A rare gem of an exhibition, Sargent in Paris, now on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, commemorates John Singer Sargent on the centenary of his death (1856–1925) by focusing on the formative decade he spent in Paris, from 1874 to 1884 — the years that shaped his artistic vision and launched his career. Open through August 3, 2025, the exhibition will then travel to the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, where it will run from September 22, 2025, to January 11, 2026. Featuring around 100 works — oils, watercolors, and drawings — the show includes, of course, Sargent’s most iconic and controversial portrait: Madame X.

The story of Madame X is one of youthful ambition, social scandal, and artistic triumph. In 1882, a talented 26-year-old Sargent asked his friend Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau — a striking New Orleans-born socialite — to pose for him. Known for dusting her pale skin with lavender-infused powder and reddening the tips of her ears, Gautreau was as pleased with the resulting portrait as the painter himself. But when the work debuted at the Paris Salon in 1884, it caused an uproar. Critics found it indecent; Gautreau was denounced as haughty and suggestive. Her mother accused Sargent of ruining her daughter’s reputation.

The real scandal? A single dress strap, painted as if it had slipped down her shoulder, hinting at an intimate undressing. Sargent repainted the strap in its proper place, but the damage was done. The backlash prompted him to remove the sitter’s name from the title — renaming it simply *Madame *** — and eventually to flee to London, seeking to restore his reputation. Decades later, in 1916, after Gautreau’s death, Sargent donated the portrait to the Met, calling it “perhaps my best work.”

But the Met’s exhibition is not merely a retrospective of a scandalous masterpiece. It is the sweeping story of a precocious and prolific career, one that began not in Paris, but in Florence. Born there to American expatriate parents, Sargent showed early artistic promise. He sketched daily, mastered watercolor techniques at a young age, and trained at the Florence Academy of Fine Arts.

“The time he spent in Italy was absolutely crucial to his development,” explains Stephanie L. Herdrich, Alice Pratt Brown Curator of American Painting and Drawing at the Met, who wrote her dissertation on Sargent and his Italian cultural references. “He immersed himself in Vasari’s art history, studied ancient works in the Vatican, and as a child of 10 or 11, he was already copying classical sculptures. He studied Michelangelo and Tintoretto — and even analyzed Tintoretto’s studies of Michelangelo. What he did was take that classical foundation and make it modern.”

Sargent’s Italian years — from Venice to Naples to Capri — were essential to his artistic language. Before turning 18, he had traveled across the country, soaking in its culture and landscape. In Capri, he painted local beauty Rosina Ferrara draped around the limbs of an old olive tree; Greek-featured boys; girls dancing the tarantella on a rooftop. He played with the whites of shirts, rooftops, and sunlight. In Naples, he depicted four nude children playing on the beach — a work later shown at the New York Academy of Design in 1879 to great acclaim.

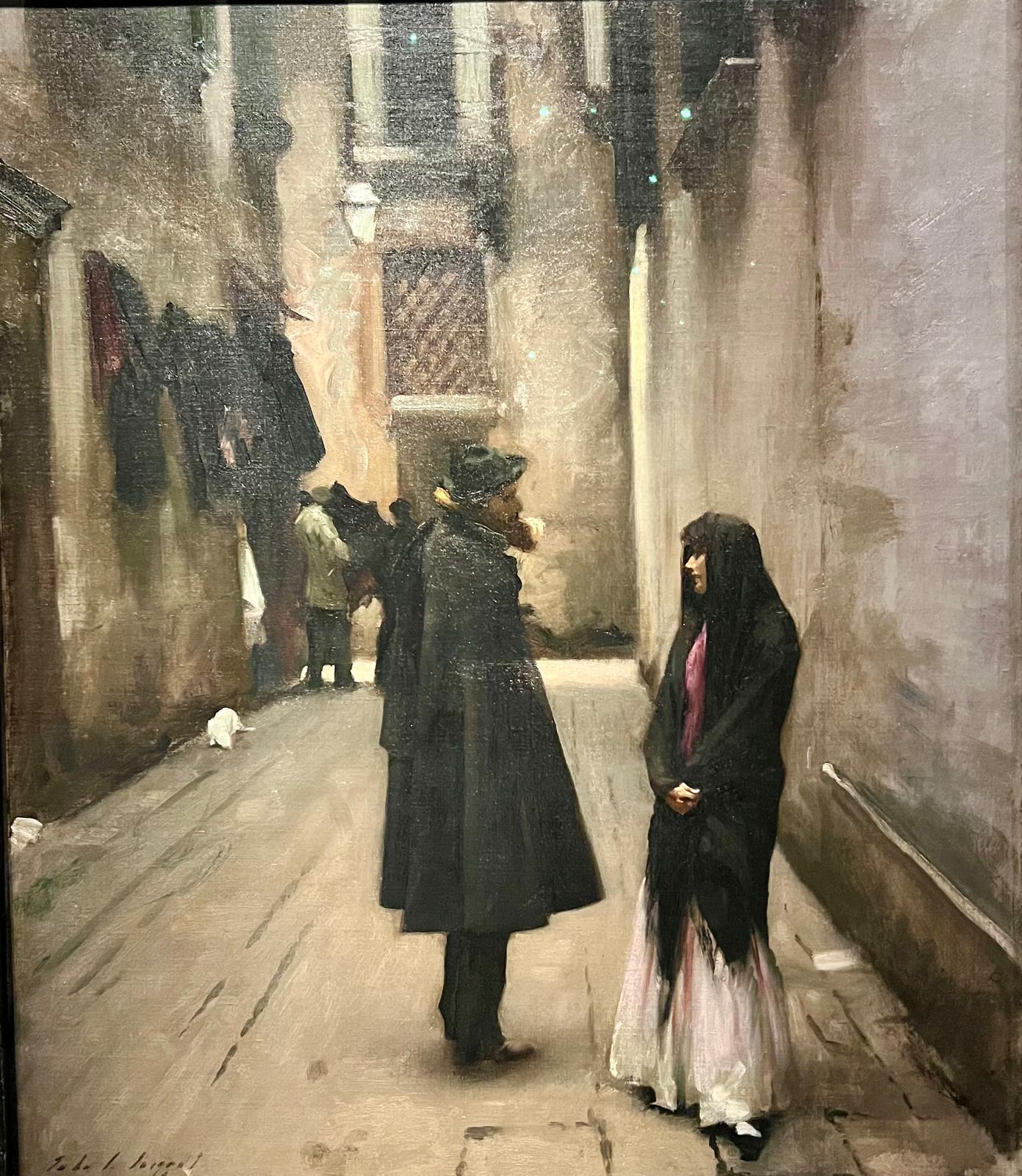

In Venice, where he stayed in 1880 and 1882, he turned his eye to shadow and atmosphere: gray canals, hazy skies, the muted tones of gossiping women in stone archways. He brought these moody works to Paris’s progressive Galerie Georges Petit.

Meanwhile, Sargent was beginning the grand portraits that would establish him as the leading society painter on both sides of the Atlantic. From Amalia Subercaseaux to Lady with a Rose (1882), which shows the influence of Velázquez, to the striking Viscountess Marie Jeanne de Kergolay (1883), where he faithfully captures her face but lets imagination run free in the crimson gown and garland in her hand — Sargent was quickly refining his signature style.

His breakthrough came with Mrs. Henry White (Margaret Stuyvesant Rutherfurd White), the first socialite to commission him in Paris. After relocating to London and displaying the portrait in her drawing room, she helped introduce him to British high society. Other sitters followed, including Mrs. Albert Vickers (Edith Foster), whose portrait opened doors for Sargent in England.

But his subjects weren’t just women of the elite. Dr. Samuel Jean Pozzi, a flamboyant Parisian surgeon and gynecologist, was immortalized in a red robe that highlighted both his hands and his sensual charisma. And among Sargent’s most painterly experiments were plein air portraits of fellow artists, such as Paul Helleu and his wife Alice Guerin (1889), painted with the technique learned during Sargent’s time with Monet in Giverny — detailed figures rendered against grass suggested with bold, impressionistic strokes.

Sargent in Paris is a portrait of an artist in motion — across borders, between eras, and at the crossroads of tradition and innovation.