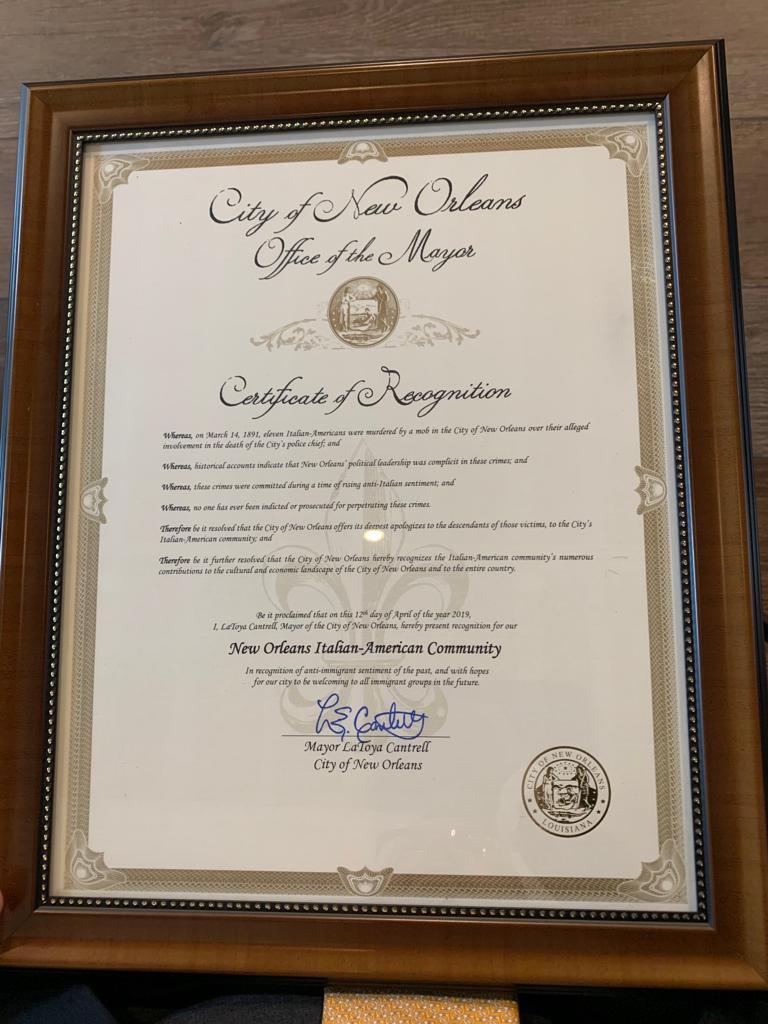

In a much-needed step in mitigating the pain of the discriminatory history against Italians in the United States, the City of New Orleans made an official Proclamation of Apology to Italian Americans on Friday April 12, 2019. This apology acknowledged the 1891 lynching of 11 Italian immigrants (eight of whom had American citizenship at the time they were killed) by an angry mob numbering in the thousands. In attendance at the ceremony held at the Italian Cultural Center of New Orleans, were the mayor LaToya Cantrell and the Italian Consul General for Houston Federico Ciattaglia. Italy’s Ambassador Armando Varricchio, expressed his gratitude from Washington DC to the Order Sons and Daughters of Italy for their dedicated efforts in bringing this about.

In a much-needed step in mitigating the pain of the discriminatory history against Italians in the United States, the City of New Orleans made an official Proclamation of Apology to Italian Americans on Friday April 12, 2019. This apology acknowledged the 1891 lynching of 11 Italian immigrants (eight of whom had American citizenship at the time they were killed) by an angry mob numbering in the thousands. In attendance at the ceremony held at the Italian Cultural Center of New Orleans, were the mayor LaToya Cantrell and the Italian Consul General for Houston Federico Ciattaglia. Italy’s Ambassador Armando Varricchio, expressed his gratitude from Washington DC to the Order Sons and Daughters of Italy for their dedicated efforts in bringing this about.

“This is a huge step in righting a wrong,” Executive Board Member of the Italian American One Voice Coalition Andre DiMino stated. “Sadly, this kind of treatment of Italian Americans was commonplace in New Orleans at the time – and we are happy to see the Crescent City step up to do what’s right.” It has become fashionable for government representatives to apologize for historical misdeeds, and certainly we have nothing against such gracious—though ineffective– gestures to redeem past brutality; the past cannot be changed. But frequently such gestures manage to obfuscate history rather than to clarify it. This infamous lynching has suffered such a fate. It is an understatement to say that the events that led up to it have been grossly oversimplified and some crucial facts have been obliterated altogether in the collective memory; indeed, even in some historical accounts.

The spark for the violence that claimed the lives of 11 Italian victims was the ambush and assassination of police chief David Hennessy. Immediately after the shooting a witness reported that when asked who had done this to him, Hennessey allegedly blamed “dagoes,” an anti-Italian slur, as the culprits of his death. As a result, hundreds of Italians were rounded up, and 11 were eventually tried. It is worth noting that Hennessey was greatly beloved in his city; his funeral was the largest held since that of Confederate President Jefferson Davis. “A band led the funeral procession to the cemetery, more than a mile long. The city’s fire stations rang their bells in requiem. Steamboats in the harbor flew their flags at half mast.”

Of the 11 alleged perpetrators put on trial, not one of them was convicted. A jury acquitted eight and couldn’t agree on guilt for the other three. This unexpected result greatly angered New Orleanians and on March 14, 1891, the public decided to take “justice” into its own hands. As various historical documents relate, some-8,000 New Orleanians stormed the Parish Prison where the newly-acquitted were being held. As one more example of the ambiguities of history, although many sources report that all 11 were lynched, not all agree. Some sources report that 2 were lynched and 9 were shot. Nevertheless, the popular belief is that this event is the largest lynching in United States’ history, complete with anti-Italian slurs and the mutilation of the bodies of the 11 victims.

Nor is there greater clarity as to the character of the “victims”. According to History.com, “these immigrants were hardworking and religious”. Yet a deeper look into the event suggests that this may not have been true for all of them. Salvatore Lupo writes in his book, The History of the Mafia, that New Orleans should be considered the birthplace of the Mafia in America. Indeed, it was the first American city to host a large population of Italians. And here is another of the surprising facts that are buried in history: after the Emancipation Proclamation of 1860 had freed the slaves whose labor had supported the American Southern economy, Italians—mostly Sicilians–were imported to work in the fields that now demanded paid labor.

This was a logical outcome considering that the US was importing massive quantities of citrus fruits from Palermo, Sicily. Between 1860 and 1900 New Orleans had the largest Italian community in North America. Not surprisingly, where there is commerce there is corruption, and the Mafia was making profit on both ends of the exchange: at the origin in Palermo where the fruit was shipped, and on landing in New Orleans. According to Vaccara’s thorough research in his book, Carlos Marcello, The Man Behind the JFK Assassination, Hennessey had become embroiled in the affairs of the Mafia, having favored one faction over the other in a dispute. Joseph Macheca, the noted Mafia capo officially listed as a fruit importer, was suspected of having put out a hit on Hennessey. Macheca was among those arrested and lynched. Another, Charles Matranga, survived the lynching by hiding in a trash can and continued to enjoy his position as a powerful Mafia capo. Clearly not all 11 victims were equally innocent or law-abiding.

Although Italians had been living in New Orleans since before the Louisiana Purchase, their language and customs were considered foreign and even dangerous by some. From their Catholicism to their unfamiliar food, to their close family relationships (seen as clannish and unpatriotic), Southern Italians and in particular, Sicilians, were viewed with a jaundiced eye. This connection to organized crime certainly did not help their public image, nor did it help them escape from knee-jerk discrimination and bigotry once the word “dago” was mentioned by Hennessey.

The Italian enclave of New Orleans was not an isolated one. As is widely known, the end of the 19th century saw an unprecedented number of immigrants reach the shores of the US. Not unlike the immigrant issue playing out today, these influxes of immigrants created a climate of widespread fear and suspicion of foreigners in general. And as happens today, the media also contributed to this panic, stoking the fears by inflating stories of their criminality and their boorishness. Politicians made use of such rhetoric for their own purposes. Indeed, Southern Italians were represented as being beyond the pale of civilized society.

In view of this general animosity against immigrants and some ethnicities in particular, it is not surprising that the mob was comprised of citizens from every class, including “future mayors and governors”, because it then becomes clear that, in 1891, the city was complicit in the attacks, allowing mob participants to evade trial and punishment for the crime.

Mayor Cantrell acknowledged this complicity, but it is doubtful that a lesson has been learned from the darker sides of history in the United States. We may not be lynching people today, but knee-jerk bigotry has not been wiped out and we witness cruelty against those that society deems to be undesirable on a daily basis. Justice is not “just” to all, and memories are hard to erase. Some New Orleanians of Italian heritage still remember facing the schoolyard taunt “who killa da chief?” as children. No apology can wipe that out. Mayor Cantrell rightly suggested that, “At this late date, we cannot give justice, but we can be intentional and deliberate about what we do going forward.”