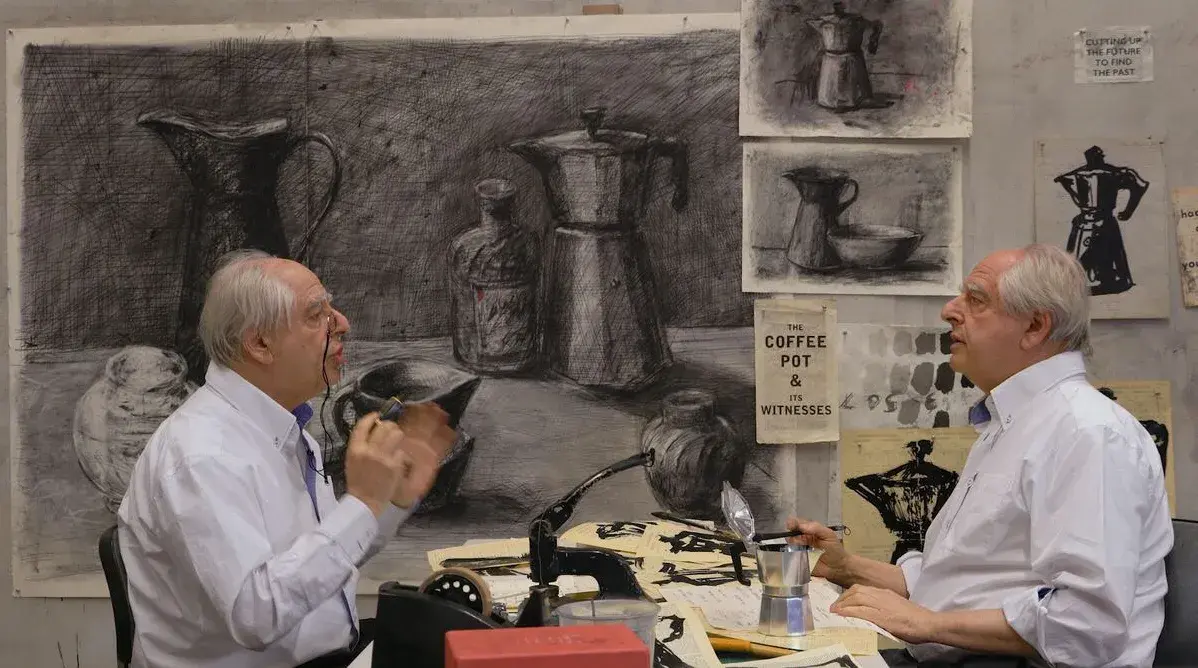

Shut yourself in the studio and draw a coffee pot. Again and again, day after day, until that coffee pot—an ordinary, domestic, harmless object—becomes a self-portrait, an avatar, the perfect excuse to tell your story without really talking about yourself. That’s how Self-Portrait as a Coffee-Pot came to life, the most recent—and perhaps the most unrestrained—project by South African artist William Kentridge (b. 1955), brought to New York by Hauser & Wirth from May 1 to August 1, 2025, with the exhibition A Natural History of the Studio.

On 22nd Street, the full film series—nine episodes shot between 2020 and 2024—screens alongside the charcoal drawings that spawned it: more than seventy works on paper that feel less like preparatory sketches and more like creatures in their own right. The studio walls become a storyboard; the artist’s workspace is reimagined—not nostalgically—as a mental workshop, where every surface is in flux. And the coffee pot? It’s everywhere: examined, debated, reimagined until it becomes a breezy metaphor for the creative process itself.

Upstairs, the drawings break free from the page. Paper Procession features figures cut from a 19th-century ledger found in a Palermo church, reinterpreted here as hand-painted aluminum silhouettes—light, compact, poised on slender metal frames that give them an uncanny mobility, as if they might step forward at any moment. Nearby are the glyphs, small bronze sculptures born from drawings and collages, translated into three dimensions where they become visual words—signs open to multiple readings, part of a mute lexicon that speaks fluently to anyone attuned to Kentridge’s language. The glyphs also appear in the video Fugitive Words, shown in the same room: notebook pages come alive, words scatter and reform, drawing tools move on their own, animating a stream of images that refuses narrative but never stops flowing, all to the tune of Beethoven’s Archduke Trio.

Meanwhile, at the 18th Street space, a selection of thirty prints made over the past two decades rounds out the show. Kentridge, who began exploring printmaking during his student days in Johannesburg, has experimented across techniques—lithography, woodcut, photogravure, drypoint—using them not just as media but as modes of thinking. There’s the 2012 typewriter, fractured portraits of Lenin, Trotsky, and Mayakovsky, and four recent self-portraits built like puzzles of marks. Sometimes, all it takes to evoke an artist is a coffee pot. As long as it’s drawn by Kentridge.