Two nights every week, small throngs of New-Yorkers-in-the-know crowd an unmarked staircase leading to the second floor of a Mexican restaurant on 54th Street, seeking not just to go one flight up, but also to go eighty years back in time.

They arrive at a usually-packed night club setting from another era. Up on the stand is an 11-piece band in tuxedos, the players standing for solos or section ensembles, just as in an earlier time, and dominated from the back row by a big-boned, square-jawed handsome whirlwind of energy named Giordano, who is surrounded by his bass, his tuba, and his (fairly rare) bass saxophone. As he counts off the next tune, the 20s and 30s of American jazz spring back to life.

Employment for jazz musicians in those decades (plus a little before and after) was dominated by the big band. Even Louis Armstrong, whose most familiar recordings are with small groups, from the Hot Five to the much later All-Stars, actually played most of this part of his career either in, or fronting, big bands.

Louis Armstrong

The small ensemble recordings were special studio dates, not his regular work. His bands, and dozens of others, spent most of every year on tour, moving from city to city for one-or-two-night stands in the Cincinnatis, Seattles, and Denvers of America. They usually played in large ballrooms and they travelled by bus. You could judge how well a band was doing by whether or not one of the musicians had to drive the bus. The road, especially in the days when bands that were a mix of black and white musicians had regular trouble with hotel accommodations, was hard, but the musicianship was often excellent.

If a ballroom or night club had one or two “big name” bands during the week, some of the other nights were filled in with “regional bands”, local orchestras, often very popular, that found work closer to home. Every city of any size had them. And both these cities, and the radio stations and networks, had many hours of live music throughout the week, sometimes remote broadcasts from jazz clubs, sometimes playing in the radio studios. It all added up to a large population of regularly-employed musicians.

No more. There were several reasons for the rather rapid decline and death of big bands, many of them obvious. The post-war movement to the suburbs removed from city life many of the people with enough money to go out at night. Increasingly-attractive television programming kept a large part of America nailed to its sofas. Younger people, the next generations of audience, were losing interest in dancing, and in melody, and would soon turn, via “rhythm-and-blues”, to tuneless predecessors of hip-hop and rap. But a key figure in making big bands a vanishing species was another Italian-American, a labor leader named James C. Petrillo.

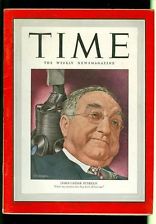

The son of an Italian-born sewer digger, Petrillo grew up in Chicago and quit school after it took him nine years to get through the fourth grade. Petrillo played trumpet, but his great talent was for organizing workers. He became the head of the American Federation of Musicians in 1940, and ruled the union with an iron fist, brooking no dissent until eventually voted out of office. His fame came first from a strike of recording studios that lasted most of two years right in the middle of World War II. The ban on recordings even angered President Roosevelt, who felt that music was important to war-time morale.  It landed Petrillo on the cover of Time Magazine, but most musicians who, according to the musicians’ blog AllMusic, “heartily disliked” Petrillo, felt that the damage done to big bands by the war-time ban, and two more strikes called by Petrillo after the war, was irreversible. Petrillo was, quite properly, seeking to improve the payments to musicians, especially for studio work. But he refused to credit clear evidence that the main employers of musicians were being pushed over the tipping point, beyond their ability to pay.

It landed Petrillo on the cover of Time Magazine, but most musicians who, according to the musicians’ blog AllMusic, “heartily disliked” Petrillo, felt that the damage done to big bands by the war-time ban, and two more strikes called by Petrillo after the war, was irreversible. Petrillo was, quite properly, seeking to improve the payments to musicians, especially for studio work. But he refused to credit clear evidence that the main employers of musicians were being pushed over the tipping point, beyond their ability to pay.

By the early 50s live music, once a staple, had almost disappeared from both radio networks and local stations. As an example, KVI in Seattle, which had aired five daily programs with live musicians, and was only one of four stations in town to do so, could no longer afford any such broadcasts and had, by 1952, turned the air waves over to that new phenomenon, the disc jockey.Even the great NBC Symphony was a luxury the network could no longer afford.

Unusual among American labor leaders, Petrillo was never accused of corruption or dishonesty. But his tactical blunders were historic. In going for too many golden eggs, he killed the goose.

So the regional bands were dying like flies in the early 50s, and even the big-name orchestras either folded or went part-time, touring only a couple of months out of the year. Count Basie and Duke Ellington hung on for a little while, but when the Basie band played the giant longshoreman’s union hall near Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco in 1959, the hall was packed for three nights, with only space for standing, not dancing or sitting, it was because the word was out that San Francisco would never see the Basie band again. That wasn’t quite true; the band popped up at festivals and on foreign tours through some of the 1960s. But even Basie’s musicians were having to find other jobs to supplement their income during the ever-increasing down time.

The Count Basie Band, 1940, Apollo Theatre, NY Harry ‘Sweets’ Edison (back row, 2nd from right). Photo by M. Smith from The Big Bands by George T. Simon

Thus the product of changing tastes, social geography, television, and James C. Petrillo’s strategic blunders was an overall decline in jobs for musicians, and absolute devastation for the form that featured big payrolls and expensive travel, and required an unbroken series of playing dates: the big band. The relics of this blighted landscape were the large ballrooms across the country. Some became auto dealerships or evangelical churches, but the spaces proved especially suitable for furniture stores.

The recordings were still there, of course, but during the great days of the big bands, the records, revolving at 78 revolutions per minute, could hold only three minutes and twenty seconds of music, sometimes a few seconds more, meaning the cutting of swinging repeats and, especially, of much of the space for the improvised solos by great jazzmen which were bands’ raison d’etre for many listeners. The discs are treasured, but they are archeological artifacts, like dinosaur bones.

Vince Giordano, Neapolitan-New Yorker from Brooklyn

But now…along comes a real live dinosaur, not a museum reconstruction, but a roaring, stomping, wailing, shouting, swinging big band, what the New York Times calls “an erupting wellspring of euphoria” that some time machine has, incredibly, deposited in the middle of Manhattan. It was not, actually, a time machine that performed this miracle, but a mezzo-napolitano from Brooklyn, Vince Giordano, the bandleader described at the beginning of this piece, who brings his band, the Nighthawks, into the Iguana on 54th Street every Monday and Tuesday night. Yes, it’s regular employment, undoing a little of what James C. Petrillo did when he helped throttle a great era of music. Because this band has no serious competition, it is also found everywhere from the Newport Jazz Festival to Lincoln Center, and won a Grammy for the music of the television series Boardwalk Empire. Giordano himself, as actor and musician, can be see in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Cotton Club and Woody Allen’s Sweet and Lowdown. On February 12, it will be the centerpiece for a Town Hall celebration of the 90th anniversary of the first performance of George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. All of those other jobs testify to the absolutely brilliant musicianship of the band, but it’s the steady job that floats it.

Jazz critic Phil Schaap says flatly that if Vince Giordano and the Nighthawks were actually playing in the 1920s and 30s, it would be one of the top bands in the land. And the injection of material from that era is constant. Giordano’s collection of 60,000 band arrangements of the period means that every night he adds new pages to the books of arrangements at each musician’s chair, already stacked up to the height of three New York telephone directories.

As the musicians scramble through these mountains of music to find the chart for the next tune that Giordano has announced, he kills the time by giving the audience a short course in the background of the music. So he has mentored many young musicians but also teaches all of us. What we’re really awaiting, though, is to hear him count off: “….and two….and three….and four” What happens next is bliss.