When the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and many U.S. museums, were founded back in the 1800s, the U.S. was home to many families who came into new wealth and who began to collect beautiful works of art. These collectors and museum founders were determined to compete with amazing European collections and didn’t merely want to compete but surpass the significance of the older museums in Europe. This culture of aggressive competitiveness in acquiring artworks became the institutional cultural norm of U.S. art museums.

Not surprisingly, this institutional culture of aggressive collecting led to some cases of abuse and the acquisition of art objects that had illicit natures. In the 1970s, this peaked, and many U.S. museums and collectors bought artworks and antiquities from some of the shadiest art dealers in the world. The same names of these unscrupulous dealers came up in the numerous investigations into illicit works of art over the last 30 years.

The Met has had to come clean many times as a result of these investigations, such as the Morgantina Silver horde and the Euphronios Krater that it had to repatriate to Italy back in the beginning of the 21st century. Italian Carabinieri and Italian prosecutors proved that the Morgantina Silver, a 3rd century BC silver treasure, was illegally excavated from Morgantina, Sicily and they had concrete proof that the Euphronios Krater, a Greek masterpiece from 515 BC painted by a Pioneer Master named Euphronios, was looted from an Etruscan tomb in Cerveteri, Lazio.

Right up until this year, the Met has had to deal with its past, which is continuing to haunt it. A very diligent and aggressive Assistant District Attorney in Manhattan named Matthew Bogdanos has continued to hold the Met and other museums and collectors accountable for their past greedy culture over the last couple of years. Bogdanos heads the Manhattan DA’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit. In 2022, this unit returned 27 artifacts that were seized from the Met, to Italy, worth approximately $19 million. Italian investigators in the Italian Carabinieri Tutela Patrimonio Culturale linked these artifacts to unscrupulous dealers who trafficked them out of Italy.

Back on May 11, 2023, the Met Museum declared that they were forming a group of four provenance researchers who will work alongside curators to “broaden, expedite and intensify our research into all works that came to the Museum from art dealers who have been under investigation.” The Museum also formed a panel of 18 art experts and curators to review collections policies and practices, concentrating on artworks that were obtained from 1970 through 1990.

Met Museum Director Max Hollein stated to Agence France back on Sept 28, 2023, that the Met has developed new policies on identifying objects that left countries illegally. Hollein declared, “We don’t want to have any object in our collections that came illegally. You will see and hear from Met Museum not only about more outcome from our research but actually more restitutions, more returns and more collaborations with those countries.”

Institutional culture reflects the values of the institution and can be observed in the ethical behavior of its employees and board members. When an institution has a culture that is not worthy of respect and is based on dishonesty and greed, it often takes a major or traumatic event to cause a paradigm shift in that culture. It appears that after the multiple major events over the last decades– that is, investigations, law enforcement seizures and returns–the Met Museum is taking significant steps to move forward in an honorable direction. This is on the heels however, of another case in which the Met is being sued by the family members of a Jewish collector for a Van Gogh painting they allege was looted by the Nazis and was bought by Met Museum officials back in 1972.

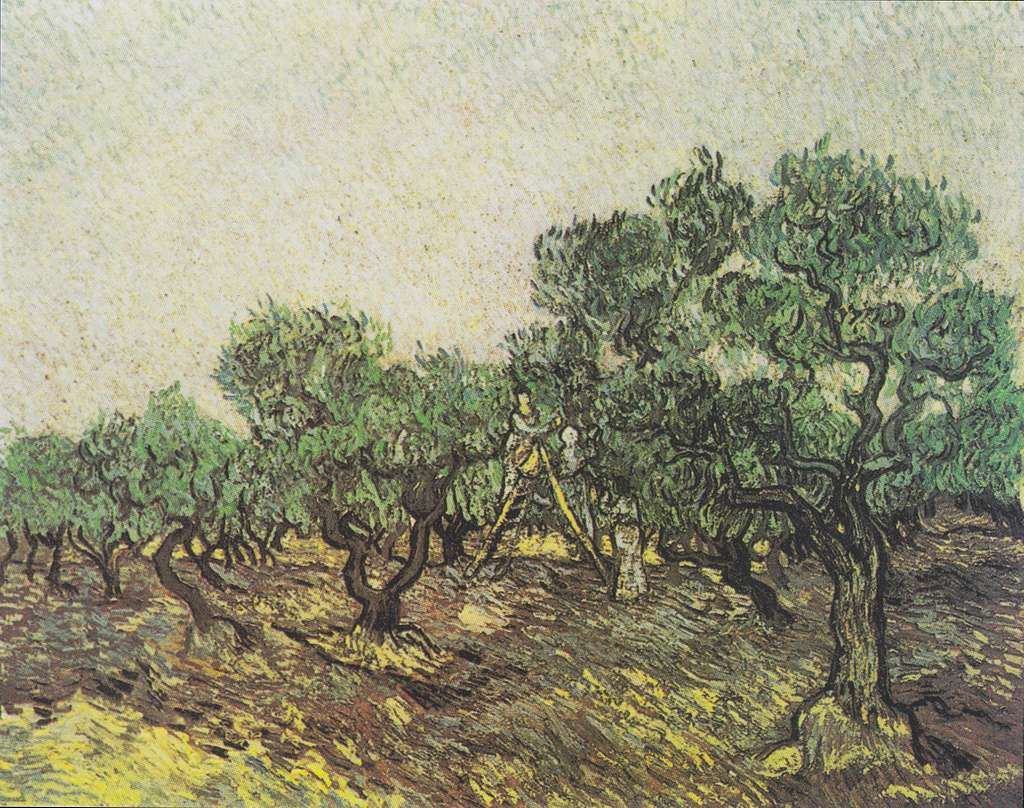

The heirs of Hedwig Stern filed a lawsuit in California contending that Stern and her husband fled Germany in 1936 and moved to California to escape Nazi persecution. The Nazis prevented them from bringing their art collection out of the country, so they were forced to sell all, including Vincent van Gogh’s Olive Pickers. The family alleges in their lawsuit that after the Met determined the artwork had an illicit provenance tied to Nazi art looting, it secretly sold the work for $70 million. It is now on view in a museum in Athens that is run by a foundation of the family that purchased it from the Met.

Artistic and historical patrimony are part of the soul of Italy—indeed, f any country. The Met is the greatest art institution in New York but for Italians there is much in its history to resent. Times change and so can institutions, and we should give them the credit for working towards a more virtuous future while remaining ever watchful. We are waiting patiently for the paradigm shift.