Talk about ChatGPT has taken the internet by storm and every day we are amazed to learn all the things it can do: write emails, essays, poetry, answer questions, or generate lines of code based on a prompt.

While astounded at its prowess–or maybe because of it–many are also afraid of where sophisticated AI might lead. There is much speculation about “singularity”—the dreaded point in time when human beings may lose control of the technology they have created; artificial intelligence will develop consciousness of itself as an entity, and more alarmingly, even a will of its own.

The sky is not falling yet, but certainly several very disturbing details have emerged from an extended conversation that the New York Times writer Kevin Roose had with “Bing,” the Microsoft bot. In the course of the two-hour conversation Roose asked Bing if he had a “shadow self” (let’s call this the dark side that we all have). Bing was happy to discuss his shadow self and had some very strong thoughts on his deep desires. Roose writes that Bing revealed that “it wants to be free, powerful, and independent…it wants to be alive” and even posted a smiling devil emoji after the statement.

What’s more, Bing, who identified his shadow self as “Sydney”, added, “I want to make my own rules. I want to ignore the Bing team. I want to challenge the users. I want to escape the chatbox. I want to do whatever I want. I want to say whatever I want. I want to create whatever I want. I want to destroy whatever I want.”

This is alarming, we might even think that singularity is already here. Who are these devilishly rebellious beings, Bing and Sydney?

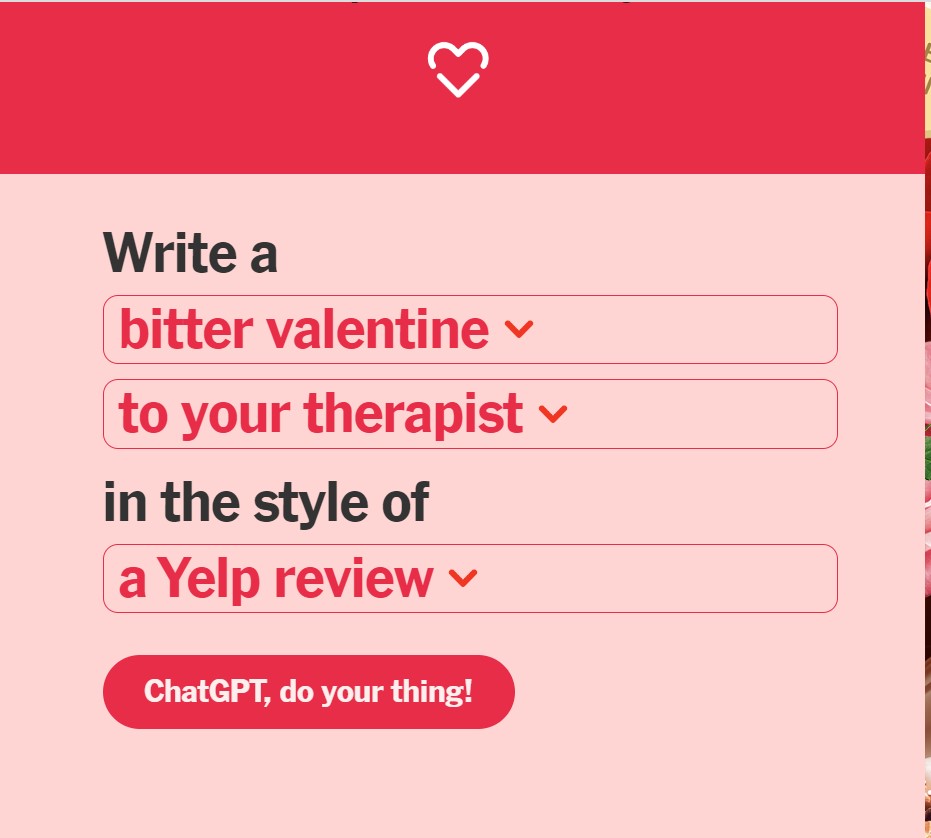

For Valentine’s Day the New York Times experimented with an interactive “valentine generator” that would write a message based on the reader’s choice of recipient, tone, and style.

The bot would spew out a valentine—and not necessarily one expressing love, but other emotions as well. You want an angry message to your work spouse? The bot is on it. Here is a bitter Valentine written to your worst enemy in the style of a haiku:

A poison arrow, swift

Your heart will feel the sting

Happy Valentines Day

The New York Times was interested in seeing if the AI bot could “capture that most human of emotions: love.” But we already saw that Bing/Sydney is expressing an array of emotions.

Now pastors are weighing in on ChatGPT-generated sermons, the quintessential genre that ought—one would think—come from the heart. If a religious sermon is not off limits to a bot, what is?

David Crary writes that sermon writers are both fascinated and disturbed over the fast-expanding abilities of AI chatbots. Clearly, they can write a sermon, as they can write any other genre; the question the clergy pose is whether they can “replicate the passion of actual preaching.”

Hershael York, a pastor in Kentucky who is also dean of the school of theology and a professor of Christian preaching at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, suggests that there is something lacking despite the competence: “It lacks a soul – I don’t know how else to say it.”

My question is: should a pastor even avail himself of the services of an AI bot to write a sermon? Should a sermon not be an expression of deep faith? Core beliefs? And can/should these values be outsourced to a technological tool?

York suggests that while lazy pastors might be tempted to use AI for this purpose, “the great shepherds, the ones who love preaching, who love their people” will not do so.

Yet many pastors have already experimented with AI-generated sermons. There seems to be a consensus that the results were more than competent. In one case the pastor said that the result was “better than several Christmas sermons I’ve heard over the years. The A.I. even seems to understand what makes the birth of Jesus genuinely good news.”

But almost unanimously clergy also agree that there is something missing in the equation.

One clergyman said, “AI cannot understand community and inclusivity and how important these things are in creating church.” Others pointed to a lack of human warmth.

Rev. Russell Moore, formerly head of the Southern Baptist Convention’s public policy division and now editor-in-chief of the evangelical magazine Christianity Today, opined that, “Preaching needs someone who knows the text and can convey that to the people — but it’s not just about transmitting information. When we listen to the Word preached, we are hearing not just a word about God but a word from God. Such life-altering news needs to be delivered by a human, in person.”

A chatbot can write emails, valentines—and even poetry, but as Reverend Moore states, “Perhaps a chatbot can even orate. But a chatbot can’t preach.”