If you are a fan of the “Commissario Montalbano” (Inspector Montalbano) films made for Italian television, you are a fan of Salvatore De Mola. The fifty-one-year-old screenwriter from Bari has written nearly 30 episodes of the popular RaiUno series based on the novels by the late Sicilian author Andrea Camilleri. He has also written four episodes of “Il giovane Montalbano” (Young Montalbano), a prequel to the main series focusing on the detective Salvo Montalbano’s early career. (Both series are available to English-speaking viewers, in the United States through the streaming service MHz, and in Great Britain on the BBC.)

De Mola’s other television credits include some of the most popular and highly praised series and features of the past 20 years: “Francesco” (2002), “L’isola di Pietro” (Peter’s Island, 2017), “Nel Nome Del Male” (In the Name of Evil, 2009), and “Storia di Nilde” (Nilde’s Story, 2019), a biopic about Nilde Iotti, a Communist, a member of the committee that drafted Italy’s postwar constitution, and the first woman president of the Chamber of Deputies (2019, RaiUno).

But De Mola doesn’t write only for television. His screenplay for the film La Stoffa dei Sogni (The Stuff of Dreams) won the David di Donatello 2017 (Italy’s equivalent to the Academy Awards) for the Best Adapted Screenplay and received the Best Film award at the 2017 Italian Golden Globes.

His other film credits include Fango e Gloria (Mud and Glory, 2014), winner of a special Nastro d’Argento award and a nominee for Best Film at the 2015 Italian Golden Globes; Cento metri dal paradiso (One Hundred Meters From Paradise, 2012), nominated for a Nastro d’argento for Best Story.

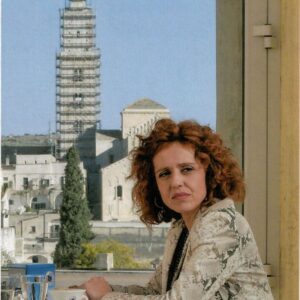

As this list of just some of the highlights of De Mola’s career indicates, he is hardworking and prolific. His script for This is a Man, a new film directed by Marco Turco and starring the actor Thomas Trabacchi as the writer and Holocaust survivor Primo Levi, is being shot in Italy. He is also the head writer on “Imma Tataranni Sostituto Procuratore” (Imma Tataranni: Deputy Prosecutor), a hit series set in Matera that debuted on the RaiUno network in 2019. (Its first season is available on Mhz.) Imma, played with passion and intelligence by Vanessa Scalera, juggles her professional life with a sexist boss and a handsome young cop who is infatuated with her (and she with him); and her home life, with a devoted husband, a sullen teenage daughter, and a cold, disapproving mother-in-law. De Mola is currently writing the scripts for the series’ second season.

In August, I interviewed De Mola (via email) about his current projects, how he became a screenwriter, the crime drama genre, and a few other topics. He also had a few things to say about the future of the “Commissario Montalbano” series. What follows is a translated and edited version of our conversation.

Why did you want to write a film about Primo Levi? And is it about his life before or after Auschwitz?

Actually, a producer proposed it to me. But then I felt that I wanted to do it, that it was necessary to write about Primo Levi and his experience. I would never have imagined that there would still be a need to let young people know that there was the Holocaust. But unfortunately, there is a need, because it seems that fascism is coming back into fashion. But I didn’t want to do the usual “saintly” biopic. And on the other hand, I can’t do things that don’t have an element of novelty; otherwise, I get bored. So, I started from one of the things that struck me most about Levi: the fact that Auschwitz was a sort of sliding door for him, which led him not only to want to be a writer but also and above all, another person.

He was not a practicing Jew, but after the deportation, he began to take an interest in Judaism. He wanted to be a chemist and became a writer to keep alive the memory of what he had lived through. But he continued to be a chemist all his life. In short, the character of Levi is very rich and multi-faceted, and “born” from the lager. So, I imagined what would happen if he didn’t end up in that camp. What would his life have been like? Would he have been more or less happy? Because what emerges from the study of Levi’s biography is that he was a very unhappy man. There is not much clarity about his end either: he probably committed suicide by jumping from the stairwell of his apartment building, where he was born and spent his whole life, with the parenthesis of the lager. But why? Suicide is a fate shared by many Holocaust survivors, but in Levi’s case everything is more complicated by the writer’s inner life. Compared to the film about Nilde Iotti, this one is a bit more ambitious from a formal point of view, less realistic and more oneiric.

Let’s talk about the series, “Imma Tataranni”. It is based on the novels by Mariolina Venezia, and stars Vanessa Scalera as Imma. There are four books, but there were six episodes in the TV series’ first season, and you are writing the second season. There are fewer books to adapt than with Montalbano, thus less material. How much of the series is original, written by you and your team?

We worked with the writer [Venezia] on the “bible,” the canvas on which to build the series. Of the six episodes of the first season, three were adaptations of novels and three original subjects developed by me, Luca Vendruscolo, and Venezia. For the second season, which for now will consist of eight episodes, one will be taken from a novel and the other seven from new material. The writer is working on the ideas, and then we scriptwriters will adapt them.

Paradoxically, I like it more when I can work on characters than when I have to adapt a novel. There’s more freedom, even if you have to move in the wake of characters created by others. That’s why I prefer adaptations to stories written from scratch.

“Imma” at times seems like a feminist “Commissario Montalbano.” Besides Imma herself, the show has other strong women characters, including two who work with her in the prosecutor’s office. Was there a conscious decision to make the series feminist or woman-centric?

Well, Venezia’s novels are very strong in that respect. We tried, although we are all males in the writers’ room, to preserve the original spirit. We hope we’ve succeeded.

The character of Imma is fascinating and complex. She is highly intelligent, with an exceptional memory, and very good at her job. Yet, emotionally, she seems stuck in adolescence; she has had no sexual experiences other than with her husband, and she has become infatuated with Ippazio Calogiuri (Alessio Lapice), a handsome young policeman. She behaves almost like a teenager when she is with him. In one episode, she explains that when she was young, all she did was study because her mother sacrificed so that she could study, and she had no sexual or romantic life, unlike her peers.

This is one of the elements of the character that I like the most, perhaps because it reveals an autobiographical part of myself. I too, like Imma, come from a family with few means. My father worked in a billiard factory, but for a relatively long time, he occupied [squatted in] his factory. Then he set up a cooperative with his colleagues, which went badly, maybe because, in the 1980s, no one wanted to spend a lot of money on billiard tables. My mother was a seamstress, and I learned from her the precision of details and the need, sometimes, to tear it all up and redo it. So, at some point, like Imma, I realized I had to get busy, study, and work. Like Imma, I’m the first graduate of my family. So, first university and a degree in Literature, then a job in a publishing house and then, at thirty, my life’s choice: to be a screenwriter. I left Bari, my city, and came to Rome: Hollywood on the Tiber. But Imma, yes, she’s stuck in adolescence. That’s why she has difficulty with her daughter—who is a teenager—and she can’t manage her crush on Calogiuri as a mature woman would.

In “I giardini della memoria,” the third episode of “Imma,” homosexuality, the condition of gay people, and gay rights are essential to the story. I thought the screenplay dealt with these issues very well, with intelligence and sensitivity. For me, this is unusual for Italian television.

I’m not too fond of the way Italian series sometimes portray homosexuality, with rare exceptions—the series “La compagnia del Cigno” and “Tutti pazzi per amore” created by Monica Rametta and Ivan Cotroneo, for example. What you mention is an original episode, and I’m particularly happy with how it came about: we wanted to tell without fear, and without rhetoric how there are many problems in trying to live one’s sexuality in a southern Italian city. When we were researching [the episode] with people in Matera, they told us: “No, there are no homosexuals in Matera!” A bit like how they used to say that the Mafia didn’t exist in Sicily!

The series has a powerful sense of place, with very evocative scenes of Matera. How important is place for the series? In the Montalbano films, one is always aware that they are set in Sicily. Matera and Basilicata seem as central to “Imma.”

One thing that not only Montalbano but also other great international series have taught us is that the more you show a precise, identifiable place, the more universal you can be, the more you can touch a vast audience that goes beyond national borders. I often vacation in Sicily, in the area where the series is shot. There are road signs indicating “Vigata,” which, as you know, is an imaginary place. And there many people who go there from all over the world to find the Montalbano locales. The difference with the location of “Imma” is that it’s Matera, not a mix of towns and villages in the Val di Noto and Ragusa [in Sicily] that “become” Vigata. In adapting the novels of Venezia, we wanted to capture the authenticity and universality of those characters, who are like that because they live in a place like that, which has oil wells but seems to have stopped thirty years ago, where, for example, there is no train station. You can only get there by bus.

In the United States, since the Black Lives Matter movement, there has been discussion of the crime story genre or police procedurals; the argument is that they are “copaganda” because they are usually written from the point of view of the police or are at least sympathetic to the police. And yet we know that police, in the United States and in Italy, mistreat people, and especially powerless people and black people. In one of the Montalbano novels, Camilleri has Salvo express his [Camilleri’s] anger at police brutality at the Diaz school in Genoa.

I’ve been wondering a lot about that too, in recent months but even before. As you know, much of my production, especially television, belongs to the crime genre. It’s a genre that I like because it allows you to address reality while also confronting social problems, but in a compelling way and by creating a strong empathy with the viewer. A predisposition that comes from my passion for the film noir of the 1940s-50s-60s and the new Hollywood—”Chinatown” and “The Godfather” with “Goodfellas” and “Casino” my points of reference up to what I consider a masterpiece of the genre, “The Wire” by David Simon.

Keep in mind that we too have had a “George Floyd”: Stefano Cucchi, killed by the brutality of a group of carabinieri who for years were protected by other ranks. And, recently, the criminal actions of a Carabinieri barracks near Piacenza came to light.

One of the most beautiful films in the history of cinema, in my opinion, is Elio Petri’s “Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion,” starring Gian Maria Volontè, from 1970. And one of the most obnoxious characters in “The Godfather” is Sergeant McCluskey. When Michael shoots him in the head, applause breaks out in the theater. Think also of Orson Welles’ “Touch of Evil”. Can “serve and protect” permit the suspension, even if partial, of civil rights? My position, after years of profound and painful reflection, is precisely the one described by Camilleri that you mentioned: there are “rotten apples,” perhaps even part of the system is profoundly corrupt, but we can’t forget that there are many, among the police, the carabinieri, who do their job well and are important for the community.

You said in another interview that you think American television series have set a standard, shows like “Breaking Bad”, “The Sopranos”, “Mad Men”. I interpreted it as if you said that American TV is superior to Italian TV. True?

It’s a little more complicated. Let’s say I want to do a show like “The Wire.” I write some powerful episodes and, by a miracle, an Italian network, not satellite or on demand, let’s say Rai or Mediaset, buys the show. It’s a cop show, so we need police cars, uniforms, props. The production can’t afford to spend so much money on these things—compared to American budgets, ours are much lower. So, you go to the media relations offices of the police or carabinieri and ask to use vehicles and uniforms. They will want to read the scripts. And there is something that looks a lot like censorship, in the sense that they don’t force you to change but they tell you that they won’t give you the facilities. And that’s why sometimes Italian series become “copaganda.” Obviously, there are exceptions: think of “Gomorrah” or, in general, the series on Netflix or Sky. In short, I don’t think there’s a “creative” difference between the two sides of the Atlantic—even if it’s true that the shows you mentioned have deeply changed our way of thinking about a series. On the contrary, I believe that our tradition can make a great contribution to the innovation of a narrative form that is continually developing.

How has the pandemic affected film and television production in Italy?

I have been working, fortunately, because I have the second season of “Imma” to write. But it was postponed, as was another series that I wrote, adapted from the novels of a Sicilian author, Gaetano Savatteri. This series began a few weeks ago, in Sicily, with a stringent protocol to keep any contagion on the set under control. Actors and technicians are continuously monitored; they do tests every day. Obviously, costs go up, and it becomes extremely complicated to work overtime. Everything becomes more rigid and less elastic. But slowly the industry is starting up again. Unfortunately, a lot of cinemas are still closed. But this, to tell you the truth, I don’t see as a big problem: of course, I’m sorry that theatres, at least in Italy, are in crisis – and they were already in crisis before the pandemic. But I’m glad that, during the long months of lockdown, many Italians have discovered TV series, especially the most original and innovative ones

Tell us a little about your experience of writing the Commissario Montalbano series, and its future.

For me, the experience of the “Montalbano” writer’s room was fundamental. Practically everything I know I’ve learned in almost twenty years of working on that series. They were beautiful, exciting years, in which I had the opportunity to work within the perfect organizational machine of Palomar with great masters like [director] Alberto Sironi and Francesco Bruni. And I would also like to mention Gianluca Tavarelli, the director of “Giovane Montalbano,” a prequel that does not make you miss the main series. I would like to continue to be part of this adventure, however the production proceeds, but I still don’t know what will happen.

Luca Zingaretti, who has played Salvo Montalbano since the Rai series went on air, recently said he doesn’t know if it will continue, and even if he wants to continue with it.

He knows more about the future of the series than I do, but I hope that it will still go on because people love the characters and his stories.