It was a tourist’s – and resident’s – nightmare. In late June, ten people were shot on Bourbon Street in New Orleans, not far from two major attractions, Jackson Square and Pat O’Brien’s piano bar. One of the victims, a 21-year-old nursing student, died on July 2.

For New Orleanians who despise Bourbon Street, the shootings confirmed their view of it as tacky, dangerous, and even a blight on the city. The incident, according to news reports, was the third major shooting on the street in the last three years.

But Bourbon Street also is the city’s leading tourist attraction and entertainment district, where visitors can find something for virtually every taste – jazz clubs and strip joints, bars and souvenir shops, sleazy sex shows and fine dining. The street that many New Orleanians love to hate generates considerable tax revenue for an economically troubled city and state. The millions of annual visitors to New Orleans account for half of all state tax revenue from travel and tourism, and virtually all of those tourists will set foot on Bourbon Street, at least once.

Richard Campanella, Professor at Tulane University (Photo Paula Burch-Celentano)

Perhaps it took an outsider – albeit one who has lived in the city for some time – to explain Bourbon Street, to New Orleanians and to the world. Richard Campanella, born and raised in Brooklyn, is a professor of geography at Tulane University and the author of seven books about New Orleans, one of which, Bienville’s Dilemma, the New York Review of Books called “the single best history of the city.”

Campanella’s new book, Bourbon Street: A History (Louisiana State University Press), is a thoroughly researched, engagingly written, and altogether fascinating account of the mile-long street’s history, from the Louisiana Purchase to the present. I recently interviewed Campanella in New Orleans about the book, and particularly about the role of Sicilian immigrants and their descendants in creating Bourbon Street as an entertainment mecca. In the book, he writes, “Sicilians formed at least a plurality and usually a majority among Bourbon and [French] Quarter business and building owners, and more than any other group they deserve credit, or blame, for creating modern Bourbon Street.”

I asked Campanella whether it was true that the New Orleans mafia controlled Bourbon Street and its entertainment venues. “I wouldn’t use the word ‘controlled,'” he said. “‘Control’ sounds to me like 80, 90 percent: There are these machinations, they’re meeting in a room and calling all the shots.” Campanella describes the Mafia’s presence as “more a behind-the- scenes, influential consortium that coordinated a substantial amount of the really high-profit illegal activity. What is inside and what is outside the Mob? If you make a deal with one of these guys, does that make you an insider? Are you a mobster, then? Or are you just trying to keep your businessÔÇò’here’s 100 bucks, keep me safe.’ That’s why I’m very cautious about this.”

A view of Bourbon Street, New Orleans

“If you look at the extent of Bourbon Street, you have the thirteen blocks in the Quarter, one more block in Marigny. One-half is residential, another half is commercial, and there are a couple hundred businesses here. You’d have bars, some clubs, a restaurant, and something completely unrelated, like an electrical store. And in the backrooms of many bars and clubs, you might have a pinball machine that really was controlled by the mob. They paid off the bartender to make sure only they got the money. There were these bookmakers and poker machines, and illegal gambling. Meanwhile, a legitimate bar was up and running, and the bartenders might have nothing to do with the mobsters. But make no mistake, there were a number of owners who were out and out mobsters.”

“There’s a gradient, from a proper noun to a common noun,” Campanella said. “There’s Mafia, with a capital M, then there’s the mob, capital M, then there’s mob, then there’s mobsters, then there’s organized crime, then there’s all these affiliated parties. You’ve got be really careful about terminology.”

Campanella noted that Sicilians began to come to New Orleans in large numbers in the late 19th century, when “the state of Louisiana was working with the sugar planters to try to replace what had been the main labor source, slaves.”

“They tried [to recruit] Chinese for a while, Chinese from Cuba. They tried Scandinavians, Greeks, and Portuguese, they tried Spanish.” Campanella said that the planters didn’t find an alternative labor source “until they tried Sicilians, because in post-unification Sicily, there were a whole of reasons to get out. So now you have this place that’s recruiting you, what do you have to lose?”

Campanella says that the attempts to recruit Chinese as farm workers failed because the Chinese “urbanized within a year.” Many Sicilians who did not urbanize went into truck farming. “Sicilian families went from working on plantations to owning their own farms, raising high value produce, and bringing it in to sell in the markets in New Orleans, including the French Market,” Campanella said.

Urbanized Sicilians who had settled in the French Quarter (at one point, there were so many of them that the district was known as Little Palermo) began to move out in the 1930s and ’40s. “Throughout the twentieth century, there was this phenomenon of Sicilian-ness becoming an increasingly suburban, rather than urban presence. When I was doing research ten, fifteen years ago, I could find only a handful of Sicilian residents [in the French Quarter].”

After World War II, more Sicilians left for the suburbs, settling in towns like Kenner and Independence. “The local Sicilians were eagerly moving out to modern, middle-American circumstances,” Campanella said. “But as they moved out, oftentimes they held on to their properties, because they were aware that prices were going up. So today there is more Sicilian ownership of the French Quarter than there is Sicilian residency.”

When Sicilians arrived in New Orleans, they became a new flavor in the city’s ethnic gumbo – and an ambiguous category in the Southern city’s racial taxonomy. “Sicilians unknowingly moved into this post-Civil War environment,” Campanella observed, “and found themselves in a complex construction, and re-constructing of race, when Louisiana was polarizing its sense of racial identity, from the three-tier system it had in antebellum times, of free whites, free people of color, and enslaved blacks. This was one of the distinguishing elements of Louisiana society compared to the rest of the South.”

“After the Civil War, the very notion that there was this intermediate caste – free people of color, mostly but not exclusively black Creoles – became increasingly repulsive and threatening to the white caste. So the white caste redefined its identity and its past to the tune of the one-drop theory – if you had one drop of black blood, you were black. This hard line was drawn – artificially of course, but ‘artificial’ does not mean it did not have real impact – between whites and anyone with African blood. Then along came Sicilians into this toxic brew, and where did they fit in? Once Sicilians started to become aware of the caste system they found themselves in, they know damn well which category they want to be in.”

At first, many locals regarded the Sicilians as nonwhite, more akin to African Americans than Europeans. Whites and blacks both perceived Sicilians as friends and allies of blacks. The Journal of Negro History published an article about this era entitled The Italian, a Hindrance to White Solidarity, 1890-1898.

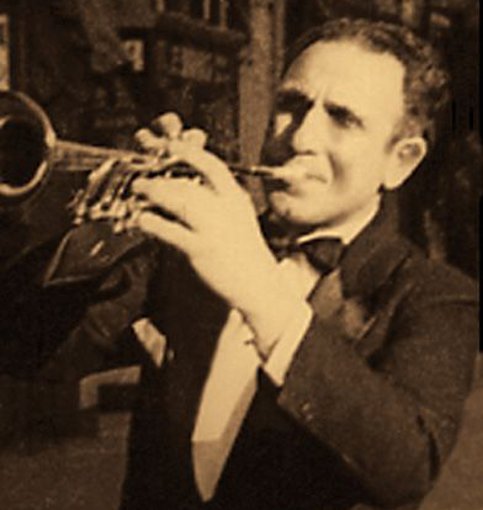

Nick La Rocca, famous jazz player from New Orleans whose family came from Sicily

Cosimo Matassa, the legendary recording studio owner and engineer who recorded most of New Orleans’ great African American rhythm and blues and rock and roll artists, recalls growing up in the French Quarter among Sicilians and African Americans, who lived “cheek-by-jowl.” Sicilians and African Americans shared cultural traditions, like St. Joseph’s Day celebrations, and an affinity for brass bands and music with strong rhythms. Sicilians, like blacks, even experienced bigotry and racist violence; there were lynchings of Sicilians in southern Louisiana, most notoriously the mob killing of 11 in New Orleans in 1891.

But as Campanella observed, Sicilians and their descendants came to see themselves, and act like, native whites. “Sure, there was plenty of door-to-door residential proximity among African Americans and Sicilians, and there were warm feelings. Most of these folks were poor to working class; they were unified a whole lot more by class than they were divided by race. But when it came to things like keeping Jim Crow and segregation in place, many in the Sicilian community found they could benefit more by hardening and reifying that sense of racism.”

“Take a look at some of the footage of the protests on November 14, 1960, the day New Orleans schools finally were integrated. Look at the whites protesting in the streets and you will recognize their faces. They are Italian faces, Sicilian, southern European, Mediterranean faces.”

A rally against desegregation in schools, New Orleans, 1960

Campanella noted that Sicilian American business owners on Bourbon Street were committed to maintaining the Jim Crow racial segregation laws, relenting only when racism “came with a bill, as when there were boycotts of conferences because of Jim Crow laws affecting hotels.”

“But it wasn’t only Sicilians,” Campanella added. “The owners of the Roosevelt Hotel, and The Royal Orleans, the first of the big modern hotels, built in 1960, all were upholding Jim Crow.”

Campanella suggested a thought experiment: “What would Bourbon Street look like today if it were not for the Sicilians? Let’s say that back in the 1870s, it had worked out with the Chinese, or they found some other alternative labor source, and there never really was a big Sicilian influx. New Orleans still would have been famous; it probably would have developed a modern tourism industry that sold its rambunctious past as a commodity. But would there have been this one street you went to? I suspect not. I suspect that while Sicilians did not create Bourbon Street per se, and certainly the Mafia did not create Bourbon Street, it would be very different without them.”

He noted that the Sicilian population in southern Louisiana is “an Americanized one.” “It has been here on average 100 to 120 years. As is often the case when you have an immigrant community that breaks off from the main population, sometimes they preserve cultural traits better than the motherland does. You see that here with French culture. Because Louisiana broke away from France well over 200 years ago, certain aspects of French culture are better preserved here than in France. With regard to Sicily, I’m told that the St. Joseph’s altar tradition is better preserved here than it is there.”

Campanella compares the New Orleans Sicilian history of immigration, struggle, and upward mobility to that of his own Italian American family, descendants of immigrants from Campania.

“Our American story is so archetypal, you could rip it out of a sixth-grade American history book and put our picture there and it would align perfectly with that general narrative. We are from around the Naples area, with ancestors who were fishermen, farmers, schoolteachers, and civil servants. But mostly rural. They originally settled in Little Italy, on Mulberry and Chrystie streets. By the early 1900s, they were living right off the boardwalk in Coney Island, and later settled in Bensonhurst –my father’s side. My mother was born on Hudson Street right outside the Brooklyn Navy Yard.”

“My father was an incredible man, a Renaissance man, truly brilliant,” Campanella warmly recalled. “He was a jack-of-all-trades and a master of many. He eventually got a four-year degree in electrical engineering from Polytechnic, which is now part of New York University, and a four-year degree in English literature from St. John’s University, in the ’50s and early ’60s. He taught for the Board of Education in high schools, back in the days when the city sent teachers to sick students’ houses –could you imagine this today?”

“My mother was born in poverty, my dad was not, but his parents were. Now my brother and I are both college professors, he’s at Cornell, I’m at Tulane. So there’s your Italian American story.”

Regarding his adopted city of New Orleans, where he has lived since 2000 (after eight years in Baton Rouge), Campanella said, “I have been fascinated with this city for forty-three of my forty-eight years, and I can trace it back to an exact moment. I was around five years old, and my parents were helping me read my first book, which was Meet Abraham Lincoln. The author talks about young Abe’s flatboat trip down the Mississippi River, down this long mysterious river to this exotic, mysterious city at the far end of it. And that planted the seed, the fascination in my little boy’s brain. I nurtured that for twenty years – ‘Wow, New Orleans, I don’t know too much about that place but I know it’s fascinating and someday I’m going to learn about it.”

Twenty years later, Campanella went to Louisiana State University, eighty miles from New Orleans, to do his graduate studies. He and his wife settled in Louisiana in 1992 and he began his New Orleans research. He has taught at Tulane University since 2000, and has written seven books. His previous book, Lincoln in New Orleans: The 1828–1831 Flatboat Voyages and Their Place in History won the 2010 Williams Prize for excellence in research and writing on Louisiana. Not too bad for an immigrant from Brooklyn.

For more information about Richard Campanella and his work, visit his website.