For the last three years I have been immersed in opera for my forthcoming book, Two Against Hitler: The Daring Mission to Save Europe’s Opera Stars from the Nazis. And among the most interesting characters I have come across is the legendary Italian-American basso Ezio Pinza.

Born in Rome in 1892, he rose from poverty to become one of the world’s biggest stars of both the stage and screen. But his life story is tinged with tabloid intrigue and tragedy, and could itself have been its own opera.

Fortunato Ezio Pinza was his parents’ seventh child, but only the first to survive infancy. It was Pinza’s father who first noticed the beauty of his voice, and encouraged him to study opera. Pinza had other plans, and became a professional cyclist at 18. Although he won no distinction in the sport and quit after two years, he credited biking for developing his prodigious lung capacity, allowing audiences “to hear my voice even in the top of the peanut gallery.”

But his operatic studies were fraught with their own challenges, not the least of which was his initial rejection by a teacher at the Rossini Conservatory who said he had no voice, and the sudden death of a second. He eventually returned to the teacher who had formerly rejected him, and this time was able to secure a small scholarship which he supplemented by working as a handyman. He made his singing debut with a small opera company outside Milan in 1914, and when war broke out, he enlisted in the Italian army. After the war, he tried to resume his fledgling opera career, and his lucky break came when he entered the company of Milan’s La Scala under the baton of Arturo Toscanini. After three years with the storied company, Pinza was discovered by the Met’s Giulio Gatti-Casazza. He made his debut in New York in November, 1926.

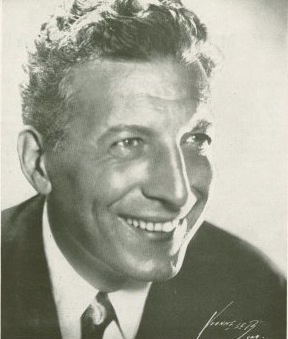

A critic hailed Pinza as “a majestic figure on the stage [and] a basso of superb sonority.” He was also a serial womanizer, true to one of his most famous roles, “Don Giovanni,” Mozart’s notorious playboy who forges the path of his own destruction.

With his slicked-back wavy black hair and signature fedora, Pinza was a dashing star who carried on affairs with some of the most celebrated opera divas of the 1930s and 1940s. Rosa Ponselle called him a lecherous “pig” who made an effort to seduce as many women as possible. His long-term liaison with German diva Elisabeth Rethberg led his wife Augusta Cassinelli to sue the dramatic soprano for $250,000 in 1935, blaming Rethberg for the “alienation” of her husband’s affections in New York State Supreme Court. The lawsuit was front page news in the “New York Times” at a time when Pinza was preparing for the Met’s “Faust,” playing Mephistopheles opposite Rethberg, who played the role of the maiden Marguerite in the opera. The suit was eventually dropped, although Pinza and Cassinelli divorced.

Years later, a tryst with Gretel Walter, the daughter of Bruno Walter, who had conducted him in “Don Giovanni” at the Salzburg Festival, turned tragic. Weeks before the beginning of the Second World War, Gretel’s husband found out about the affair and shot her to death in a jealous rage, turning the gun on himself.

Life seemed to settle down after Pinza married an American woman and settled in the Westchester suburbs with their infant daughter in the early 1940s. But in March 13, 1942, two FBI agents barged into Pinza’s Mamaroneck home through an open door and arrested him “in the name of the President of the United States.” Pinza was hauled off to an internment camp on Ellis Island, one of tens of thousands of “enemy aliens” locked up by federal authorities months after the US entered the Second World War.

The news of the internment of New York City’s biggest opera star, who was four months shy of obtaining his US citizenship, was front page news the following day. Authorities said Pinza had been on friendly terms with Italian dictator Benito Mussolini.

“The charge that he has been friendly with Mussolini is perfectly ridiculous,” said Pinza’s wife Doris Neal Leak in a statement shortly after his arrest. “He never even met Mussolini and furthermore, in 1940, turned down an invitation to participate in the May Festival in Florence, Italy, because he wishes to remain in the United States.”

According to his granddaughter, Sarah Goodyear, who wrote about Pinza’s arrest and internment decades later, “he was not told the substance of the charges against him.” Nor was he allowed an attorney. He spent 11 weeks in prison, and was released only after fervent pleas from Nobel laureate Thomas Mann and New York Italian anti-Fascist journalist and labor organizer Carlo Tresca. Pinza was finally allowed to leave his Ellis Island prison on the condition that he report weekly to “a reliable US citizen.” In this case, it was his physician.

Pinza’s imprisonment when he was 50 years old and at the apex of his career haunted him for the rest of his life. Although Pinza logged in 750 performances in 50 operas at the Met and even had a career on the Broadway stage and in Hollywood, his imprisonment ruined his health “and led to severe bouts of depression,” Goodyear wrote.

On May 9, 1957, Pinza died of a stroke, shortly after completing his memoirs which were published a year later.