Antony and Cleopatra, the new opera by John Adams currently running at the Metropolitan Opera House, is intense. The orchestra, conducted by the composer himself, is relentless: brass, percussion, and cymbals build a dense sonic landscape that leaves little room for melody. The singers — amplified to rise above the orchestral mass — are superb: Julia Bullock and Gerald Finley command the stage with remarkable vocal and dramatic presence.

Sets, costumes, projections, chorus, and dancers combine into a powerful staging. Yet both the music and the libretto are demanding. For the first time, Adams takes on the role of librettist, following previous collaborations with Alice Goodman (Nixon in China, The Death of Klinghoffer) and Peter Sellars. He opts for a direct adaptation of Shakespeare, with a literary addition from Virgil. The result is rich and elevated, but the complexity of the language makes it difficult to follow — especially when paired with a score that never slows down.

This is not the first attempt to adapt Antony and Cleopatra to the opera. Samuel Barber tried it in 1966, but after just eight performances at the Met, the production was withdrawn. Critics blamed Franco Zeffirelli for overwhelming the music with lavish staging, but even Leontyne Price’s legendary voice couldn’t save the work from lukewarm reception.

Adams now presents his version following its 2022 premiere in San Francisco and a 2023 revival in Barcelona. He has trimmed twenty minutes from the original three-hour score, but the opera still feels long — because it rarely allows itself to breathe. The music hammers on, the narrative rushes through: Egypt, Rome, passion, betrayal, ambition, the Battle of Actium, defeat, and the double suicide. With such dramatic and musical density, there is little space left for emotional resonance, for duets, arias, or reflection.

There are, however, moments of great beauty: the duet O love between Antony and Cleopatra before the battle, the orchestral interlude inspired by Wagner’s Rheingold prelude, and Octavia’s heartbreaking aria (a standout performance by Elizabeth DeShong). Yet overall, the repetitive phrasing and relentless rhythm suggest the music is there more to propel the narrative than to illuminate it.

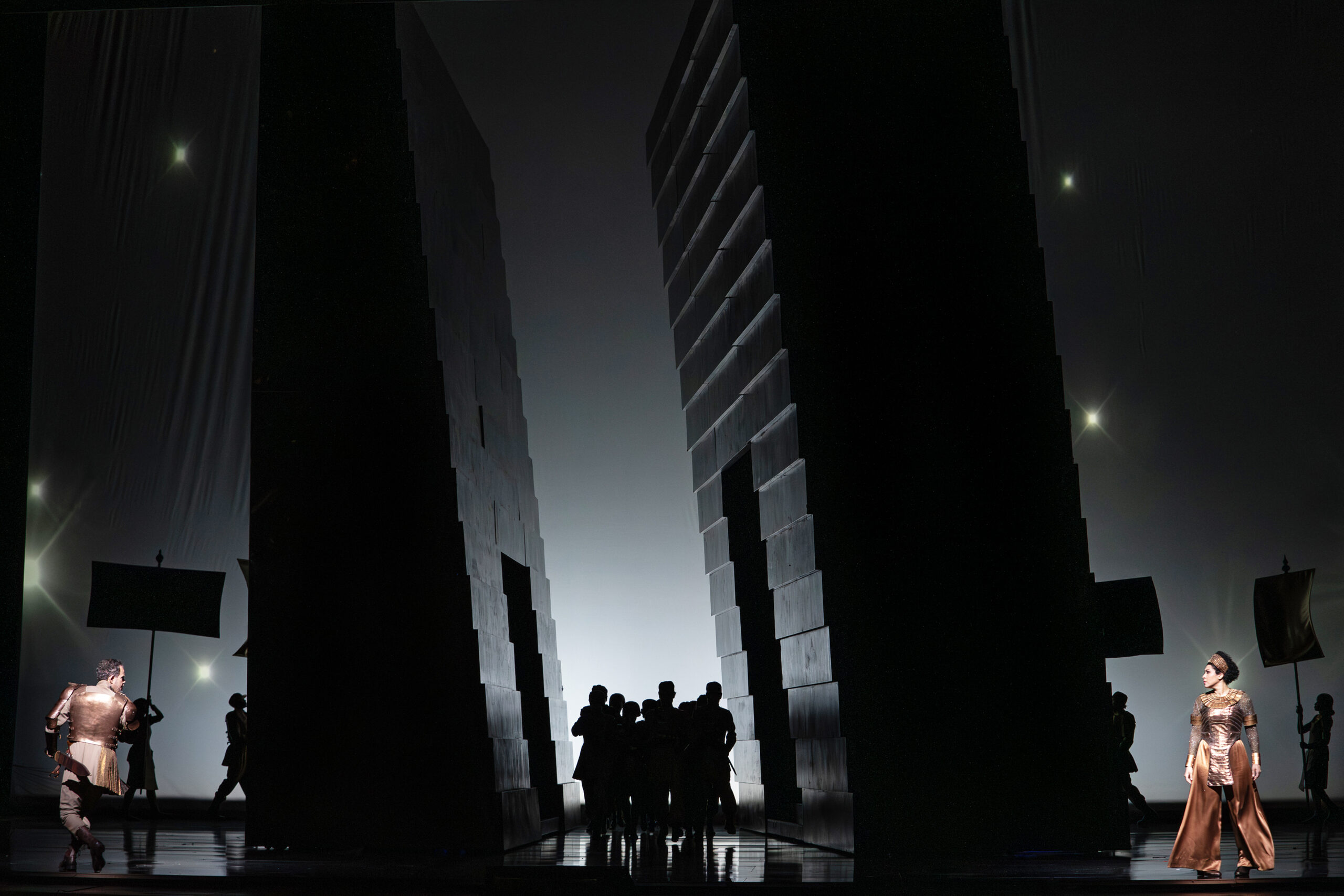

Elkhanah Pulitzer’s direction is visionary. With set designer Mimi Lien, she creates a world that blends Ancient Egypt with 1930s Hollywood and Fascist Rome. Mobile black panels morph into a pyramid, Octavian’s office, and the balcony from which he addresses the crowd — all enriched by Bill Morrison’s black-and-white archival footage (though the use of St. Peter’s Basilica to evoke Fascist Rome feels like a questionable choice). Gold dominates the triumphal scenes. Antony and Cleopatra are imagined as divine Hollywood icons, chased by paparazzi — a redundant touch.

Constance Hoffman’s costumes mix sheer fabrics, peplums, and military uniforms, bridging eras and aesthetics. Egypt becomes Art Deco. Annie-B Parson’s choreography adds visual texture, with dancers evoking both ancient bas-reliefs and goose-stepping soldiers.

All singers — even in secondary roles like Alfred Walker (Enobarbus), Jarrett Ott (Agrippa), and Taylor Raven (Charmian) — are of excellent caliber. But the stage belongs to Julia Bullock: regal, intense, and dramatically compelling. Her scream at Antony’s death is chilling. Her Cleopatra, visually echoing Elizabeth Taylor in Mankiewicz’s 1963 film, captivates the audience. Her chemistry with Finley is impeccable — from early sensuality to final fury, both embody actor-singers in full.

Paul Appleby is also excellent as Octavian, gaining prominence through a monologue adapted from Anchises’s speech in The Aeneid, envisioning Rome’s imperial destiny — a refined addition, providing the tenor with a custom-made aria.

Antony and Cleopatra is a visually majestic production, full of inventive staging and world-class performers. But the libretto and score, though sophisticated and structurally solid, fail to convey the emotional complexity of Shakespeare’s tragedy. A remarkable intellectual construct — that, ultimately, does not move.