The New Art: American Photography, 1839–1910, opening April 11 at The Met, presents itself as a visual archive that, through a typological approach, explores the formation of American identity from 1839 through the early twentieth century. With more than 250 photographs—many of them on public display for the first time—the exhibition invites visitors to engage with a narrative shaped not by events, but by forms, following a curatorial logic that privileges visual structure over chronological progression.

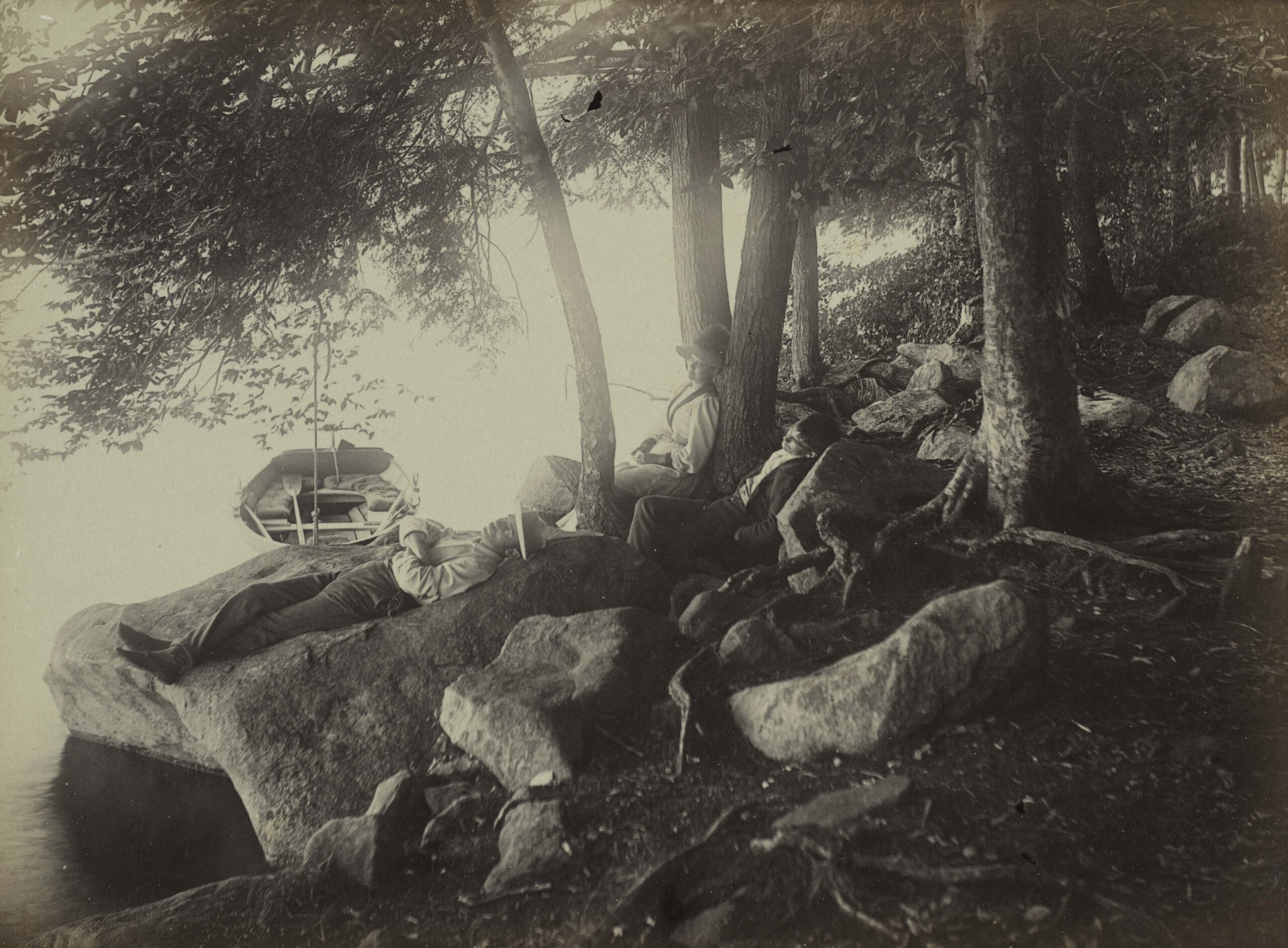

Portraits and landscapes, seated bodies, resting hands, work clothes and Sunday best form the iconographic fabric of the show. Yet it is not the individual subject that drives the reading, but repetition: postures, spatial relationships, gaps, and silences become the compositional elements through which recognition and comparison take place. Each photograph functions as a specimen—like a botanical plate in a visual herbarium—and together they delineate a carefully structured field of observation. The reference to German typological series is unmistakable: the approach is dry, deliberate, and intentionally restrained. Here, early American photography is not driven by the urgency of the authorial gesture, and the notion of the “snapshot” is entirely absent. Every image is the result of conscious decision-making, of extended duration, of a pose held still. These subjects are not caught unaware; they offer themselves consciously to the mechanical eye of the camera.

Family portraits appear alongside images of the deceased; the rigid grace of children coexists with the silent presence of African American communities; and the devastation of Native populations emerges not through emotional emphasis, but as a structural element. All of this is rendered through a visual coherence that deliberately avoids pathos in favor of precision and restraint.

Alongside renowned photographers such as Josiah Johnson Hawes, John Moran, Carleton E. Watkins, and Alice Austen, the exhibition also brings to light the work of anonymous or lesser-known practitioners, expanding the official narrative of photographic history to include a multitude of overlooked perspectives—no less significant for their marginal status. Particular attention is given to the representation of African Americans, who from the Civil War onward used photography as a tool to subvert imposed visual identities. In this context, Frederick Douglass stands out as a pivotal figure: for him, photography was a right—a means to reclaim iconic presence and self-representation. Within the exhibition, Black men and women are not passive subjects of the camera’s gaze; they are active participants in the visual dialogue, claiming their place with poise and clarity.

The same impassive gaze defines the images of rural America, growing towns, and colonized landscapes. These photographs do not narrate—they isolate. Buildings, cultivated fields, roads, bodies: everything is treated with the same analytical distance. The great ruptures of American history—Native displacement, slavery, civil war, urbanization—are not dramatized but placed in sequence, offered as visual data within a syntax stripped of rhetorical gesture.

To close the exhibition, a curated selection of nineteenth-century photographic apparatuses serves as both historical reference and methodological key. These are not simply relics of a past technology, but cultural instruments that still speak to the complexity of the photographic act in its formative years. As Jeff L. Rosenheim, curator of the exhibition, affirms, these images—“rivals to the great literature of the time”—laid the foundation for a language of vision that, despite its evolution, continues to resonate today: photography as writing, as method, as systemic construction of the real.