Nowhere-Now Here is Fulvio Testa’s watercolor exhibition title, running at Victoria Munroe Fine Art until October 29th. As the title suggests, it is a philosophical exhibition that invites meditation on the landscape and on that “non-place” where the pandemic has dragged us.

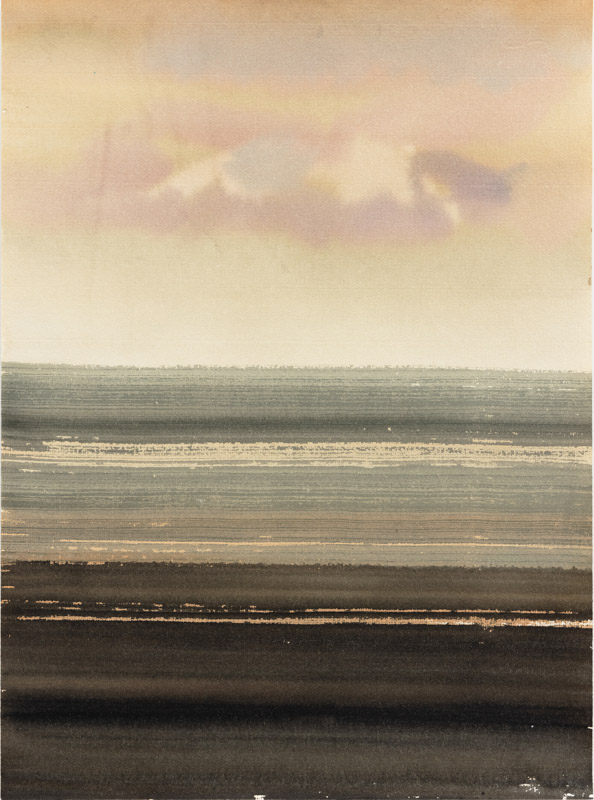

What’s on exhibit are evocations of landscapes. Not specific landscapes, but rather mental landscapes, reduced to the bone: Earth, sky, a suggestion of hills and clouds. The challenge consists of depicting interior landscapes, or universal landscapes, that resonate with all of us everywhere.

Each watercolor is a primordial wasteland, empty with no trace of human presence, yet radiant and full of potential. In a series of twenty-three works, each similar in technique and size, the recurring theme is explored in different and specific ways through light, color, density, and transparency. Testa’s technical mastery translates into essentiality and a luminous simplicity that summarizes the idea of the landscape from the eighteenth-century watercolor to the digital image.

FT: My last solo show in New York was in 2012; since then, the galleries, scene, and the art world — like the world at large, have changed a lot. I’m happy to exhibit with Victoria Monroe, someone I respect a great deal. She showed some of my work35 years ago when she had a gallery in Soho. I participated in a group show there.

After that, she moved her business to Boston, and I began exhibiting with other galleries in New York. Then, three years ago, we met again, and she still liked my work, so this is how this new show came about.

AC: The world has changed, but you have remained faithful to the theme of the landscape, declining it in myriad new ways.

Landscape, as I understand it, is a philosophical theme. Over time, apparently, the painted landscape was supplanted by photography. But the photographic landscape is something much more “current,” “concrete,” while I am interested in the idea of the landscape. After Minimalism, forty years ago, there was a return to the landscape, to a particular type of landscape, while for me, it has always been a central theme.

Can you be more specific about the type of landscape you are interested in? Each watercolor in the exhibition seems to offer to view both a form of figurative image and an abstract one.

There were times when what I painted had more abstract characteristics and others less. But it is crucial to keep in mind that what I paint are mental landscapes. They are always made in the studio, never from life. They are the distillation of observation. The landscape is, for me, everything that surrounds us.

The feeling looking at one, then another, then two next to each and all of them together is that you are painting the void. Therefore, the landscape is a spatial dimension, naked, without vegetation, and without human presence. Not specific landscapes, but rather the idea of landscape as a place we visit with our eyes.

You mentioned emptiness, the void… Emptiness is closely linked to the concept of space. In my work, I try to define the sense of space. I do this by suggesting a horizon. In common parlance, by the horizon, we mean the future. In space, the horizon is that distant line we try to reach with no chance of success.

he horizon, in your works, is the core: the line that separates and defines the Earth from the sky.

There is a story by a writer whose name now escapes me in which the son asks the father, “what is utopia?” And the father: “Utopia is that line we see in the distance. It’s called the horizon, and we need it to understand what life is.”

But as one travels ahead,” says the son, “it seems that that line, that horizon is always in the same place. “And the father,” That is true, but one must travel ahead. Utopia motivates us to travel on, to explore.”I find this story beautiful: it starts from a question that has no possible satisfactory answer and teaches us something.

We are used to thinking of landscape as a horizontal expanse. Your exhibition, on the other hand, features a majority of vertical works. For me, the vertical ones evoke gazing out from a window.

That’s right! My choice of vertical formats is, linked to an idea of a window on the landscape, a limited vision of the landscape itself. It is not an “endless” space or land that expands as far as the eye can see, but a space defined by the size of the paper. Furthermore, my rendering of the terrestrial landscape, with continuous brushstrokes that form lines, is linked to the vision of painting in modernity, where flatness is taken into consideration. From Cézanne onwards, we have been bewitched by the concept of the flat space, that is, by suggesting a space that does, in fact, not exist.

The horizontal works, unlike the vertical ones, are presented with a passe-partout. Is there a reason for this?

The fact that the vertical ones are without passe-partout was a choice of the gallery, to which I have no objection. But in truth, I have always exhibited my drawings and watercolors in the classical way, with a passe-partout. Several considerations converge in this habit of mine. Francis Bacon, for example, had the idiosyncrasy – some would say the mania – of presenting his oil paintings under glass, which is contrary to what has been done for centuries. I unconsciously feel to have embraced this idea of his, which somehow leads back to the window. Glass is a closure between what is imagined and what is visible. For me, the use that I make of the passe-partout for my works on paper is a counterpart to the use of glass by Bacon. It’s a form of framing the work it’s like putting something precious into a case

Your works seem to lend themselves to several different readings. One can privilege the abstract aspect and see them as fluctuations in density and transparency, shades of color, and pure form. Or, one can be seduced by the intimation of Earth, sky, clouds, and hills in the distance … Or further, and here it becomes more interesting, accept both suggestions.

I want to allow the viewer to imagine things beyond what I see in it. Watching is always an interpretation.

In 1978, during a rather adventurous trip to South America, I spent time in the Amazon. Back in Italy, I made a series of engravings, which I titled Bestiario Vegetale (Plant Bestiary). This is because when I was surrounded by the dense vegetation and giant trees of the Amazon, in the nearly total absence of human traces, the vegetation took on the appearance of animals and imaginary creatures. Naturally, this happened only in my imagination. Similarly, I am open to the fact that those who look at my landscapes can see in them hills, mountains, houses, clouds, or just brushstrokes and abstraction.

If I’m not mistaken, most of the exhibition was conceived during the pandemic. Although it is the continuation of an artistic research that has evolved over the years, one gets the impression that this work is your response to the specific needs and urgencies awakened by living in lockdown and being forced to reflect on what was going on.

Absolutely. They are works conceived during a period of isolation and probably reflect it at some level. But there are other elements to take into consideration as well. For example, a sense of aridity and impending desertification. A few years ago, some new images of Mars began to circulate. When I saw these images taken by robotic devices appeared in scientific magazines and newspapers, I was struck by the deserts of Mars. They are not that different from the deserts I have visited in the Southwest of the United States and in Africa. So my work took on a possible double reference: on the one hand, something that has already happened (the paralysis caused by the lockdown), and on the other, the fear of the ongoing desertification, which we do not know what it will lead us to.

Dystopian omens?

Perhaps so, but not only. To return to what I was saying about Mars, G.I. Gurdjieff thought that the planets that we see lifeless were once like our Earth, then after a great destruction, it all ended. He said we are destined for the same end.

I believe the artist never does something completely abstract. The concept of artistic creation rejects the limit, the univocal reading; at least for me, it is always open to different readings. People unfamiliar with the creative process tend to limit its scope, thinking that a given image “means” a specific thing. But think, for example, of Picasso. Often in his works, he starts from something, arriving—after ten or ten thousand stage— to something completely different. So when I am asked, “what did you want to do?” I find the question absurd.

How would you define your creative process?

It’s a bit like in the shamanic traditions; I put myself at the service of creativity rather than “using” creativity for a goal. Creativity is a word that I don’t like, but in some cases, one has to, for lack of an alternative. Art is too big a word, and decoration has taken on a very restricted connotation. Historically, decoration, craftsmanship, and art were often aspects of the work of the same individual.

Daniel Hopfer was a German artist who invented etching at the end of the fifteenth century. He lived by making armor for Maximillian of Habsburg. While decorating the armor, he realized that his decorative technique could then be used for another kind of artistic expression. He made some engravings for himself independently of his “day job” as an armor decorator. Although he is considered among the most important artisans /armor decorators, his technical intuition was the basis for the technique we call etching, which is an artistic practice that has accompanied us for centuries.

Definitions often limit rather than illuminate artists’ work; they end up being a cultural filter, a way of reading…

Yes, and it’s our fault alone. In nineteenth-century Paris, Honoré Daumier was considered an artist by many of the great artists of his time. Today, despite hundreds of sculptures, paintings, lithographs, and drawings, he is only thought of as a caricaturist. As you said, It is a cultural filter, a way of labeling.

Tell me about watercolors. After all, most ancient painting, that of the caves, was made from water and pigment… What has changed from pre-history to modern watercolor?

Primitive men mixed ocher with water, yet the watercolors as we know them, first appeared in late 1600 England. Modern watercolor differs from other forms of water painting quite sharply. It allows us what, for example, tempera does not allow.

You mean transparency?

Exactly, alternating transparency, and density. Many more ancient techniques are similar to watercolor but do not have those characteristics. More than a thousand years ago, the Chinese created something like watercolors, but not exactly. Only by the end of the seventeenth century, the British created modern watercolor. British watercolor factories supplied the goods to everyone allowing the techniques to spread and be employed in various ways by artists from different countries and traditions.

It looks simple: watercolor, water, brush, and paper …

The watercolor always has paper as a counterpart. If the paper is not good, the watercolor cannot be employed to its full potential.

You also paint with oil, but h watercolor has been with you for decades…

I started working with watercolors in 1971 and have never stopped. I have always drawn in pencil and with an ink pen, but fifty years ago, I added watercolor. Initially, I looked at this technique while illustrating books for children. I made many such books, many of which have been published in many countries. In parallel, I started making watercolors for myself.

One immediately notices your mastery and familiarity with the medium, which allows you great freedom. When one first looks at them, one is aware of looking at a watercolor, then they gradually take on corporality, which makes one forget the medium and see the art.

Watercolor can still surprise you like anything that hasn’t run out of possibilities. I remember in 1960, Armin Hary, a German athlete, won the 100 meters at the Rome Olympics in 10 seconds flat. Sixty-two years later, they gnawed another 15 hundredths of a second. This happened because the techniques, the materials, and the shoes themselves allowed this slight performance improvement. Similarly, the watercolor technique can constantly improve.

I know you also work in oil; what specifically continues to attract you to watercolors?

Oil paint and tempera allow one to cover up, to paint over it when one is not satisfied. Tempera can be corrected; watercolor is not correctable. At most, you can change it. You have to accept what happened. And this is a great challenge.

The watercolor is very restrictive, but I find a sense of freedom in the restriction.

I am struck by the apparent simplicity of your watercolors.

The difference between elementary and simple is like the distance between A and Z. Elementary. can be the materials: A, B, C, etc. simplicity is using the medium (watercolor and paper) to its fullest potential, and that is the direction toward which I strive.

Often, the works in series have something formulaic about them. However, here, each landscape seems to add something to the previous one. Similarities and diversity invite a more attentive, reflective look.

I always try to aim for “the rightness”, the right measure. Especially in this exhibition where the horizons are all flat, the light — as happens in the real world— is what makes a day or a season different from the other. Our gaze, our life, risks becoming frighteningly monotonous: it is the light that transforms every moment into something different. A light change (often corresponding to a change in mood) arouses the desire to live, discover, and move forward in us. I am searching for a balance where light, measure, and proportion, combine.

This exhibition has overturned my belief that an event like the Covid-19 pandemic needs time before becoming material for artistic elaboration. On a table in the second room of the gallery, there is an album of yours, which deals with another watershed event: the attacks of September 11th 2001 …

It is a collaboration with Serge Gavronsky, an extraordinary person, a great poet, who taught for years at Columbia and Barnard, we had often talked about looking for an opportunity to collaborate, but it just did not happen until now.

When the twin towers collapsed following the terrorist attack, I was in Italy but returned to New York a month later. As soon as I could, I went to visit a friend, an English painter, who lives just south of where the two towers stood. From his place, I was allowed to pass the barriers and reach Ground Zero. The album you saw is a sequence of 20 “invented images,” reinterpretations I created last year, thinking of the devastation I witnessed shortly after 9/11.

I know that you have often “collaborated” with poets…

Yes, I have had significant exchanges with various poets. Among others, Andrea Zanzotto, Luciano Erba, and in America with Robert Bly. Last year, twenty years after 9/11, I proposed a collaboration to Serge. He accepted by combining my images with poems with the same theme he had composed in 2002. So the album has 20 of my watercolors of 2021 accompanied by the handwritten transcription of his poems.

You are in New York after the pandemic, and you came here after 9/11; what has continued to attract you to this city since 1981?

I don’t know the new Asian metropolises, but New York has unique characteristics among the big cities I know. Some cities meet the needs of markets, and others, the needs of man. With New York, I have had my ups and downs, I sometimes wondered if this is the best place for me, but these doubts have been overshadowed the frequency of small epiphanies that I have had and continue to have when I am here. New York is, in some ways, a unique place where the individual has the opportunity — sometimes is forced— to confront other individuals. This for me is the great attraction. It often pondered on the fact that only two decades after the founding of this city, in the first half of the 1600s, twenty different languages were already spoken here. For some reason, this has always been more than a city: it is a place of international encounters.