to great effect, fostering the national conversation on workers’ rights and price-gouging by calling CEOs to testify on their practices. His power to set the agenda for the committee is sure to have ramifications going forward.

Despite the obvious conflict of interest presented by Manchin’s investments and his opportunities to use his position for their benefit against the public interest, none of that technically violates Senate rules. If corruption is what we want to prevent, then why not legislate directly against it, rather than impose term limits that cut short the careers of those dedicated to public service? (Indeed, studies largely find that term limits simply limit the legislative branch’s power, rather than rid it of corrupting influences.) Campaign finance reforms and more stringent rules on outside legislators’ investments, with serious penalties for violations to both, would go a long way in curbing the corruption of those holding public office. Passing these measures is not any more unrealistic than imposing term limits, and they cut to the heart of the issue rather than hoping to minimize the problem indirectly.