Professor Stanislao Pugliese, can we say that this is the largest academic conference on soccer ever organized in America? Or perhaps the world? To whom, other than you, does the credit go for organizing this extraordinary event?

Professor Stan Pugliese

While there have been other conferences on soccer in America and around the world, my colleague and co-director, Dr. Brenda Elsey confirms that it is indeed one of the largest conferences ever organized on soccer anywhere in the world. And she should know. She spoke at a FIFA conference devoted to the history of the World Cup last year in Zurich but it was not as large as our conference. Because she is recognized around the world as a major scholar of Latin American football, Dr. Elsey is responsible for inviting many of the foremost scholars from 20 countries. The conference is also organized by the Hofstra Cultural Center, who handles logistics, and the Office of University Public Relations.

The title of the conference is “Soccer as the Beautiful Game: Football’s Artistry, Identity and Politics.” Art, identity and politics. All these aspects of soccer are surely present in Europe, South and Central America, maybe in Africa, a bit in Asia . . . But not in the United States. Why?

I wouldn’t say that art, identity and politics don’t enter into American soccer; they are surely present, just not in the same way or the same extent as they are in Latin America or Europe. I am teaching a course on the history of soccer now and I am discovering that there is a long history of soccer in the US. And wherever there is history, there is art, politics and issues of identity. Who plays? Who pays? Who watches? What political, economic, and cultural forces make soccer different in America? These are I think interesting questions.

I wouldn’t say that art, identity and politics don’t enter into American soccer; they are surely present, just not in the same way or the same extent as they are in Latin America or Europe. I am teaching a course on the history of soccer now and I am discovering that there is a long history of soccer in the US. And wherever there is history, there is art, politics and issues of identity. Who plays? Who pays? Who watches? What political, economic, and cultural forces make soccer different in America? These are I think interesting questions.

The inventors of modern soccer were the English. Some say the Florentines of the Renaissance. But the Brazilians are always considered the best of all time, with or without Pelé. According to you, how much does the culture and the social history of a people influence the performance of national soccer team so that it might win a World Cup? Is it possible that the United States still doesn’t have the “culture” and the “history” to win a World Cup?

This is a complicated question. We don’t want to succumb to national stereotypes: the “orderly” Germans, the “chaotic” Italians, the “joyous” Brazilians; the “rugged” English. Yet if we accept the premise that soccer is a part of culture, then how could a nation’s culture not inform the soccer that it plays? For example: I have always felt that Italy is generally a conservative country. Does the style of catenaccio as developed years ago reflect the national character? I remember thinking that there were times when it seemed as though the Italian national team went on to the field thinking more “We can’t lose” rather than “We must win.” If you begin with that thought in mind, or a certain philosophy of the game, it is almost inevitable that you will play a certain way. Looking back as a historian, and I know this is heretical to say, but maybe it was OK that Italy lost I the final in 1970. What I mean is that if Italy had won that game, maybe that style of soccer that I don’t care for, would have dominated for another generation. Instead, playing the same way in 1974 got us nowhere and started the process that re-made Italian soccer into a different game, what it finally did become in 1978 and 1982 — a much more attractive and entertaining game. But we can read too much about national character into a single loss or victory. When Brazil lost the 1950 final to Uruguay, there were Brazilians who argued that Brazil was such a “backward” country that it would never in a World Cup! For more than a decade, the Brazilians have been playing more “disciplined” soccer and the Germans more entertaining soccer. Does this mean that their national character has changed? Perhaps.

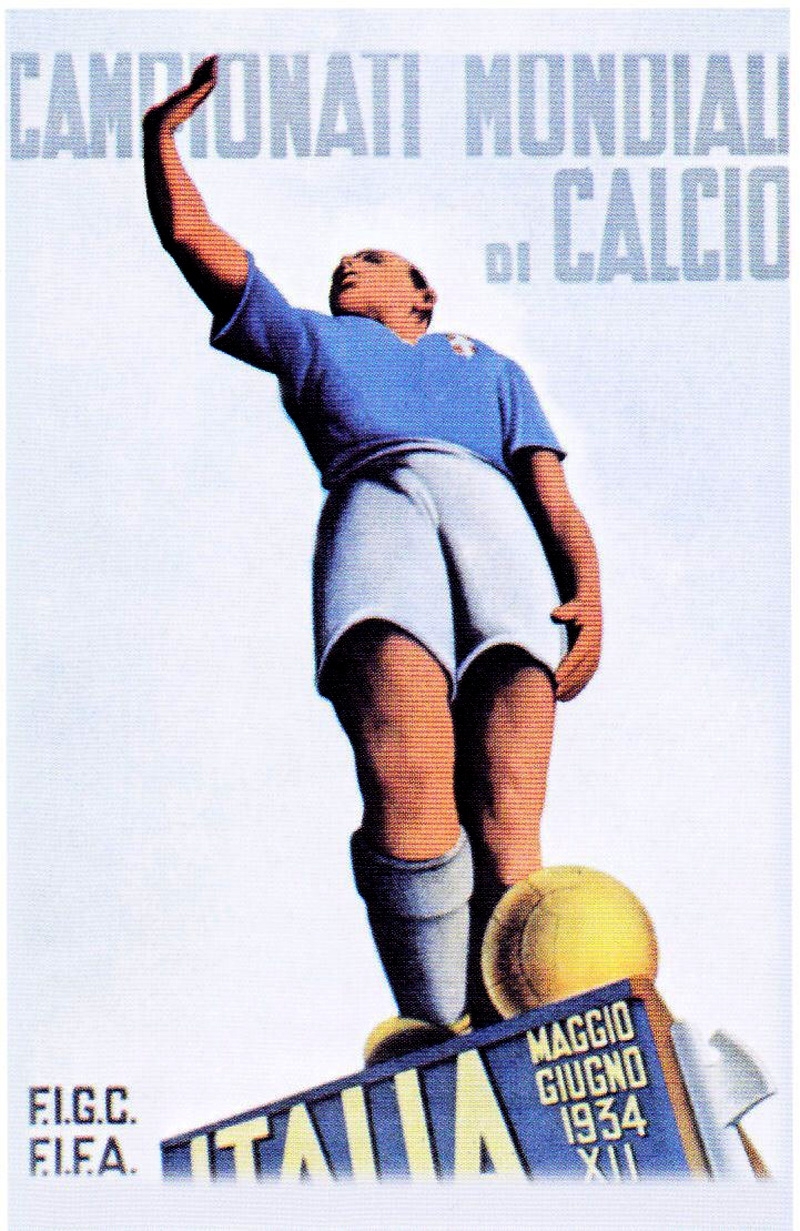

You are a historian, a specialist of the fascist period in Italy. Italy won its first two World Cups in 1934 and 1938. In your opinion is there a link between fascism and soccer? Was Mussolini the inventor of soccer as an instrument of propaganda and control of the masses?

Italy 1934: Fascist World Cup

If not the inventor, the one who took most advantage. Mussolini and the fascist regime were very conscious of the propaganda value of sport and did everything they could to make sure Italy would win the two World Cups. But this was part of a larger idea generated at the end of the 1800 and early 1900s that empires needed strong, healthy bodies. The gymnastic movement in Germany, even before the Nazi regime, was part of this history. In America and elsewhere, there was an unhealthy interest in eugenics. For fascism, Mussolini and the regime were young and vigorous compared to the declining sclerotic liberal democracies. Mussolini was often shown on horseback, on a motorcycle, skiing and while soccer wasn’t his sport, he fully supported the soccer teams in both World Cups. The teams, by the way, were obliged to salute in the fascist style on the field. And there was the influence of Futurism as well. We use Umberto Boccioni’s “Dynamism of a Soccer Player” (1913) as the back cover of the program. I would like to explore the relationship between Futurism’s ideas concerning modernity, speed, and dynamism with soccer.

But it wasn’t just fascism that hijacked soccer. In the 1950s and 1960s, the Soviet Union attempted a “scientific soccer” to follow their supposed “scientific socialism” and the inevitable, inescapable, iron laws of capitalism have produced a situation where a handful of tops teams owned by Russian oligarchs, Arab billionaires, and a (former) Italian prime minister dominate their leagues and international competition. Of course, this is all made possible by television and the billions it brings in.

Glancing at the more than 150 presentations of the conference, one sees that a major motif will be the influence of politics on soccer and vice versa. With soccer one can manipulate politics, one can influence public opinion, in short, one can maintain or lose social control, above all in those countries with high levels of poverty. Marx spoke of religion as the opiate of the people. If he had written Das Kapital in the 20th century, might he instead have said that it was soccer? Among all the many presentations, which do you think will be the most provocative?

Many leftwing intellectuals look down their nose at sport in general and soccer in particular. I too sometimes think that soccer functions as a soporific, both in the developed and under-developed world. Who knows what would happen if, instead of watching soccer all weekend, we talked about politics? There would probably be a revolution! So yes, sport and soccer may function to some extent like the pane et circensus of ancient Rome. But there is an important distinction: bread and circuses or the opiate of the people can work only of the people are not conscious of being manipulated. What if, on the other hand, we are conscious of the fact that the mass spectacle of soccer functions to protect the status quo?

Some speakers will address these issues and the unfortunate facts of corruption, betting, and the big business of soccer. One keynote speaker, Jennifer Doyle (University of California at Riverside) will argue for the abolition of the World Cup! I am eager to hear that presentation.

Italy goalkeeper Gigi Buffon with Pope Francis

Pope Francis is also a great fan of soccer. Will there be an examination of the relationship between religion and soccer? Is it the case that in certain countries soccer is now like a religion?

One speaker will talk about Papa Francesco’s team in Argentina. And yes, if you examine the fanaticism, loyalty, devotion of billions of fans across the world, soccer appears to have many of the attributes of a religion: sacred texts and sacred shrines, pilgrimages and martyrs, prophets, saints and heretics. At the most sublime level there is even perdition, damnation, redemption and salvation. There are glorious moments of transcendence. Is this a good or a bad thing? I would say rather that it is a fundamentally human thing.

The economic crisis in Italy has caused an explosion of protests anti-Euro and anti-Europe. People speak of secession and independence, there are demonstrations in the Veneto region, Sardinia, Sicily. Do you think that a victory in the World Cup in Brazil might resolve the ancient questions of identity or be the impetus to solve so many problems as the victory of Rossi, Tardelli and Zoff with President Pertini did in 1982?

Spain 1982: Italy’s Dino Zoff with the World Cup

I was 17 when we won in 1982 and I will never forget one of my heroes, the former partisan Sandro Pertini, at the final in Madrid. As much as that victory was welcome, I don’t think it solved any of Italy’s long-term, structural defects. 1982 could not prevent Tangentopli. I am sure the day after we won in Madrid, the politicians were again pocketing bribes. And we won in 2006 but still have the Lega and secessionists, racists, incompetence and corruption. But as important as these sport victories are (think of the military regime Argentina in 1978 or the West Germany’s victory in 1954 bringing it back into the family of Europe), I think they are short-term boosts rather than the solutions to problems. In fact, a defeat may change a country more than a victory. I am reading Pele’s latest book, “Why Soccer Matters” and in it he writes that Brazil’s infamous defeat at Maracana in 1950 actually worked to bring Brazilians together. A victory at the World Cup will not resolve the fundamental problems in Italy; in fact, a victory might just paper things over and make them worse. It’s like the thinking of the French generals after World War I: we won, therefore our strategy and tactics are better. Therefore we don’t have to change anything.

The conference celebrates Pelé, who for many soccer experts remains the greatest soccer player of all time. Do you think – and answer as a passionate fan not as a professor – he really was? If you asked this question of the Argentines and above the Neapolitans, as you know, they would answer Diego Armando Maradona.

I am a Napoli fan and therefore eternally indebted to Maradona for the two scudetti he brought to Naples. I am writing a book about Naples now and I will argue that Maradona was really a late-twentieth century scugnizzo. But that doesn’t mean that I can’t recognize Pele’ as the greatest soccer player ever. Once, when my young son Alessandro and I were watching a game (he is a Juventus fan), he asked which team I wanted to win. I told him: “Whoever plays better,” and I realized it confused him a bit. Soccer demands partisanship but I often feel like the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano who once said “I go about the world’s stadium with an outstretched hand like a beggar and plead: “A beautiful move for the love of God!”

You grew up in the tri-state area? Were you perhaps one of those children who went to see Pelé play with the NY Cosmos? Was it Pelé, Chinaglia and Beckenbauer who ignited your passion for soccer?

Cosmos’ 70s Stars Giorgio Chinaglia and Pelé

Yes, I grew up on Long Island and was passionate about the Cosmos, not just Pele but all of them. I spent many nights listening to games on the radio while my family was asleep and was in the stadium the night Chinaglia scored 7 goals. It was a fundamental part of my (misspent?) youth. But not just the Cosmos: soccer in general was a way to identify myself as “Italian” and distinct from my “American” brother who played baseball. I didn’t want to assimilate and soccer was a perverse “badge of honor” at a time when the popular sports in high school were baseball, basketball and football.

Will you and your children root for the United States or Italy? This summer the World Cup is in Brazil. After this academic conference, perhaps you will go there to see the games with Pelé?

While I admire the American team, there is no debate or dissention: in our house we are all fans of Italia. (I am just as excited when my son Alessandro and my daughter Giulia are playing as when gli Azzurri play.) It is a choice, an elective affinity, a way for me and my children to try to keep alive a filo to Italy (where we vacation every year.) It’s a way for the children of immigrants to maintain ties to the mother country and also perhaps assuage some guilt at having left. But you must accept the pain along with the joy. It was painful to watch Italy lose to Spain in the 2012 Euro final. After the 2006 World Cup I wrote an essay “On Soccer and Suffering” to remind myself that for every victory, there are sometimes many defeats.

As far as Brazil is concerned: if, after the conference Pele invites me, I will be happy to go!