Panettone is a national joke in Italy—much like fruit cake in the UK and the U.S., it’s the gift that keeps on giving as each recipient regifts it to the next, wanting nothing more than to get rid of it. Or at least, it was until recently.

But in the last decade, the Christmas classic has become wildly popular outside its Italian borders and gained a global profile. Like Basque burnt cheesecake and French croissants, as panettone is being adopted it is also being transformed into new incarnations with unprecedented flavors like black sesame, Aperol spritz and cacio e pepe. There are Japanese versions leavened with sake lees and Brazilian ones stuffed with dulce de leche; supermarket minis that cost $2 and truffled ones that fetch nearly $200. It has truly gone global.

At its origin, most likely in 15th-century Milan, panettone was a domed sweet bread with a tender, bright-golden crumb, scented and studded with candied fruit. It belongs to the same luxurious holiday tradition as German stollen, Polish chalka and British fruitcake: treats made once a year from expensive stores of butter and eggs, refined flour and sugar, spices from Asia and preserved fruit from the Mediterranean. Bits of chocolate were added later, and regional ingredients like lemon on the Amalfi coast and hazelnuts in Piedmont.

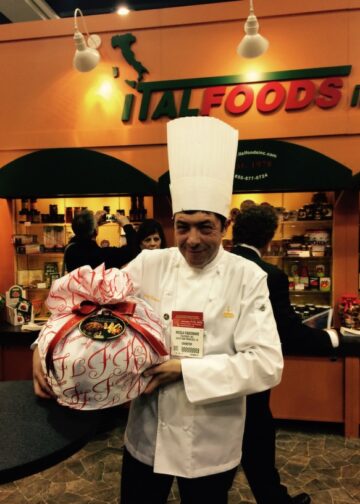

As Italy unified, panettone became a national symbol of Christmas; extravagantly wrapped and ribboned loaves became status symbols and popular gifts, but once it became commercialized its quality declined and it lost its prestige. Its subsequent ubiquity led to its demise though it continued as a symbol of the holiday.

The global attention that panettone is receiving now is also leading to new conflicts among those who make it. Disputes have broken out between purists and ultrapurists, between traditionalists and modernists, and between Italy and the rest of the world. The battles have played out in trade unions, legislatures and online, where a passionate worldwide community of sourdough bakers weighs in on matters like hydration, acidulation and almonds vs. hazelnuts.

Laura Lazzaroni, a journalist and bread consultant, said panettone is following the arc traced by pizza: A food not considered particularly interesting at home that catches on abroad, is adopted by foreign artisans, then returns to great fanfare that reinvigorates it.

“We never fell out of love with pizza, but we didn’t think about it very much,” she said. “Then people started coming home from America saying, ‘I had better pizza in California than in — insert name of my town in Italy here — and we have to do something about it.’”

Now that panettone’s reputation has risen, so have the stakes for Italian bakers, who are jockeying not only for ownership of that tradition, but also for market share. Conpait, the pastry trade group, estimates that market will be about $650 million this year, with 10 percent growth of “artigianale” over “industriali” products. Best-of lists, awards and contests like the new Coppa del Mondo del Panettone have proliferated.

The struggle to control panettone has been raging for 20 years, since Italian exporters sounded alarms that foreign-made versions were capturing the global market. Panettone has long been popular in Argentina, Peru and Brazil, where Italian food arrived along with immigrant populations in the late 19th century. Many of the panettone sold in U.S. supermarkets are made in South America, especially by the giants Bauducco and D’Onofrio.

Producing it is known as a notorious challenge. “It’s the most difficult product to make,” “Panettone isn’t a recipe; it’s a lifestyle.” Iginio Massari, a nationally revered master in Brescia (his panettone is called simply, “L’immortale,”) said it takes 10 years to train an employee to make it correctly.

High-end pastry shops and design houses like Gucci and Fornasetti have long dominated the world market for artisanal panettone. Now smaller artisan bakeries are trying to elbow in, with popular flavors like Nutella, prestige ingredients like Belgian centrifuged butter and Madagascar vanilla beans, and new techniques. Olivieri 1882, in Vicenza, makes not only its prized classic but also a limited “super classic,” with three doughs and a four-day fermentation. Infermentum, in Verona, folds in candied orange and lemon pastes along with the traditional bits of peel.

“Panettone is a perfect example of how Italian taste is always traveling back and forth, being contaminated and then reborn,” Lazzaroni said. “It would be wrong to see it as something that belongs only to us.” Apparently, it belongs to the world.