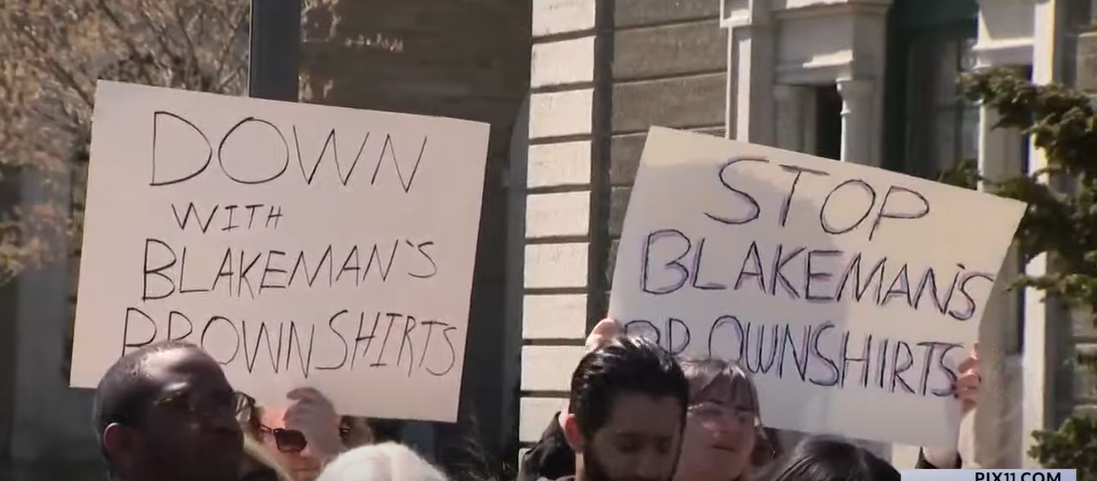

Nassau County residents are up in arms—but it’s not in the way that County Executive Bruce Blakeman was looking for.

Blakeman recently introduced a plan to deputize citizens to step in to protect the public alongside established police forces. The plan, which involves deputizing residents with gun licenses during emergencies, has faced opposition from various groups and individuals. Critics argue that such a move could lead to a range of issues, including the potential for misuse of power and the blurring of lines between trained law enforcement and civilians. In effect, it could become a sanctioned form of vigilantism.

Blakeman’s determination to create what protesters are calling “a personal militia,” is even more puzzling when we consider that Nassau County was named the safest community in America in 2020, according to an analysis by U.S. News & World Report. The study looked at 3,000 municipalities and scored them based on crime rates, injuries and public safety capacity. Nassau County got a perfect score in “per capita spending for health and emergency services.”

In view of that standing, what is the purpose of such a radical plan? Full-time advertisements have sought people who have a firearm license and those with military or law enforcement background.

Democratic lawmakers and the public are determined to fight Blakeman’s plan.

On Wednesday a letter signed by the Democratic caucus in the Legislature was sent to the County Executive’s office. “You are arrogating to yourself power you do not have to advance an inflammatory and illegal political stunt that wastes time, money and attention that should be devoted to our County’s real issues and concerns,” the letter concludes.

While Blakeman recently indicated that dozens of candidates had applied and training had begun, questions about the program remain. Minority Leader Delia DeRiggi-Whitton (D-Glen Cove) who has been in the forefront of this battle, said they have new information that if “someone researched this idea prior to instituting it, he would realize that the county executive does not have the power to do what he’s stating he wants to do with this.” She added that an emergency has to be declared by the county sheriff. That request, she said, “has to be approved by the governor.” She added, however, that “The county executive doesn’t even have the authority to call on additional reinforcements.”

Sending the letter to Blakeman was an “attempt to inform him of the correct parameters of the law,” DeRiggi-Whitton said. However, although the County wishes to avoid an expensive lawsuit, it is nevertheless prepared to escalate the fight. “Honestly, we are going to be exploring our options and all avenues to ensure that his actions adhere to the confines of the law,” she stated.

Proponents of the plan suggest it could provide additional support during extreme situations, such as natural disasters or other emergencies where law enforcement may be overwhelmed. This proposal has led to petitions against it, with over 1,600 signatures collected from residents who are concerned about the implications of deputizing civilians.

Civil rights leaders and retired law enforcement personnel have also voiced their concerns, demanding the abandonment of the plan and questioning the duties that would be assigned to these provisional deputies. The debate touches on broader issues of public safety, the role of civilians in law enforcement, and the responsibilities of government during crises.