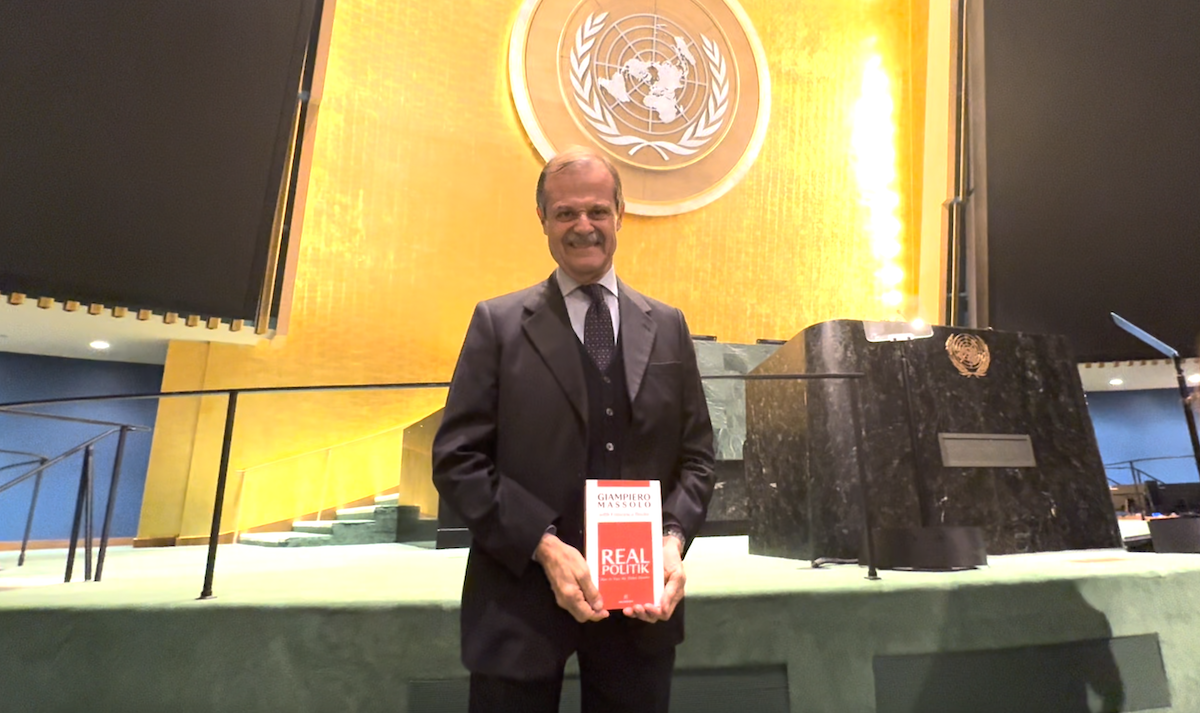

Ambassador Giampiero Massolo is in New York to present the English edition of his book Realpolitik – The Global Disorder and the Threats Facing Italy, co-authored with journalist Francesco Bechis. While in the city, he also took part in events at the United Nations Headquarters for “Change the World NYC,” the annual gathering organized by the Diplomatic Association. The conference brings together 3,500 students from over 130 countries as part of the “Change the World Model United Nations” initiative.

The former Secretary General of the Italian Foreign Ministry and former President of ISPI spoke to La Voce di New York the day after his participation in a student debate inside the UN General Assembly Hall, and shortly after he delivered a compelling lecture on the state of international relations to a packed room of young attendees at the Marriott Marquis in Times Square. Following the interview, Ambassador Massolo presented Realpolitik at the Consulate General of Italy on Park Avenue.

In this interview with La Voce, Ambassador Massolo—currently President of Mundys and formerly a strategic advisor to several Italian governments—offered a compass to help navigate the major geopolitical challenges facing Italy and Europe in the era of Donald Trump’s return. With clarity and intellectual rigor, Massolo urged us to view the world as it is, not as we wish it to be. Following the core message of his book, he reminded us that to understand the behavior of states—whether great powers or smaller nations—in today’s crises, we must recognize their immediate national interests. Only by doing so, he suggested, can we face the turbulence of the current global disorder with realism and, perhaps, greater awareness.

Stefano Vaccara: Ambassador, you just spoke to a group of young people, and this time, in just about fifteen minutes, you managed to condense an analysis of today’s global situation. While listening, one part especially struck me—when you said that in today’s world, people take risks. You were referring to investors, and you gave the example of someone walking into a warehouse packed with explosives, lighting a match—it doesn’t explode the first time, nor the second… but it could on the third.

Could you repeat that concept for our audience? I noticed the young people were listening to you very attentively.

Giampiero Massolo: We live in a very uncertain world, where crises overlap. These crises aren’t really solvable—at best, they can be mitigated to prevent escalation. No one truly controls all the variables: some don’t want to, others simply can’t. But what’s clear is that everyone—governments, markets, businesses—is increasingly inclined to take risks. There’s a normalization of risk.

Take the markets, for example: the effects of crises are now barely felt, unless the crisis is particularly dramatic. This happens because on one hand, there’s more willingness to take risks; on the other, there’s a belief that things won’t escalate to the extreme. Crises are managed not to solve them, but to contain them.

How long can this last? We don’t know. As you said, it’s like walking around with a lighter in a gasoline depot. But for now, this is how the international system is behaving. This risk-taking attitude is increasing. Let’s hope it stops here.

But given today’s global rivals—China, of course, but also rising powers like India and Brazil—this world that Trump envisions, one that’s peaceful but centered on national self-interest… is it really possible to achieve peace at any cost?

Massolo: We must always consider the cost of peace. The perspective changes when you’re the world’s most powerful country, like the United States, and you have a transactional president, someone who’s ready to put everything on the bargaining table. Trump, for instance, might try to weaken the bond between Moscow and Beijing by conceding something—possibly at Europe’s expense. A peace that’s too quick, one that doesn’t reflect the invaded party’s interests—Ukraine, in this case—could destabilize the entire continent.

So Europe, which cannot yet defend itself alone and won’t be able to for some time, needs to step up. Europe needs to invest in its own defense and in building an international political identity. This is a crucial moment—complex, challenging—and we’re approaching a U.S. presidency that is anything but predictable.

Speaking of Europe, there’s a meme going around online—it’s funny, but it makes you think. It says: over 500 million Europeans are asking 300 million Americans to protect them from 150 million Russians. If Europe were united, it would be a superpower. What are we missing?

Massolo: We’re not a state. At best, we’re a confederation. There has never been a clear identification of a common driving force among member states—no shared “European national interest.” When people speak of a “European interest,” they usually mean the lowest common denominator of national interests.

We have a huge market and a strong common currency—those are powerful tools. But political identity is something else. A common army would help, but that’s not realistic right now. However, there are at least three things we can do:

- Fully leverage existing treaties to enhance cooperation in defense and security.

- Use current tools to strengthen our industrial base and make the procurement system more cohesive and efficient—no need to change treaties, just better coordination.

- Involve the United Kingdom, given its military-industrial strength, and build coalitions of the willing—states capable and willing to carry out joint security and defense initiatives.

Let’s consider a hypothetical situation: the Italian Prime Minister finds themselves needing to make a decision that will either anger Europe or the United States. What advice would you give?

Massolo: I don’t think we’ll end up in a zero-sum situation like that. Strengthening Europe’s responsibility for its own security is exactly what the United States wants. They need to focus on their primary strategic rival—China—and can’t deal with multiple threats at once. If Europeans step up and manage European security, the U.S. can focus on Asia, knowing their flank is protected. That actually reinforces the transatlantic bond—it’s not in contradiction with a stronger Europe.

But Trump doesn’t like the EU as an economic bloc…

Massolo: True. Economically, it’ll be a battle of tariffs and negotiations—agreements made, broken, and remade. But geopolitically, if the U.S. wants to focus on China, they need a stable Europe. That requires two things: reducing Russian aggression and having a credible European deterrent.

To close on this topic—since your book is titled Realpolitik—some say a direct war between the U.S. and China is inevitable, just a matter of time. What do you think?

Massolo: China doesn’t accept a U.S.-led world order. It’s the only power both willing and able to challenge it, openly or not. And those in charge now are doing everything to prevent China from succeeding.

The terrain is mixed: cooperation and confrontation. Where cooperation helps contain Chinese ambitions, it’s pursued. When it doesn’t, then come tariffs, tech restrictions, and so on. This isn’t (yet) a military confrontation, and it probably won’t be—at least not in the short term.

There’s no Chinese interest right now in military conflict, not even over Taiwan. China plays the long game. Its economy is still struggling after COVID. By the way, democracies won the COVID war by opening up, not China by shutting down—and its aftereffects are still visible.

So for now, the battlefield is economic, technological, and financial. That’s where we’ll see the competition unfold. Down the line, we’ll see. But in this period, China will aim to consolidate its sphere of influence and show strength—especially in the South China Sea and around Taiwan—but the real clash is economic and strategic, not military.

Thank you, Ambassador, for providing us with this geopolitical compass. Let’s remind our audience that your book Realpolitik, co-authored with journalist Francenco Bechis, is now also available in English—making it accessible not only in Italy, but around the world.